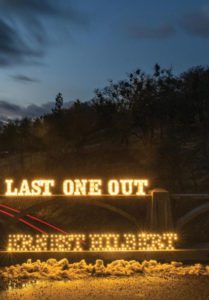

by Ernest Hilbert

Measure Press (2019)

102 pages

Ernest Hilbert is not an optimist. In his latest collection, Last One Out, the title poem addresses not only our individual mortality, but a kind of “last call,” a “hurry up please it’s time” for the world as we know it:

One day, the last host will slam the last door,

The last smoked ash will settle on the floor,

And he’ll look up, and stop, maybe toast

Himself, with the slow, confused motions of a ghost.

Nor is he a pessimist; the pessimist, expecting the worst, puts himself in the position of being sometimes pleasantly surprised. Rather, I think, Hilbert is a pejorist—things are going to get worse rather than better. It is a clear-eyed stance that nonetheless allows for some wonder at things as they are, some wry humor, some bonhomie. One day it will all be over, but even on that day, there will be hosting and toasting as well as ghosting. Last One Out is imbued with this feeling of belatedness, and serves both as a kind of middle of the journey reckoning and overview of career and ambition, but also a new starting out. The book’s epigraph is a tag out of Horace: Non Omnis Moriar—I shall not die altogether; something will remain. Is there possibly a glimmer of hope in this? With the title, Last One Out, perhaps it sets up an unresolved dissonance.

To give you an idea of Hilbert’s black-bile humor, his Eeyoric temper (or Yorick, perhaps), the title of his previous collection, Caligulan, is a word of his own coinage. Hilbert goes on for two pages giving a full dictionary entry for his newly minted adjective, a condition that denotes, among other things, “an abnormal and overwhelming sense of apprehension, marked by physiological signs … by doubts concerning the reality and the nature of an unspecified threat, and by self-doubt about one’s capacity to address it” or “an inclination to use threats and the menace of violence to keep a person or group of people in a state of intimidation and unease” and “a sense that something is very, very wrong.”

It’s eerie now, rereading these definitions, at how this speaks so specifically to the moment. Even eerier, though is the final sentence of the entry: First known use 2015, USA (emphasis, mine). The book, seemingly a product of the Zeitgeist, was in fact arguably prophecy of 2016 and beyond.

Hilbert’s debut, Sixty Sonnets (reader, in the interest of full disclosure: I blurbed that book, and have been a long-time reader and appreciator of Hilbert), made him something of a “bad boy” among the decorous New Formalists. The sonnets were saturated in alcohol, violence, literary allusion, and urban squalor; in them, muggers rub shoulders with fading academics. (Hilbert is neither, but perhaps on the outskirts of both highway robbery and scholarship: an antiquarian book dealer.)

The 2013 All of You on the Good Earth sealed his promise as master of the modern American sonnet, but pushed his range of subject matter: all the brows—high, middle, and low—Science Fiction, pop-culture, academia, the TLS, Philadelphia neighborhoods, World War II, the Cold War. “Zeppelin” in a Hilbert poem could easily refer to either Count Ferdinand Von or Led. The new collection is rife with “metal” references adumbrated in titles and epigraphs. In a nigh Venn diagram of Hilbertian subjects, a melancholy, let-us-sit-down-upon-the-ground-and-talk-about-the-sad-deaths-of-kings meditation set in a book-lined study cum Beowulfian Mead Hall is titled “As the Lost Kings Uphold My Side,” apparently a lyric from the “extreme metal” band, Celtic Frost. The potentially portentous title is thus leavened with irony: recollected in mature tranquility, the music of the poet’s youth maps the Dark Ages onto middle age.

The 2015 Caligulan built on the poet’s formal and technical range (longer poems in blank verse, shorter-lined poems in song meters), as well as the subject matter of an adult with grown-up responsibilities and concerns. The ancient world—it is worth remembering that Hilbert’s father was a music teacher, and his wife is an Etruscologist who works at the Penn Museum—starts to show through more, as in the 16-liner “Dominion of the Parthians,” an ubi sunt lament cum memento mori cum love song, that ends:

Galleries glamorous with gold and jade

Once gathered by war, too much to possess,

All seem to slip from me, become less true,

Now less to me than sitting here with you

And seeing that what little we’ve done

And all we have will just as well be gone.

