Daniel Barkley is a native Montrealer, born in 1962. He holds an MFA from Concordia University and his work has been shown throughout Canada and the United States in numerous group and solo exhibitions. Both the Musee des art contemprain des Laurentides in Quebec and the Justina M. Barnicke Gallery at the University of Toronto in Toronto, Ontario, have curated retrospectives of his work to date. Barkley was a finalist for the Kingston Prize and most recently, his figurative watercolors won the A.J. Casson Medal, awarded by the Canadian Society of Painters in Watercolor.

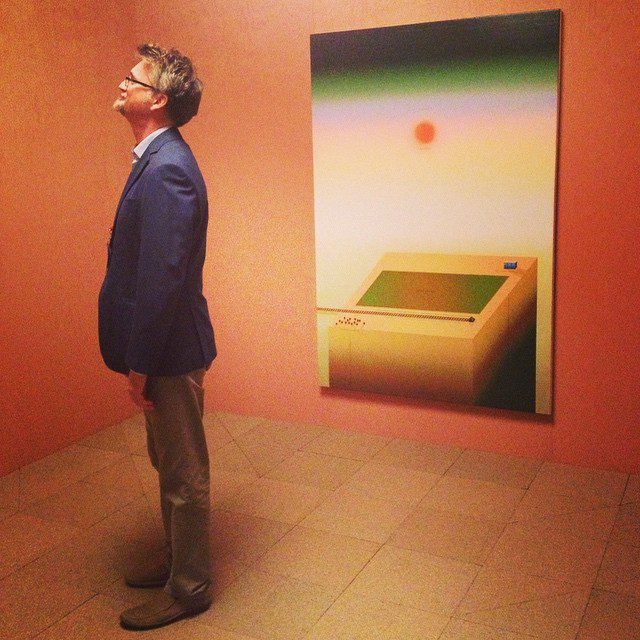

I recently caught up with Daniel Barkley following the opening of his solo exhibition at Galerie Dominique Bouffard in Montreal, Quebec. His work repositions the figure, as seen in Roman and Christian mythology, somewhere between current conceptions of figuration in painting and photography, and a more personal and oftentimes autobiographical context. – Jessica Mensch

B O D Y: There’s an interest in mythology among many contemporary artists. The work of videographer Mary Reid Kelley comes to mind among others. For you, a point of reference is often Christian mythology. Having lived in the States on and off now for a few years, I’m familiar with the anti-homosexual rhetoric espoused by particular Christian denominations. As a gay man, does this kind of discourse complicate your relationship to your subject matter?

Daniel Barkley: Not at all, the Christian Saints are a collection of weirdo’s – strange misfits who have visions, live intransigent lives, deny themselves and others and devote themselves to the silliest endeavors. The idea of the evil homo didn’t exist in the past; it’s a relatively new concept constructed by the Christian right. Homos have always been a part of society. Gay civil unions are well documented in Roman times and early Christianity.

B O D Y: You were just out of high school in the early eighties when a referendum was held over Quebec’s sovereignty. This question was preceded by two decades of major changes on all levels of Quebec society – from the secularization of education and social services to the creation and nationalization of existing mega projects like Hydro-Quebec. What was the cultural scene like for you at this time?

Daniel Barkley: Montreal was a very happening place then. Literally, I went to several Happenings – now called Performances. Happenings were always an eye-opening experience for this kid from the sheltered suburbs. The Neoists would regularly trash a gallery while one or two people took off their clothes. In Quebec this movement came on the heels of the Quiet Revolution where there was radical change in politics and art. This very cool moment in Montreal influenced me to leave painting and go into cinema, where all the cool kids were. Everyone was working on a low budget film or video project. It was very exciting and challenging and fun and groovy. At one point I was waiting to hear back about a grant to make a short film and decided to pass the time by painting. Compared to film, which is intrinsically locked to the duration of the piece, I really appreciated the permanence of the medium. When I returned full-time to painting, the AIDS crisis was here. Friends were ill or dying. My first paintings were really about this, but I was using old Christian myths as a framework to hang my experiences on.

B O D Y: What were those myths?

