ANDY VAN DINH was born and raised in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, where he earned his BFA in Painting at the University of Calgary. He currently lives and works in New York City where he obtained his MFA from Hunter College. He has since gone on to exhibit at the Ada Slaight Gallery, Toronto, ON, SPRING/BREAK, New York, NY and Live at the Archway, Brooklyn, NY. I first saw Andy’s work while visiting his MFA program’s Open Studios event in 2016. I was immediately taken by the ethereal and symbolically rich nature of his work. His approach to drawing was so unique that in person it was difficult to tell what medium he was working in. I caught up with Andy at his home in Brooklyn where he’s riding out the pandemic. – Jessica Mensch

B O D Y: You’ve said that your work is autobiographical in the sense that it’s a place for reflection on your inherited trauma from war and colonialism. Where did you grow up?

Andy Van Dinh: I’m a first-generation Canadian and was raised in Calgary, Alberta for basically my entire life. Calgary is an oil and gas city, most famously known for The Calgary Stampede (an annual rodeo and festival), and the NHL hockey team called The Calgary Flames, none of which I could ever relate to. As a Vietnamese kid, if I tried to fit in by dressing up as a cowboy I would just stick out even more. As a kid it felt like a lose-lose situation. There is this almost false idea of the “West” that is portrayed in Calgary. No one is really a cowboy, and the city’s motifs feel like it leaves very little room for any representation of other types of people in Calgary. This “in-between” of a home and un-homed nation has resulted in an identity crisis for many minorities living in North America.

B O D Y: How did you inherit trauma?

Andy Van Dinh: The trauma came second hand from my parents stories of their time in Vietnam during the Vietnam war and their migration to Canada. Whenever I started to take things for granted they were quick to tell me a story from their upbringing. Their stories feel like they are very much a part of my story, as if it’s in my DNA.

B O D Y: You’ve spoken in the past about Stuart Hall’s idea of “imaginative rediscovery” in relation to your own creative process. Could you talk about this?

