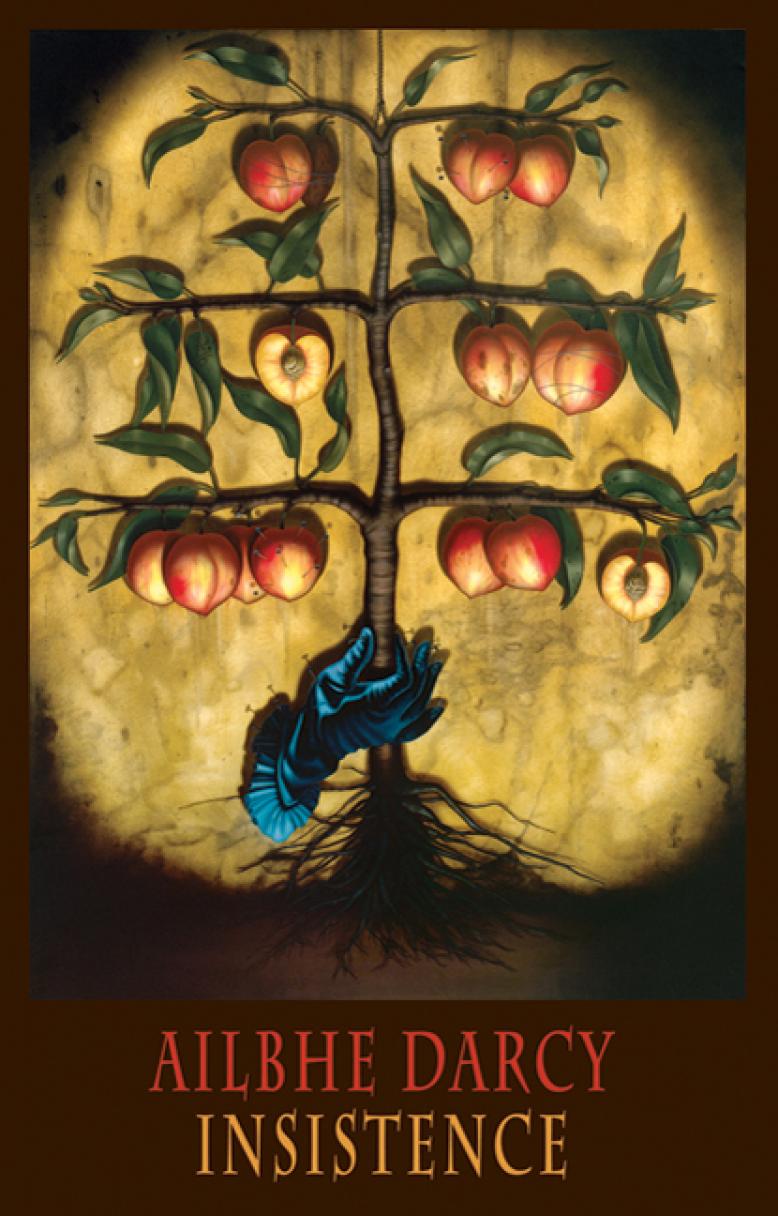

Insistence

By Ailbhe Darcy

Bloodaxe Books, 2018

80 pages

“But I’m not sure we’ll ever say the world is ours again, not sure we’ll ever really feel at home here again.”

Let’s start with this, one of the book’s epigraphs. When a quotation from John Jeremiah Sullivan’s “Violence of the Lambs” signals the entrance to a poetry collection I can sense that we’re not really supposed to feel steady on our feet. Not feeling at home in the world is all right by me. After all, feeling at home anywhere is not what we expect from poetry these days and certainly not from Irish poetry. For the job of contemporary Irish poet, one of the requirements must be to live elsewhere and at all times advertise dislocation. In this regard, Dublin-born Ailbhe Darcy is perfectly-placed having moved abroad (to the U.S.) to attend university, travelled the world (postcards are her forté) and set up residence (I didn’t say home) outside Ireland (South Bend, Indiana). As the Irish poet-critic David Wheatley has observed: in a typical Darcy poem, “identity is on the move with no clear sense of where it may come to rest.” Wheatley could just as well be describing his own poetry.

The poet’s only true home is in poetry and the most cosmopolitan Irish poets were early on asking what was meant by “home” (and rhyming it with “bomb”). Even before he moved to the U.S., Paul Muldoon (a major influence on Darcy) put “gasoline” in a poem, and in Darcy we find the same felicitous wordplay, particularly where the clashing of cultural and linguistic registers is concerned. Clearly a deep reader of modern and contemporary poetry, Darcy knows it’s all been done before. After all, as “Jellyfish,” a poem that forensically examines issues to do with the responsibility of knowing, ends with a deathly sting:

Once you saw a photograph

of a child –

lifeless –

on a beach –

so did everybody

We’ve seen it all. As a knowing poet who is no less a knowing critic Darcy seems determined to stay one foot ahead of her critics. “Perhaps we are all magpies,” Elizabeth Bishop (another presence in Darcy’s work) once surmised, and Darcy self-consciously takes her place among that thieving chorus. In “Caw Poem,” from her 2011 debut Imaginary Menagerie, “a solitary magpie / beats cricked wings / against my ribcage walls …. playing I-Spy with the gleams of a mind.” For Darcy, it’s all there for the taking.

Having been taken aback by the exuberance of intellect and imagination in Imaginary Menagerie I was eager to see where she’d go next. As one might expect from Darcy’s biography there’s lots of America in Insistence and the writing gains its intense force from the birth of the poet’s “American child.” In “After my son was born” we get the violent facts of new motherhood. For Irish poetry, this is breaking news:

Blood blubbed on my nipple

where his gums met. On the radio

somebody was saying something about Syria.