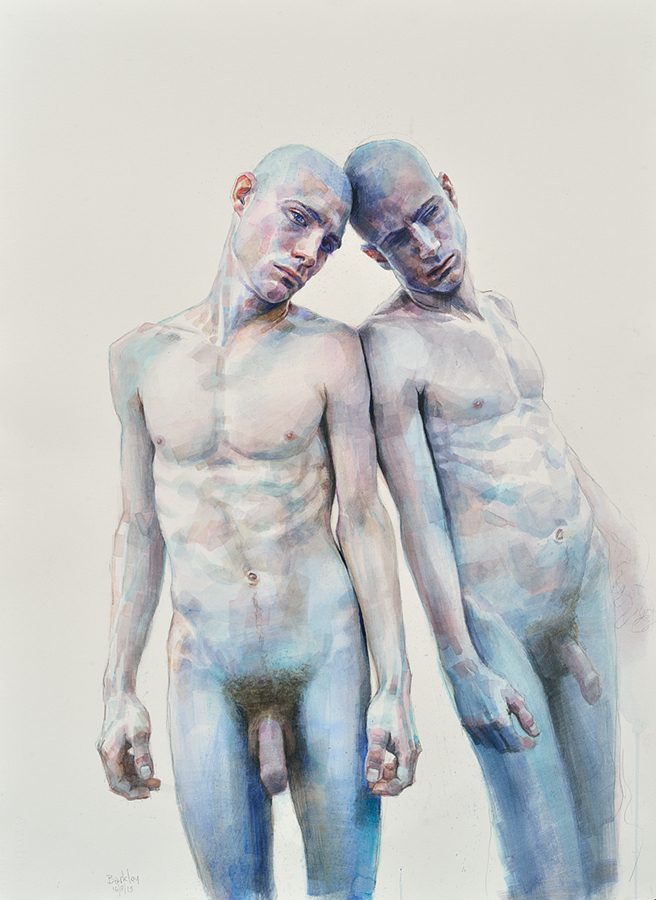

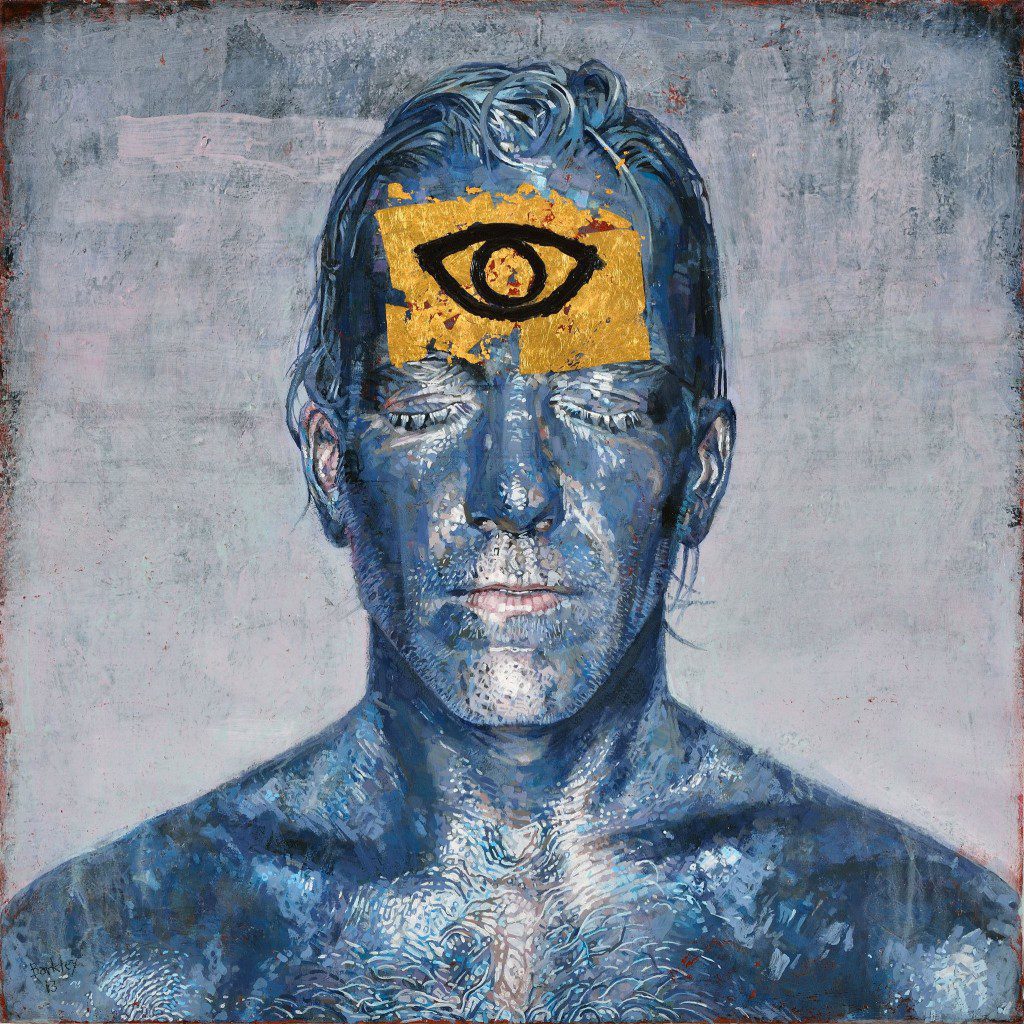

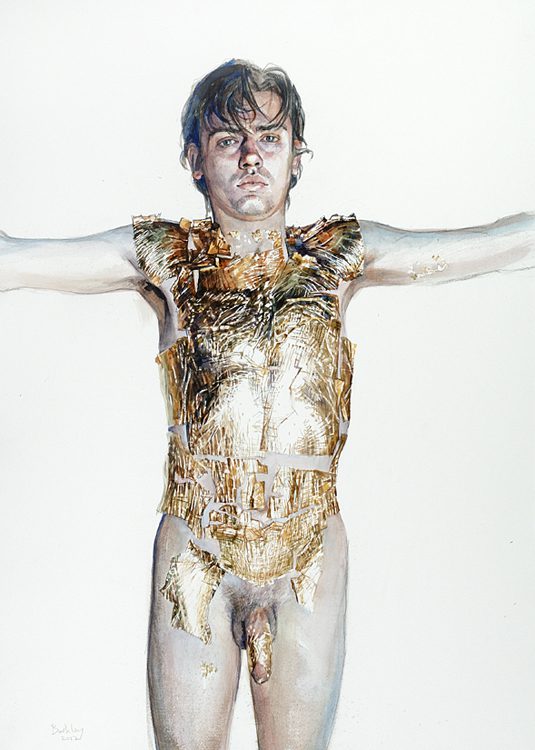

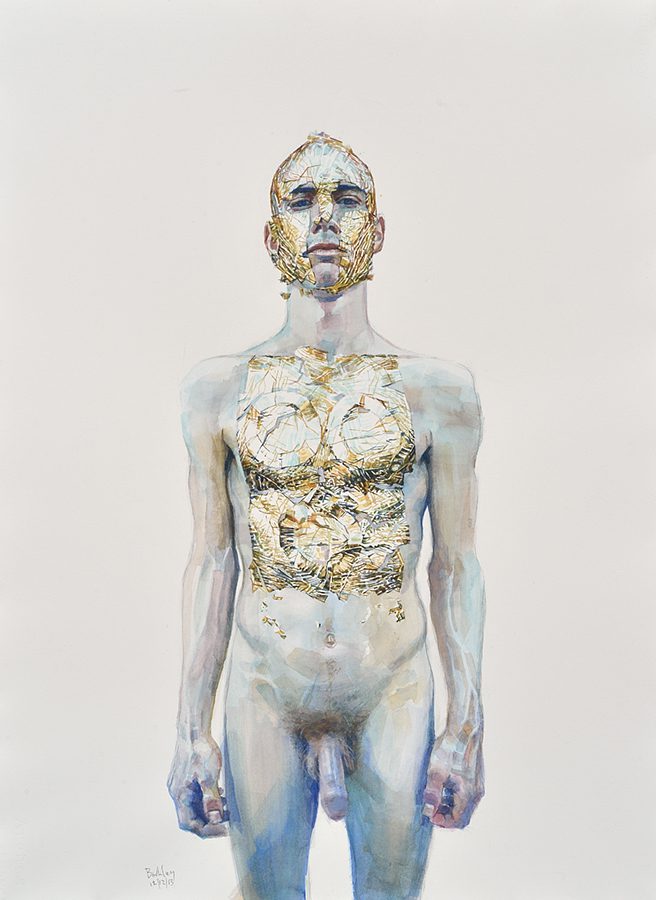

Daniel Barkley: Cheerful chestnuts like Saint Sebastian, Salome, Ship of Fools, The Harrowing of Hell and Judith Beheading Holofernes…For me Saint Sebastian was symbolic of the young gay man, diseased and dying from the poison arrows that pierced his skin. More recently I’ve rendered him with the arrows removed to signify his survival. During the time of the plague in the Middle Ages, this image of Saint Sebastian was often prayed to because Europeans symbolically associated the arrows with the Black Death.

B O D Y: The settings in your work stand in contrast to those found in Northern Renaissance paintings. They’re often painted with a muted palette and appear both sparse and expansive. Can you tell me about this.

Daniel Barkley: My landscapes are Canadian. I depict the landscape I grew up with – the shores of the St. Lawrence River. It can be very bleak there, especially in winter. This starkness has inspired my rendering of space. The shores of the St. Lawrence were a great place to grow up. When I was a child we could swim in the river but pollution has made that impossible now. These shores are my go-to setting. It’s where many of my dreams take place – many of my bad dreams. Pollution in it’s many forms, is a threat and major source of anxiety in these dreams.