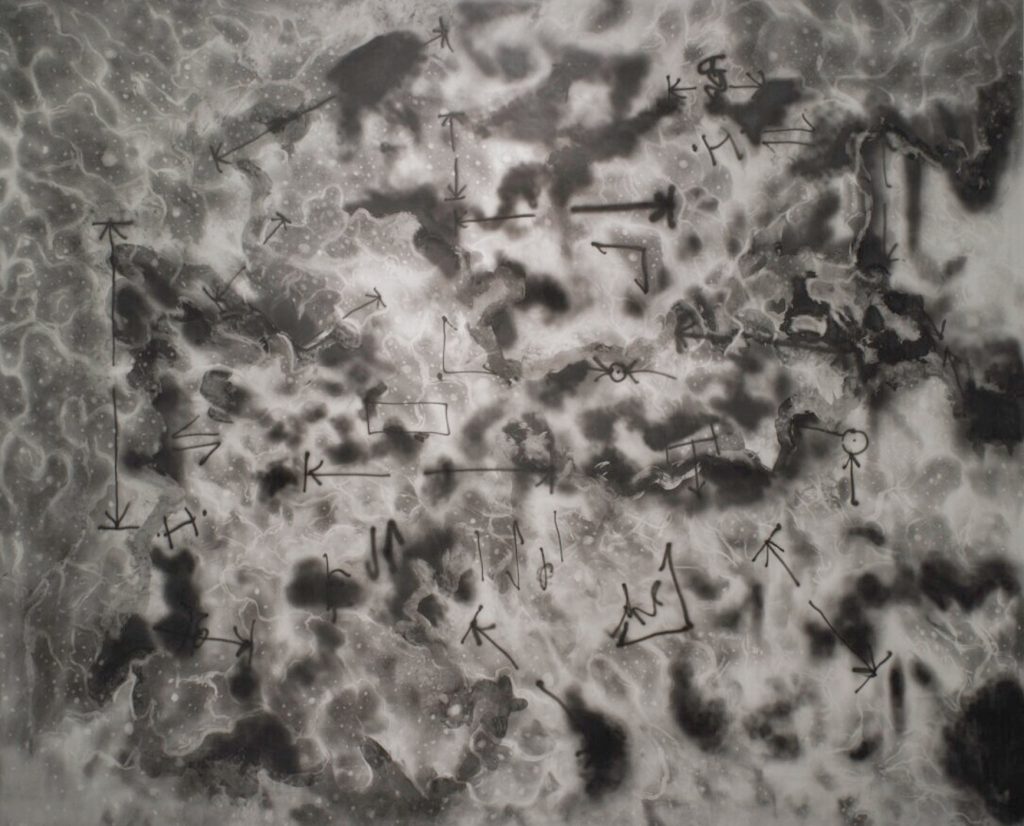

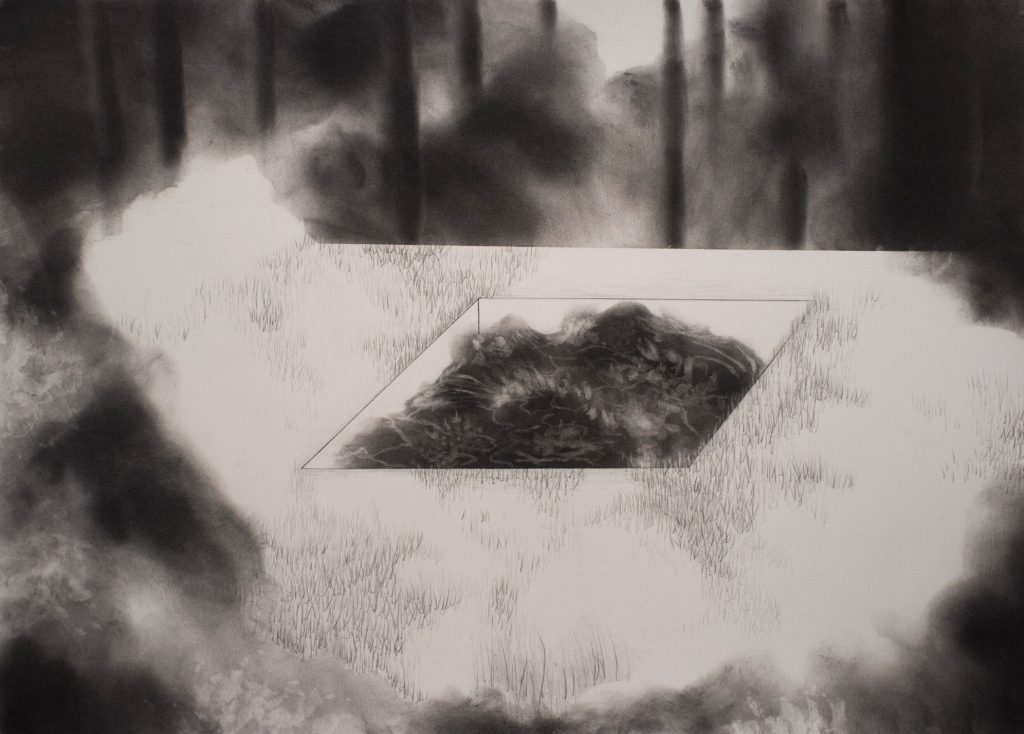

Andy Van Dinh: Good question. I find this hard to explain and Stuart Hall says it better than I ever could. It’s hard to explain because it’s hard for myself to fully understand or grasp. It’s like trying to talk about the unknown. And maybe that’s what I’m searching for – a way to discover a way to talk about what I exactly feel as someone in limbo – this really indescribable feeling. This imaginary rediscovery is a way to actually be able to go back and forth between the world where I am now and that of my roots, and to attempt to measure that distance between. I’ve used the imaginary as a way to look back at the emotions involved with assimilating and the fight against assimilation. Through drawing I feel like I can create ambiguous places or things that give invisible social forces some kind of tangibility. Or perhaps these are places that are an escape from these invisible forces.

