The rich tradition of communing with the dead through poetry stretches back from the magic and metaphysics of Lucie Brock-Boido to James Merrill at the Ouija board, Jack Spicer and Jean Cocteau at the radio, W. B. Yeats at the seance table, and Odysseus in the underworld.

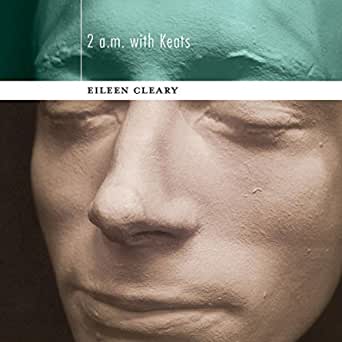

In her new collection, 2 a.m. with Keats, Eileen Cleary brilliantly contributes to this tradition with captivating poems that pay equal attention to the visible and the invisible worlds—and seem hauntingly comfortable in both.

The book, which is dedicated to Lucie Brock-Boido (1956—2018), begins with the poems “Elegy For Lucie,” “Moon Goddess Takes Leave of the Sky,” and “Lucie Asks About My Childhood.” This first section grounds the collection in Cleary’s close relationship with Brock-Boido toward the end of her life and creates the ethereal atmosphere that permeates the book, which dwells on the cusp of life and death, here and the hereafter.

“Elegy for Lucie,” a series of short, sharp lyrics, describes the first of the book’s incantatory visitations. The poet here is a careful listener, picking up and transcribing signals from the beyond:

Since your last visit, I’ve listened

for you. In a screen door chain,

chattering against its inner window.

Or the shift of dishes in their rack.

Much more than a poetry of poltergeists, this opening sequence crystalizes the book’s disquieting mood as Cleary switches between startlingly clear image and aphoristic wisdom:

A loud moon

shivers, No. I shiver.

Because I can’t convince myself it’s you.

This earth is a lonely fit.

These short lines are uncanny yet inviting, eloquent yet down to earth.

The book’s centerpiece is the twenty-page sequence “2 a.m. Keats Visitations.” Here Cleary conjures that beautifully lugubrious Romantic poet with short stanzas separated by empty parentheses. Like Dickinson’s dashes, these curious punctuation marks are both declarative and merely suggestive, calling our attention to what is not there by delineating the void, if only a tiny piece of it.

“2 a.m. Keats Visitations,” like the entire collection, is a threnody for the deaths of both Keats and Brock-Boido and touches upon—tenderly yet unflinchingly—the deaths that must be, inexorably, part of life for all of us. The poem exemplifies the delicate, deft handling of emotion that characterizes much of Cleary’s writing:

Your apparition sings

in the corner of my room —

then listens, your ear warm

and veined, trained toward me.

( )

How is it that you made

your way to me? Are you

interplanetary? Have you

cut through elderberry?

( )

Lucie said she —

I thought you might be her.

Which makes this the first night of peace.

The cattle at the fence, breach —

chew the same grasses

the bay mare gnashes

while I absorb what consumes you.

( )

I want to ruin the rumor

that the master’s dead.

( )

I know you’ve felt it too.

Death that separates you.

( )

My condolences on your silver dove.

Myself — when I’m grandmother

I’ll be neither wolf nor whale

but hoarfrost in still weather.

The silver dove at the end of this characteristically melodic passage is an allusion to Keats’ “Sonnet: As from the darkening gloom a silver dove.” That poem, which Keats wrote on the death of his grandmother, describes the soul’s ascent to heaven.

Other poems in the book that allude to Keats, including: “Fears that You’ve Ceased,” “Tuberculosis,” “Death Mask,” and “When I Return Your Visit John Keats,” show how deeply Keats—and Brock-Boido—are woven into Cleary’s language and thought.

One of the most startling images in the book comes from the opening of “Orphan Sky,” and alludes to the death of Keats’ father after falling off a horse when the boy was eight: “Don’t say the father died; say night falls / as if a father off a horse.”

A deep empathy warms this book, even as the poems sit comfortably with mortality and its attendant sorrows. Cleary seems too experienced to be even half in love with easeful death, and these poems display a quiet courage and hard-won sense of equanimity as they plumb the depths of loss.

Cleary, the co-founder and editor of the Lily Poetry Review and Lily Poetry Review Books, is also the author of Child Ward of the Commonwealth (Main Street Rag Press, 2019), another powerfully poignant collection that mixes memory, emotional attachment and letting go. 2 a.m. with Keats resonates deeply. These lyric meditations on death, loss and living touch and inspire.

—Stephan Delbos