This gentler, yet also larger and more melancholy, vision, is a preview of the poet’s turn in his latest work, Last One Out. Here a certain amount of youthful edge and swagger has been worn away, but is replaced by mastery, depth, and mellowed sweetness; the words I’m reaching for, I realize, might just as well describe single malts: aged and peaty, smoky and complex.

“Masculine” in poetry might mean a rising rhyme suitable to Anglo Saxon monosyllables. The adjective recently most likely to modify it might be “toxic.” But Last One Out is an exploration of another species of masculinity—one of tenderness and gravitas, regret and responsibility, anchored by marriage and mortgage. Dedicated to Hilbert’s father, the book begins with a memory of his grandfather (“German/ With shoulders of granite, / Of beer and blue skies/ blast furnaces”) throwing him as a small child into a river to teach him to swim, and ends on a sort of agnostic prayer for Hilbert’s own young son, Ian.

As the opening poem suggests, swimming or drowning, rivers and lakes will form one of the motifs of the book, but it is the second poem, “Yggdrasil,” (the title refers to the Norse World Tree that connects the nine worlds) that seems the key. Beginning in a kind of flexible terza rima (and continuing in tercets, although the rhymes start to align in different patterns), the poem describes a hurricane that uproots a beloved apple tree. But with the weightiness of the title, and an ending on “parched ancestral blood,” it is clear that the tree is both entirely itself, and perhaps a “family tree.” This might seem too freighted for a 34-line poem, but Hilbert achieves it by grounding the poem in closely observed reality, charged language, and slant rhymes that make the joinery visible:

A Bach cantata slurs to static

On the stereo as a hurricane

Rumbles through our attic.

Barrages of quicksilver rain

Machine-gun aluminum.

Darkness drags around the lawn.

While “drags” here is Plathian, the poem is perhaps most in conversation with Frost, that great poet of trees. In particular, I think of Frost’s “Window Tree,” where the tree of the window stands in some relation to Frost’s brain, one with its outer, one with its inner, weather. Here, too, certain words are suggestive of internal structures: “dendritic,” “capillary.” Later, we will learn that Hilbert’s father made arrangements of Bach for the organ, so the Bach cantata perhaps suggests the father; is the slurring perhaps a stroke? The apple tree does not die immediately, but “by parts,” and leaves behind (when it is removed), a “socket of mud” that “someday” “we” will fill. Why an apple tree? Because I would imagine there was really an apple tree. But if it wasn’t an apple, Hilbert would have chosen one anyway: not only the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, but because this ancestral family tree, with its roots in the earth and branches in the heavens, is also, surely, the tree from which the apple does not fall far.

Bach, and Dante, will return in a series of poems about Hilbert’s father, who died in 1992 when the poet was only 21. Recessional, in a terza rima that largely shrugs off rhyme, describes his father arranging Bach at the organ, while Hilbert, as a child, wriggles under the pews. The title, of course, is both musical and mournful, and the parent/child proportions (huge/rumbling/towering/looming versus small/under/inched/slipping) put charm and pathos into counterpoint. Hilbert, however, does not “weep like a child for the past.” The “safe gloom” is inviting, “deep and promising,” like, say, a snowy wood.

Hilbert is enjoying, mid-career, a new formal freedom, and with it, wider territory to cover, or perhaps vice versa. Sonnets still pop up (Hilbert even has an eponymous sonnet form, the Hilbertian sonnet), but there are couplets, quintets, sestets, 12-liners, and nonce forms. Hilbert rhymes when he chooses, but rarely seems hemmed in by a pattern or perfection, often opting for consonantal rhymes that hearken back to Heaney. The effect of his in-formed but un-rigid rubato and syncopation is musical. When he does perfect rhyme, it is often to pack a punch, as this poem (quoted in full) that might be a devastating volta come unmoored from the dreamy set-up of its sonnet:

Time and Tide

The mountain’s foot is soot in cloud shadows,

But light drops cool stairways over the sea.