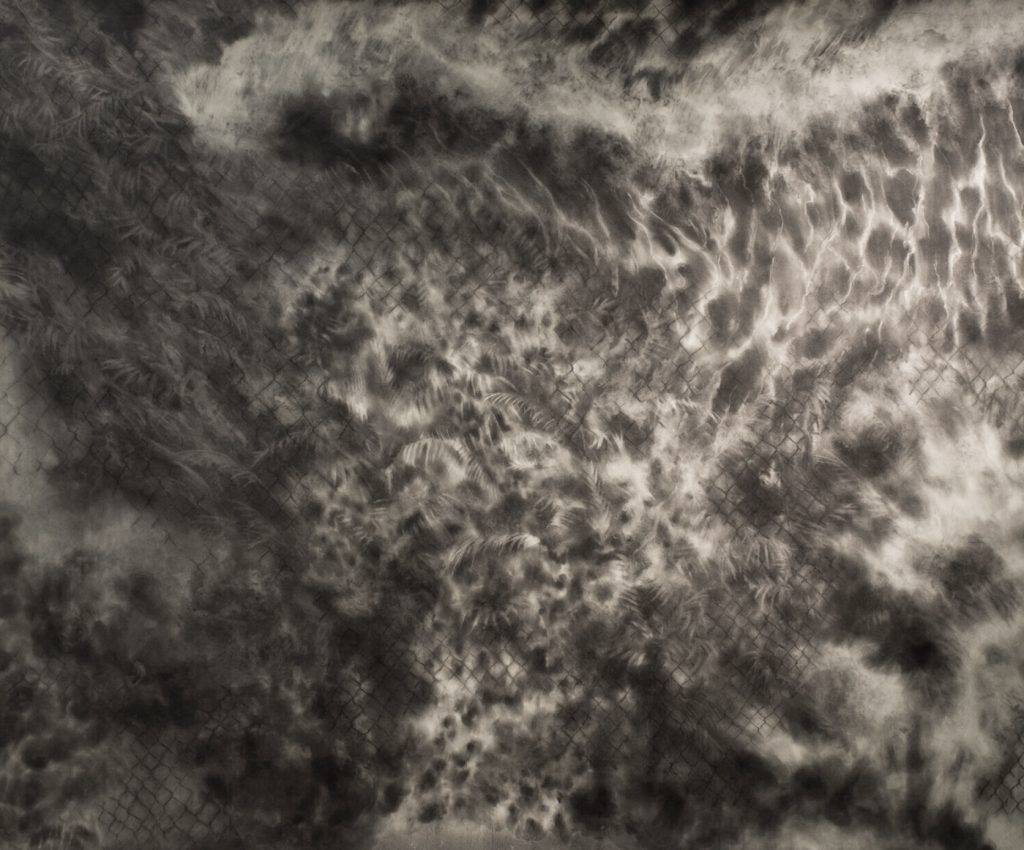

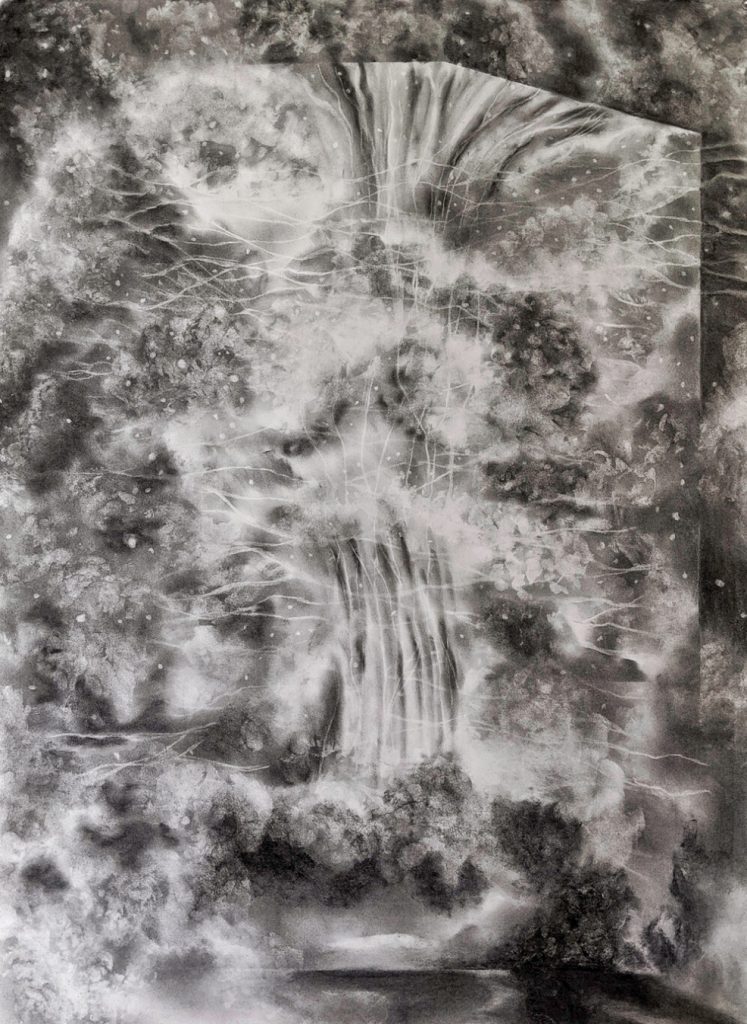

B O D Y: Images of water, palm trees, gaseous vapors and basketball court lines figure prominently in your work, where a kind of exotic and urban aura pervades. What’s your relationship to these symbols?

