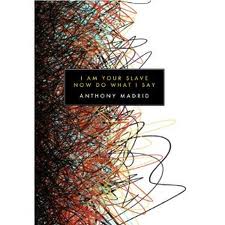

I Am Your Slave Now Do What I Say

I Am Your Slave Now Do What I Say

By Anthony Madrid

Canarium Books, 2012

Anthony Madrid’s debut collection of poetry, I Am Your Slave Now Do What I Say, is the poetic equivalent of a Bollywood dance routine: Rambunctiously over the top, colorful, humorous, and, even if by virtue of its own audacious strangeness, a thrill to witness.

One is tempted to say that the poems in this collection are founded primarily on a prolonged projection of a particular voice, that is, a kind of Middle Eastern Zarathustra in need of a Xanax, or a caffeine and opium-addled (read: more interesting) spin-off of Coleman Barks’ wonderful Rumi translations.

That voice, which essentially gives these poems their rich character, seems to develop over the course of the book, although its seeds are present even in the first poem, “Each And Every Time They Launch A Train Up The Tube,” which ends:

Whereas, MADRID is always at the ready with what he calls Golden

Advice.

He says we must write six books, every one of us. Let’s begin

with The Devil’s Dictionary.

The long lines, the pompous, third-person self reference, and an ear attuned to classical rhetoric, these are tropes that stay constant throughout the collection. The general tone is high-nosed pomposity, which extends even to the accent marks Madrid occasionally uses, to sneak another beat into certain words, a la Gerard Manley Hopkins. It is these elements of style that allow Madrid to turn even the most personal impressions into evocations of a kind of divine law, as in “No More Epigrams Against Sluts:”

No more epigrams against sluts. For it galls me to have to hear

These pig men and buccaneers complaining against every little

unauthorized blowjob.

Partially this is due to the voice Madrid employs here, which is over-the-top, to say the least, and joyously tongue-in-cheek. Much of the book, then, is like a hilarious ventriloquist act, if the dummy were delivering insights poignant enough to make you pause in language that is idiosyncratic and therefore intriguing enough to border on foreignness. The strange strength of Madrid’s voice also has to do with his references to ancient Eastern culture and characters like “Sa’di, that saintly sheik,” which Madrid juxtaposes with completely contemporary references, like “I came back to NYU and said ‘New York: always something to look at.'”

But Madrid’s poems are not built on voice alone. There are some stunning images throughout the collection, ranging from the surreal (and surreally accurate), like a description of the sun as, among other things, an “animator of bees.” In the poem “Whoever Worries Too Much About Being Believed,” Madrid posits this gem:

But the bruise on the fruit marks the spot where the biting teeth

will turn back.

Here, as throughout the collection, Madrid’s voice is insistent enough to seem nearly prophetic, which is an interesting choice when considered against the backdrop of much of contemporary American poetry, which is so embroiled in language itself and the meaning and possibility of meaning, that, as a reader, one often senses that poets are hesitant to present themselves too strongly, or make any definitive statement. Here, one gets the sense that Madrid knows exactly what he is doing.

And yet, there is a tongue-in-cheek self-deprecation throughout this collection, which creates a remarkable tension as Madrid balances audacious statements of opinion (“FUCK Buddha, I’m Buddha, nobody’s Buddha, quit talking about Buddha”), with insults against himself, as in “O You Beautiful Young Readers Of Poetry:”

O YOU beautiful young readers of poetry, and especially you

beautiful young men—

Have pity on my dried up talent. Forgive my reveling here in this

light…

MADRID, you effervescing piece of fuckass magma! anyone can

see

how much better this poetry would be if it were written by a

twenty-five-year-old punk.

It is hard to imagine that Madrid will continue utilizing this voice exclusively, as it would seem that such word-slinging would wear out the arm, so to speak. But what Madrid has accomplished here is real poetry, almost despite itself. No room here for candid meditations on life’s minute particulars; this is a collection of poems declaimed through a flesh megaphone atop a mountain where someone is manufacturing dirty bombs in a hermit’s cave. In this way, and without even remarking on the connotations of a mystic Middle Eastern voice from an American poet in the age of “terrorism” and revolutions throughout the Arab world, these are poems for our time. I Am Your Slave Now Do What I Say is truly contemporary, “un-fucked-with fountains” and all.

—Stephan Delbos

________________________________________________________________

Read Anthony Madrid‘s poem

A CELTIC KNOT WITH ITS LACES CINCHED in B O D Y.