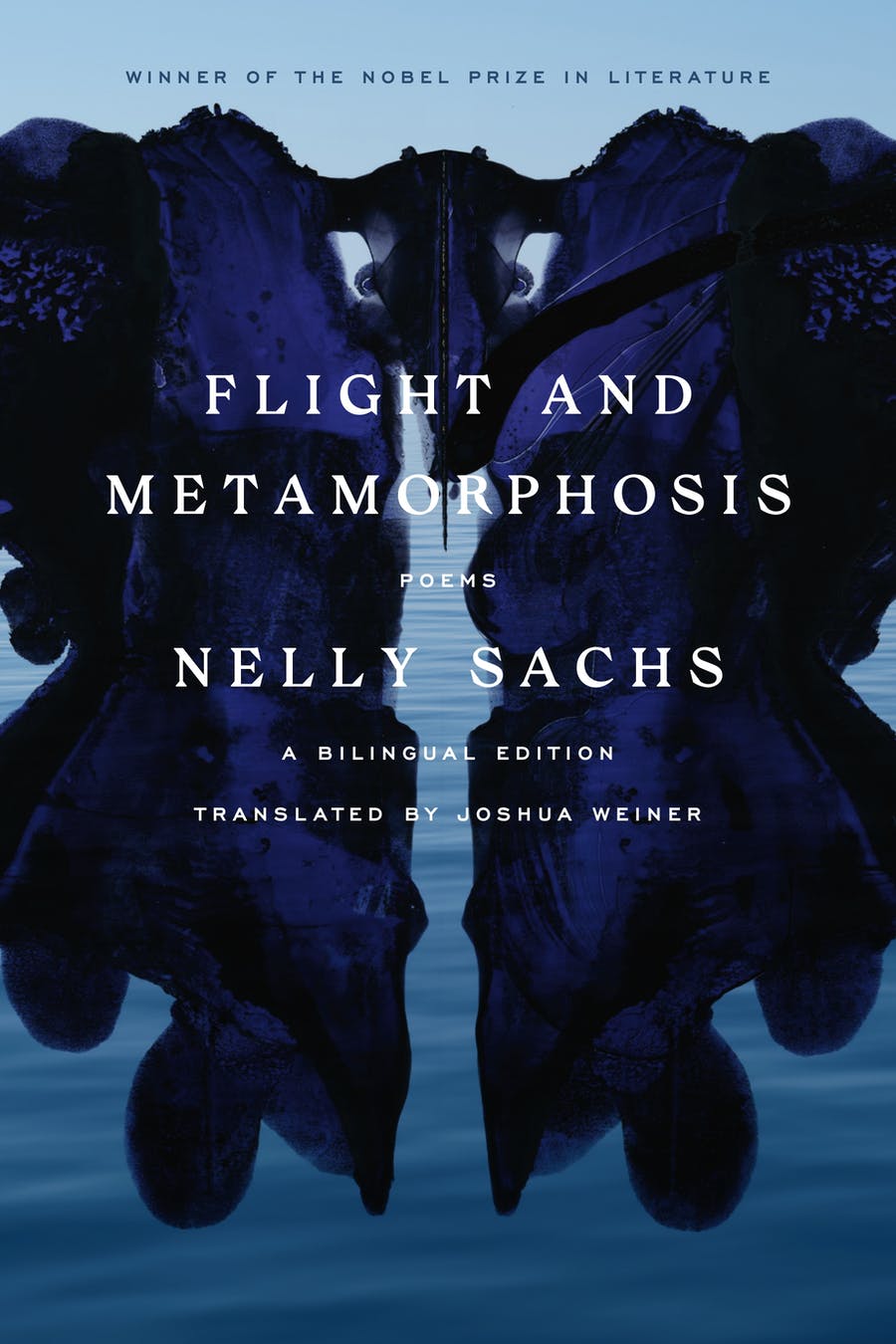

By Nelly Sachs

Translated by Joshua Weiner with Linda B. Parshall

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

2022, 208 pages

Nelly Sachs, the Nobel-prize-winning German poet, is one of the major figures of 20th-century Western culture. Several eminent translators, including Michael Hamburger, and Ruth and Matthew Mead, have translated her poetry.

In fact, most of the newest collection of Sachs in English, Flight and Metamorphosis from Joshua Weiner with Linda B. Parshall, based on Sachs’ Flucht und Verwandlung (1959), has already been translated and prominently published.

This may seem an inauspicious situation for an aspiring translator. Or an opportunity, if one feels the previous translations haven’t lived up to the original. In this case, the result is astounding. These translations hit home: they feel inevitable in English.

Comparing two translations reveals Weiner’s improvements. In “The Hunter” (or “Hunter” in the Mead translation), the Meads stay close to the word order of the German:

But how shall time be drawn

from the golden threads of the sun?

