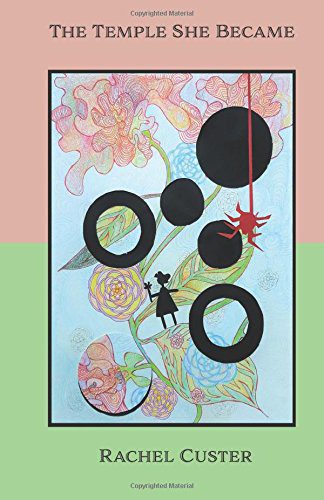

The Temple She Became

By Rachel Custer

Five Oaks Press

2017, 86 pp

I first became interested in Rachel Custer’s poetry last October when her poem “How I Am Like Donald Trump” appeared in Rattle’s Poets Respond series. I was drawn immediately to two things about this poem: its daring and its profound empathy. Few acts could have been more intrepid during the 2016 election cycle, especially in American poetry circles, than to empathize with Donald Trump. To have considered him human was audacious enough, but to have been willing to claim, in oneself, the same, tainted humanity, was nothing short of astonishing. Being a person who turns to poetry for empathy, for a chance to feel temporarily less alone in my brokenness, I was anxious to read Custer’s forthcoming first collection.

The Temple She Became, finally available, is a staggering debut. In lyric and ekphrastic poems, Custer explores what it means to be female in a world that feeds on feminine vulnerability, the wound witnessed violence opens in one’s life, and the horrifying longing for a God that may or may not be listening to our pleas. With its frequent themes of molestation and violence, The Temple She Became is not an easy book to read, but it is a beautiful book, a book that is deeply and disturbingly moving.

Rachel Custer is a master of foreshadowing. From the opening poem, “Christina’s World”—an ekphrastic inspired by the Andrew Wyeth painting—we are grounded in her native Indiana landscape but also upended by what occurs there, outside the frame, or, rather, inside the frame but beyond our vision. There’s a “yearling hung in the corn crib, gutted and a man with his blood-smudged cheek. And each girl [is] afraid to turn her back.” Custer imagines that this “picture of a house / hangs in the house in the picture / of a house on a hill // and so on,” so that the girl, should she try to walk away, will forever end up right back in the same place.

The past that is wrought here, deftly and in breathtaking detail, is devastating. Readers catch the first glimpse of it in “What the Spider Saw,” through the eight-eyed gaze of an orb-weaver who “saw, colonized, // the world called child – // the rippling abdominal forces of man.” Later, in “Schaulust,” the speaker herself “[splits] the small fingers supposed to cover [her] eyes and we watch alongside her, [her] sister—tiny, it seemed, as a lash— // pretend-napping naked in the hay. / You, like dark water closing above her eyes.” The vulnerability of these two girls haunts this book and will remain with readers long after they close its pages. There is “a girl curling herself into a dust mote and [her] pulse like a moth // caught flitting against the hollow of [her] neck,” and there is a girl watching who is willing to “swallow the blame fully.” Palpable and crushing, we feel the speaker’s guilt descend. It is the guilt of a survivor, of a witness, the aggrandized guilt of a child who is unable to look away from a catastrophe and helpless to impede it.

Custer presents the act of becoming a woman and the task of living a woman’s life as predicaments a person finds herself in. There is loss involved, and the situation is fraught with a quiet but steadfast peril. In “What We Didn’t Know,” a girl is “the skirt he ran / up the flagpole // cracking in the constancy of his wind.” Custer closes the poem “Descent” by saying, “(don’t touch me don’t touch / me I’m // blooming,” and the final lines of “The Tangled Garden” read, “[i]f there was / a girl, she’s gone now.” Maturation is, then, both an opening of the reluctant body to the world and, finally, a snuffing out. In “On the Other Side,” women stand together, being watched by men, “like empty beer cans atop a broken fence, / waiting for a little boy. The whip-crack, / the through-and-through // BB ping.”

Biblical language sings throughout The Temple She Became, but God, as he appears in these poems, is as much an absence as a presence. He seems to hover, helpless or inert or unwilling, and, like the speaker who was unable to save her sister, makes no discernible move to intervene in worldly suffering. This God “is in the monotony.” He is “like a cold hand in yours,” yet, still, the speaker yearns for him. In “Having Placed It Somewhere For Safekeeping, I’m Sure,” she tries to “find prayer in a hole in the dirt, in the emptiness of a / moment somewhere.” Her God remains the “[c]harred bones of a house / in which [she has] ached / to live.”

The book’s title, can, like God, be read in many ways. The she could be the speaker herself, or her sister, or could stand in for a more universal woman. To become a temple could be something good. A temple is holy. It is hallowed. Yet a temple is also a place built to house a God who refuses to reveal himself, where people take their suffering and beg for relief that, often, does not come.

Rachel Custer’s imposing command of language and preternatural control enable her to deftly navigate these enigmas, to lead her readers down very dark corridors with grace, to ravage us with a delicate precision. Though one feels lacerated after reading these poems, Custer’s implement is more scalpel than machete. “Again, and again, whispers the world,” to the speaker in “Out of Nowhere,” “you are nothing special, you are common as a household // carp.” But this debut—with its gorgeous use of language, its sucker-punch metaphors, and images so vivid they gave me aftershocks—is the work of a most uncommon talent.

— Francesca Bell

_______________________________________________________________________

FRANCESCA BELL’s poems and translations have appeared in many journals, including B O D Y, ELLE, Massachusetts Review, New Ohio Review, North American Review, Poetry Northwest, Prairie Schooner, and Rattle. She is the events coordinator of Marin Poetry Center and the former poetry editor of River Styx. Red Hen Press will publish her first collection, Bright Stain, in 2019.