Andy Van Dinh: It’s funny because I didn’t grow up near a body of water or palm trees. These feel very foreign from my experience. They also have the ability to be many things at once. I think that’s why I started using this imagery. Palm trees can describe paradise, L.A, but it can also describe places such as Vietnam. Water and gas have this amazing ability to construe perspectives. Water can suspend you but also constrict you. Vapors like fog can make you feel something is near and far at the same time. Nature is beautiful and terrifying.Growing up I used basketball as a way to fight assimilation. I saw it as a counterculture to hockey. I started using it in my work at first merely because I just love basketball. But then it started to become a way to locate and measure. In Basketball, and many other sports, you’re attempting to get to the other side, while battling some kind of opponent who is trying to stop you from getting to that side. The basketball court started to reference body movement, boundaries, and rules in my work. There’s a lot going on and I’m still trying to unpack it all.

B O D Y: You traveled to Vietnam recently on a Travel Grant…

Andy Van Dinh: It was my first time ever visiting. My parents never really wanted to take me back because I think it was too painful for them. I felt like I was experiencing being the “Other” for a second time, but oddly enough at times it felt like home, like eating foods similar to what my mom would make me felt very comforting and familiar. Overall, going back to Vietnam wasn’t a final quest of return to the motherland where all my problems would be restfully concluded. If anything, it was a realization that we view Vietnam in such a small time period. American history has frozen time for the history of others. There is a ‘before’ and ‘after’ the Vietnam War. There exists thousands of years of history before the Vietnam War that makes me who I am.

B O D Y: That’s a huge shift in perspective… I rarely see drawing shown at the scale you work in. What led you to expand your practice to include installation?

Andy Van Dinh: I feel like it happened accidentally. I would make a random mark on a sheet of paper and eventually I needed more sheets of paper to continue the piece and eventually they were too big to show on the walls of exhibition spaces. So I let them exist on the floor.

For the tracing carbon paper pieces I was just in an art store and I saw tracing carbon paper. My mom was a seamstress and reupholsters furniture, so I grew up with carbon paper placed in piles on or around her work desk. It felt so strangely nostalgic for me and I thought maybe there’s something there. And then presenting the works became an issue because of the fragile materiality and the translucent marks I was making needed light to shine through the carbon paper. Different forms of installation seemed to be the right fit. The drawings were becoming something else when they were simply placed on the floor or inched off the wall. They started to transition and translate, displace and obstruct, which was paralleling my experience of movement.

B O D Y: The clothing patterns on the tracing paper – are they specific?

Andy Van Dinh: All the patterns are from my mom’s collections. She made clothes for my sister and I growing up as well as some clients she had. I think it was important for me to have my mom’s trace in the works. I’m still trying to figure out how I can use the tracing paper to speak about both my mom’s and my own experience with living and growing up in Canada, two generations, and the differences and similarities between us.

B O D Y: Yeah, that’s interesting. How did you come to working with graphite and charcoal?

Andy Van Dinh: I thought I was going to paint during and after undergrad. But then color became an issue. I just didn’t know what to do with color or why. Color all of a sudden became a scary thing. Drawing felt so direct, and so I thought if I could understand light first through drawing than color wouldn’t be as overwhelming. But then I found charcoal to be such a beautiful medium. It comes in different forms and it’s messy to the point where it effortlessly leaves evidence of where you’ve been in the studio and on the paper. In art history drawings are never seen as masterpieces in relation to paintings, and for some reason I connect to that underdog story. Maybe for me drawing can elude more towards the delicate, ephemeral, erasure, and negation, which are themes that have a place in my thoughts and works.

Further Reading:

To see more of Andy’s work visit his website: https://www.andyvandinh.com/