Wound

for the cocoon of the silken butterfly

night?

Weiner’s translation inverts some of the lines, creating a structure that seems more natural in English yet also closer to the spirit of the original:

Yet how should we pull time

from the sun’s golden threads?

Coil

night

for the silk butterfly’s cocoon?

Commenting on this poem, Weiner has said: “Night in this strophe sits apposite the sun; and I wanted to set that relationship by virtue of a more natural (to English) syntactic parallelism.”

Another difference is that the Meads have translated the German word “aufwickeln” as the passive verb “wound,” which can easily be read as the noun “wound,” as in bodily damage. Weiner circumvents this possible confusion and adds more agency to the lines with the active verb “coil.”

In addition to rethinking previous versions of Sachs, Weiner’s introduction frames Sachs’ poetry beyond the Shoah. He writes that the poems in Sachs’ collection In the Habitations of Death (1947), perhaps her most famous work, “remain, for me, very difficult to read–not because of their stylistic or formal strategies, but because she has yet to really travel in her work very far from her poetic origins in the German tradition, despite abandoning conventional meters, stanzas, and rhyming patterns.”

In Weiner’s English, Sachs’ poems utilize the strong, clipped language that we often see in Celan, but combine this with long, flowing, imaginative sentences that spin out through perceptions, no less carefully wrought for their fluid movement. For instance, the first stanza of “How Many”:

How many

drowned epochs,

in the rushing wake of childhood sleep

on the high seas,

enter the fragrant cabin,

play on the moon-white bones of the dead

when Virgo, with the nightspeckled

sun-lemon,

dazzles down

from the sinking ship.

The ocean recurs in this collection, as does the eclipse. These elemental images convey states of constant change that are beautiful and also vaguely threatening. Both oceans and eclipses suggest massive shifts of time and space that are far beyond human control.

As Weiner writes in his insightful introduction: “We are far, in Flight and Metamorphosis, from the ‘natural supernaturalism’ of Romantic poetry; rather we find ourselves in a poetic world where mystical artifice and natural objects join; where biblical prophecy and individual vision fuse; where concrete images transform with surrealistic fluidity; and where abstractions move in colorful animation.”

Sachs wrote these poems in Sweden, where she fled with her mother in 1940. After more than a decade in exile, translating contemporary Swedish poetry, studying The Zohar, a Jewish mystical text, and contemplating her former homeland from afar, Sachs deepened her awareness of the relationship between word and spirit and embarked on an evolutionary poetic journey in Flight and Metamorphosis. She would win the Nobel Prize seven years after the publication of these poems.

This book is divine. Sachs’ poems are exquisitely crafted in German and in Weiner’s English, but they are also divine because Sachs and her latest translators are aware of a higher power in language. For Sachs, to work with language was to stay in touch with the divine, and broadening the possibilities of language broadened the touch-points between humans and the divine, offering more ways to understand the power and all-encompassing breadth of the Creator.

Themes of flight and metamorphosis animate each page of the book. These poems explore the changes wrought by flight as in fleeing from, forced travel, emigration, leaving with no guarantee you will return, sometimes knowing you won’t. Sachs was familiar with painful changes of location and emotional scope, as well as the joyful, sometimes unexpected transformations that come with gradually discovering your own life in a new place, a new culture, landscape and language.

The poems in Flight and Metamorphosis also meditate on the changes effected by love and memory. These lines from the ruefully beautiful “Line Like” for example:

The evening

is throwing the springboard

of night over the crimson

lengthening your headland

and I place my foot, hesitating,

on the quivering string

of death, already begun

But such is love–

These lines, like so many others in the book, are alluring and haunting. And far from the devastating public lyricism of Sachs’ Shoah poems, there are poems in Flight and Metamorphosis that express a mellow rapture and a poise that can only be called wise. These poems ground an epochal point of view in the cultural and religious sensibility of scripture and Jewish tradition:

Hallelujah

at the birth of a rock–

Mellow voice of the sea

flowing arms

up and down

hold heaven and grave–

Sachs’ poems are wise. And they are stoic. And yes, sometimes cryptic, but often astounding. Weiner has rendered the powerful, haunting poems of Flucht und Verwandlung in accessibly magisterial English. Flight and Metamorphosis will stand as a crucial contribution: the definitive English translation of this collection, one of the most powerful Sachs wrote.

Nelly Sachs was much more than a passive poet of witness. She was a stoic, vatic poet wrestling with the limits of language and our ability to comprehend God in a world exiled from innocence.

–Stephan Delbos

More Nelly Sachs in B O D Y:

Five poems by Nelly Sachs, translated by Joshua Weiner

An interview with Joshua Weiner on his experience translating Nelly Sachs