Coming up against that word “blubbed” reminded me of Simon Armitage’s “Poem” but Darcy makes it darkly startling in this context. Mention of Syria might seem gratuitous – reminiscent of Seamus Heaney’s criticism of how Plath’s “Daddy” “[rampaged] permissively in the history of other people’s sorrows” – were it not for what comes at the end:

He made everything heavy.

Like they say the bomb did for a while,

so that Americans swam

through their homes, eyes peeled,

picking up everyday things and dropping them

[…]

As though blood hadn’t always been there, waiting.

Plath knew this too, and Darcy knows precisely what she’s doing. She also hopes you’re paying attention: that heavy bomb is a nod to Inger Christensen’s alphabet (1981) which Darcy reworks in the long poem that closes the collection.

Lines of poems by others are at the tips of Darcy’s fingers throughout Insistence pinned down into her own sinuous, insinuating lines. The “Biltrite pram” in “Ansel Adams’ Aspens” is wheeled right out of Muldoon’s “At the Sign of the Black Horse, September 1999,” a poem which also features the poet as “bewildered immigrant” trying to make sense of his place in the watery world while his infant son (after Yeats’s “Prayer for my Daughter”) “sleeps on.” It is in the extended piece “Alphabet” that Darcy, inhabiting the spirit of another poet in translation, breaks into her own pattern of flight. As she has written of Christensen’s alphabet in a piece for The Critical Flame:

The poem notices itself singing and singing despite the bomb; it hears itself drowning out the sound of silence. Its form carries it to a crescendo of rapture. We come away from it humming, thinking not of what’s lost but of all that exists.

Icarus figures in Section 9 of Darcy’s “Alphabet,” and throughout this incendiary collection we see a poet stretching her wings, tentatively testing words against the contemporary moment.

What Darcy ultimately achieves is the art of insistence, of hauling the reader into a sidelong world in which they hardly know themselves, and words, kinetically-charged, insist on their own rousing reality. Here’s the scene in utero:

swinging his tiny jambs,

swimming the jammy mulch,

already sporting the tiny fore-jacket,

already yakking his jaw, the oldest bone,

already insisting, already jonesing,

already jimmying the lock 10, “Alphabet”

This is far from the by-now-obligatory ultrasound in verse. In many ways, resistance seems just as important a word as insistence throughout: we feel the tug and pull within the poetic imagination to eschew the typical response. Listen to that “jamb” and “jammy,” to the heated proliferation of present participles, the unrelenting anaphora (“already”), the invigorating slang – yakking, jonesing, jimmying – the imagination shining through metaphor. This is a fine example of Darcy channelling Christensen’s linguistic brio.

Darcy’s formal élan can be stunning. Along with her sensitivity to how space can be arranged around words she understands the art of repetition and how this movement in time functions as a form of life-affirming insistence. As Gertrude Stein explored in her 1935 essay “Portraits and Repetition”:

Is there repetition or is there insistence? I am inclined to believe there is no such thing as repetition. […] A bird’s singing is perhaps the nearest thing to repetition but if you listen they too vary their insistence.

Influenced, I imagine, by Bishop’s “The Armadillo,” the first section of “Postcards from Europe” is electrifying in its insistence as, in Belgium on St. Martin’s Day, the children’s paper lanterns (“not flares but sparks”) light up the viewfinder and the phrase “Europe dreams of burning, dreams of bombs” is reprised to chillingly hypnotic effect.

Obsessed with the poet’s role in a world under threat, attention is paid even to the unlikeliest of heroic subjects. In “Stink,” across fluid, three-line stanzas, we follow the stink bug’s journey into America: “First you tried Pennsylvania, then south to Florida / and north to Maine.” Hardly a compelling topic, perhaps, yet the strange sensuality of it teases us along; its Goblin-Market-like profusion of fruits and flowers making for a heady trip across borders and line-breaks. Of course it’s not just about the stink bug, any more than John Donne’s is about a flea; the theme here, pertinent for a poet who finds herself an immigrant, is that of invasion and the persistence of life in a hostile climate. Linkages abound: the closing image of the apricot tree has found its way from Christensen’s alphabet to Darcy’s own “Alphabet” (“apricot trees insist”). Elsewhere, poems give way to cockroaches, knotweed, silverfish, and mushrooms, the ubiquitous fungi of modern poetry – from Plath’s silent invaders to those of Derek Mahon’s disused shed – as the American rust belt becomes another place where a thought might grow.

“If you want me again look for me under your bootsoles,” Walt Whitman, poet of America, announces towards the end of his “Song Of Myself” (1855). Whitman’s “language experiment” never really ends and the same feeling of inevitable inconclusiveness overcomes one nearing the end of Insistence, which closes with the forward-looking line: “so this is where I look” as it insists exultingly on continuance despite the bracken “eking its way like a canker.” In many ways, quoting excerpts from these poems mutes their incantatory power: they have to be heard in full. Much like Icarus “in that split second / before the fall still as a hatchet fish” (“Alphabet,” 9) the whole collection writes itself out of a sense of language itself being on the brink. In the face of terrible knowledge, Darcy has managed the almost impossible here: a collection that, though written in time, seems to go on for all time. In Darcy’s fierce, word-shifting hands the future of poetry seems certain, even if nothing else is.

— Maria Johnston

____________________________________________________________________

MARIA JOHNSTON is a poetry critic based in Dublin. She has taught at Trinity College Dublin, Mater Dei Institute (DCU) and Oxford University, and her reviews and essays have appeared in a wide variety of publications; most recently an essay on Medbh McGuckian in the Cambridge Companion to Irish Poets (2018).