“We had lost confidence in our culture. Everything had to be demolished. We would begin again after the tabula rasa… We began by shocking common sense, public opinion, education, institutions, museums, good taste, in short, the whole prevailing order.”

So said Marcel Janco, one of the original Dadaists, explaining the beginnings of the anti-everything movement in Zurich in 1916.

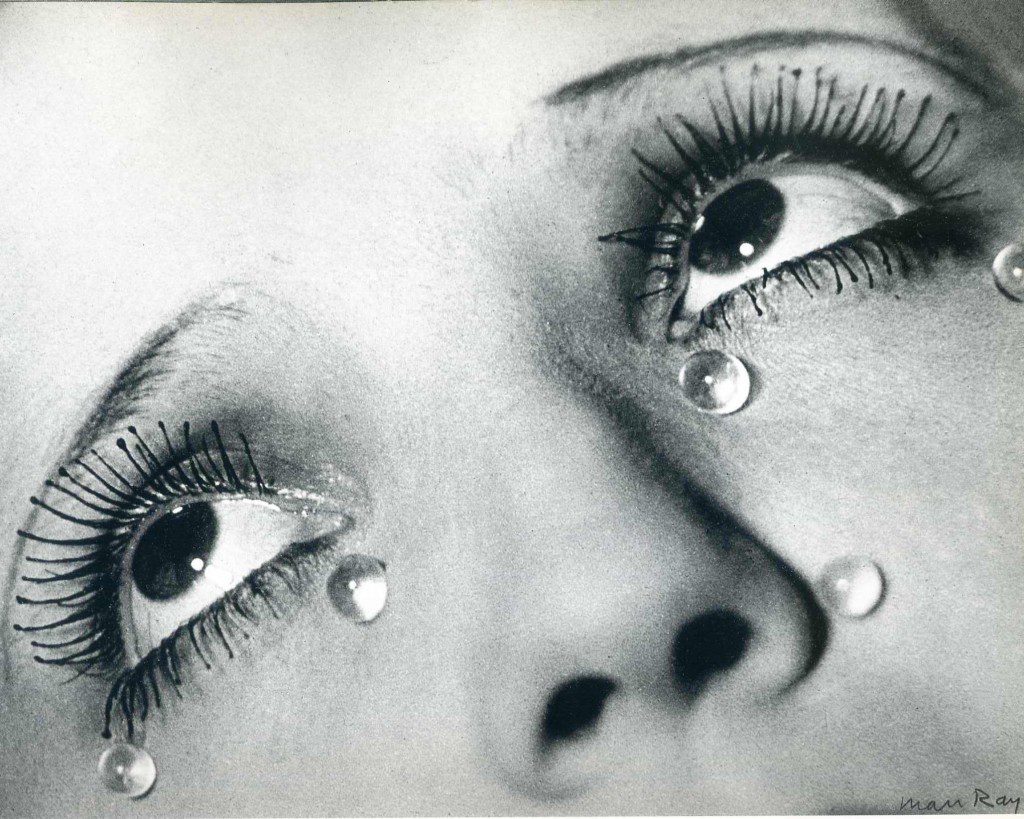

A year later, some of the most important Dada activity was taking place across the Atlantic, as French artists including Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia, fleeing World War I, settled in New York City and began to work with American artists including Man Ray and many others. Two of the intriguing results of this creative collaboration were ephemeral publications: The Blind Man and rongwrong. These short-lived little magazines made outsized impressions and continue to resonate today, especially with the publication of a handsome new boxset from Ugly Duckling Presse.

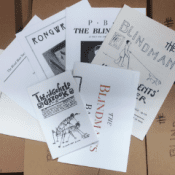

This set contains facsimile editions of both magazines, as well as a two-color offset reproduction of Beatrice Wood’s poster for “The Blind Man’s Ball” (1917) and a letterpress facsimile of Man Ray’s The Ridgefield Gazook (1915). Translations of French texts by Elizabeth Zuba accompany the facsimile reprints. Translator-Editor Sophie Seita’s detailed introductory essay provides invaluable context and insight to both of these publications and the larger cultural moment in which they developed.

Even the least-seasoned surrealist will know Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, the urinal he purchased from the manufacturer and installed in an art museum, forever altering the concept of the art object and, along with his later “ready-mades,” or works that were found and assembled from existing objects, cleared the way for conceptual art (and in the 21st century, conceptual writing as well). Love it, hate it, or feel indifferent, Duchamp’s Fountain is an incontrovertible and unavoidable moment in art history. What you may not know is that The Blind Man was the first publication to feature a photograph of Fountain.

The Blind Man and rongwrong were part of a larger moment of little magazines that brought some of the pioneering theories and works of the European avant-garde to an American audience. Featuring writing and art from the likes of Mina Loy, Erik Satie, Alfred Stieglitz (who photographed Fountain), and many others, these magazines were electric prods to the aesthetically inclined, and time capsules that capture the intellectual and creative fervor of a vital moment. The determinably, geniusly tongue-in-cheek gestures on every page of these publications were squarely aimed at the artistic and literary status quo. That animating spirit remains inspiring.

There is a wonderful spirit of play that comes alive here. But within this lightheartedness there is biting and trenchant commentary on the state of art in the United States, such as this excerpt on the importance and views of the Indeps (The Independents):

There are fine collections in New York, there are people who understand modern and ancient painting as well as anywhere else in the world. They are few.

For the average New Yorker art is only a thing of the past.

The Indeps insist that art is a thing of today.

[…]

American artists are not inferior to those of other countries.

So, why are they not recognized here?

Is New York afraid? Does New York not dare to take responsibilities in Art? Where Art is concerned is New York satisfied to be like a provincial town?

What chances have American artists who cannot afford to go abroad?

None.

These passages are prescient, coming just four years after the shattering Armory Show, which introduced American audiences (including poets like William Carlos Williams, Wallace Stevens and Kenneth Rexroth) to the European avant-garde for the first time, and two decades before World War II, when New York finally overtook Paris as the center of the art world. They show how these little magazines, while perhaps humbly printed, were poised on the cusp of great moments in art, and deeply engaged in the most pressing aesthetic questions of the age.

Besides the more famous figures such as Duchamp, these magazines are filled from cover to cover with interesting and important works from great, if currently obscurer, figures in 20th century art and literature. A poem by painter Charles Demuth – whose best-known painting, The Figure Five in Gold, was inspired by William Carlos Williams’s poem – is one of the unexpected highlights of this publication. Titled “For Richard Mutt,” it addresses the pseudonym with which Duchamp signed Fountain:

One must say every thing,—

then no one will know.

To know nothing is to say

a great deal.

So many say that they say

nothing,—but these never really send.

For some there is no stopping.

Most stop or get a style.

When they stop they make

a convention.

That is their end.

For the going every thing

has an idea.

The going run right along.

The going just keep going.

This unexpectedly delightful poem from a painter encapsulates the surprising wonder that charges these publications and this box set with a refreshing spirit of creativity that is carefree and sharply critical. These are innovative intellects poking fun at convention and making timeless art while they’re at it.

—Stephan Delbos