Sails rise like teeth on the horizon, slow

Angles slanting and righting. I want to be

Alone here. I want you to suffer. I do.

I want those ships to burn. So do you.

That sharp twist, a flash of bitterness, is an anomaly in this collection, however. Only occasionally does Hilbert revert to this mode. Instead, we have some masterful ekphrastic poems (and not only of visual art, by Goya, Rodin, Turner, Velasquez, but music—Shostakovich composing his 7th symphony in Leningrad as “Strings shriek and strafe” and “Tympani detonate”), poems that meditate on intoxicants (Hilbert’s “Martini” summons the ghost of Hecht, but not, thankfully, the ghost in Hecht’s martini), poems on post-Cold War juxtapositions, poems of sailing and rowing. (It took me a stanza to realize that “Rowing in the Dawn,” abutting the poem “Kingsessing Avenue,” described not some scene in North America, but Oxford’s Isis.)

Hilbert is good at wryly skewering the rarefied worlds of academia and antiquarian booksellers. “At the 100th Anniversary of the Antiquarian Booksellers Association at the Royal Geographical Society” ends with the delicious:

The smiling chancellor, with a glinting gold

Shard of champagne aloft in his hand,

Calls for silence, and affable shushes spread

Like the last steam from an ancient engine.

Much of Hilbert’s new territory is occasioned by fatherhood—becoming a father himself also deepens the resonance of the loss of his own father—and here we see a burst of new forms and perspectives.

As almost any 21st-century parent will tell you, the anxiety about our children’s future, “a sense that something is very, very wrong”—a future that seems almost certain to be diminished from the futures we pictured for ourselves, in which, in their own lifetimes, they will see climate upheaval and corresponding societal tumult—can be overwhelming. How is poetry even to confront it: so many of the poems about planetary anxieties utterly fail as art even as they succeed as virtuous signals? (And yet, of course, poetry will outlast so much that is vanishing—for better or worse, there will be poems when there are no polar bears or monarch butterflies.)

Hilbert’s choice of Non omnis moriar, though, for the collection’s epigraph, suggests, if not hope exactly, perseverance in the face of diminishing returns. Wonder, beauty, tenderness are still being born, as in the love poem “For Lynn, at Lackwanna,” or Hilbert’s one-armed cradling of his infant son like a football on “Super Bowl Sunday.” One of my favorite poems in this collection, “American Glass,” describes a father-son visit to a glass museum—a list of shapes fantastic and familiar:

The summer ambers, peach, and arctic blues,

Crystal compotes that cradled cinnamon,

Citrus, cloves, and syrup, cut-glass jars

With cedar fragrances of Caribbean cigars,

Flint glass veined with daring spirals of cyclamen . . .

Ending:

Ale glasses etched with wiry vines and leaves

White butter dishes shaped as dreadnoughts,

Enchanted vessels made only to hold

The gruel, the wine and wind, the warmth and cold.

The poem is a cabinet of curiosities, a father/son idyll, a meditation on American history and empire, and a musing on mortality, on our fragile lives that are, nevertheless, “made” and “enchanted.”

The book closes on “Lesser Feasts,” as the poet renders a post-Christmas turkey carcass for soup, his hand “jellied” with rich fat, and observes, with some surprise perhaps, “Happy, we sort a small steading for our son.” It is a happiness that, in trepidation of the not-too-far future, roots itself, as it must, in the intermediate now:

Year’s end, and light’s begun to dispossess

The exhausted dark. I trace his small wrist.

May life, like light, be strong before it’s done.

–AES

A. E. STALLINGS is a U.S. poet, translator, and critic who has lived in Greece since 1999. Her most recent poetry collection, Like (FSG) was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. Her recent verse translations include Hesiod’s Works and Days for Penguin Classics, and an illustrated The Battle of the Frogs and the Mice (Paul Dry Books). She has received fellowships from the Guggenheim and MacArthur foundations. She can be found on Twitter @ae_stallings.

Read more by A. E. Stallings:

Poems and Translations at Poetry Foundation

Like: Poems, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux

The Battle Between the Frogs and the Mice, published by Paul Dry Books

Hesiod’s Works and Days, published by Penguin