B O D Y: The lighting in your paintings is very diffuse, which is unusual for figurative work because that kind of lighting tends to flatten the body…

Daniel Barkley: It’s a way of getting rid of artifice, of an imposed dramatic light, a theatrical light that is generated for effect and is perceived as false or forced. I try to pare down contrasting lighting to get to the essence of the drama.

B O D Y: That’s interesting. Flat lighting really does emphasize the linear qualities of an object or figure. Do you relate this graphic quality in your work to illustration?

Daniel Barkley: No. Illustration is always subordinate to a text. It interprets a text. My work has no text per se. There’s a title for a guide, but the viewer must decipher the piece by looking at it.

B O D Y: So for example when you’ve made a work that takes it’s narrative basis from a well known myth, where do you find the space to voice your ideas?

Daniel Barkley: Well for example, in The Rape of the Sabines, 2016, I did not want the ideas and emotions expressed in my painting to be driven by histrionics as it clearly is in older interpretations. And yet, I want to respect the tradition of having the Sabines inhabit a theatrically charged mise-en-scene. In this heightened, artificial reality the choreography acts as a formal element creating a circular motion from right to left, forcing the viewer’s eye continuously, endlessly, hopelessly around the canvas. I was hoping that the juxtaposition between the harshness of the choreography and the stilted, mannered “acting” would create a schism between what we are seeing and how we are meant to view it.

Lazarus, 2016, acrylic on wood, 24″ x 24″

B O D Y: I know you’re an active player in ARTSIDA – a yearly art auction that raises funds for Aids Community Care Montreal which is a community based organization that promotes awareness of HIV/AIDS and offers support and services for those in need. How did you get involved?

Daniel Barkley: I’ve been involved for 7 years. They approached me. They sent me a letter asking me to donate a piece for auction. I looked into the organization and saw that one of there many activities was to go into schools and talk to young people about HIV/AIDS. A lot of high school kids actually believe it is a curable disease, so I help them by doing what I do best – paint. I have friends who are living with HIV/AIDS, and it’s a way to honor them and my friends who have died of the virus. I’ve lived 25 years longer than many of them have.

Further Reading:

ARTSIDA’s website: ARTSIDA

Daniel Barkley’s current solo will be up at the Galerie Dominique Bouffard in Montreal, Quebec, until October 2, 2016.

And if you’d like to see more of work, here’s a link to his website www.danielbarkley.com