THE GREAT EXPLORERS

This is what they knew: cold, solitude,

and the certainty of their ambitions,

which they would not have called

merely personal, although each wanted

to stand apart from the others.

Storms, sickness, delirium––

they could only afford

to imagine success, clear skies above

the final place. Then the arduous return––

losses of the dogs, of fingers and toes,

which did not surprise them.

Later they would begin their accounts

of the journey, each adding anything

that was needed, since the truth was now

whatever they made of their lives.

So it would be years before even

one of them wondered when

he might truly be forgotten,

or all but forgotten––transformed

into a note at the end

of somebody else’s book.

_______________________________________________________________________

REPLICAS

We were tooling along in Fred’s old jalopy,

thrown off our game

because the directions to the lunatic asylum were confusing.

I decided not to mention how appropriate

getting lost might be, maybe later

having to battle the elements to stay alive.

I’d been reading the old myths

and liked to imagine sailing through the clashing rocks

with only an oar for a weapon,

which wasn’t the most useful idea since we were heading

south of Tampa, trying to find our old friend

Adam, who might be waiting for a visit.

On the other hand, I thought, and then recalled

Adam having said far too often: On the other hand––

a knife is up close and personal.

People didn’t like to hear that kind of thing,

but we were sure he meant no harm,

even if in fact he did. We figured by now

he’d have forgotten the dangerous inclinations

of his youth, those days when he insisted

we’d all been misled by the voices

in our heads, then turned into replicas

of the people we thought we were. “Of course,”

Adam explained, “certain men choose

to be tempted by sirens. Others just let it happen.”

I told Fred that last part made sense, or sounded

like it should. “Damn,” Fred replied,

having taken another wrong turn.

“Not every kind of craziness makes sense.

Believe me, you’ve got to draw the line somewhere.”

At first Adam was upset about being sent away,

but since then we’d heard

he’d grown accustomed to the quiet gardens

they let him putter about in. We imagined

him kneeling down in the soil

like his name-sake and weeding

something small and green,

wondering why he’d ever believed

what he had, or else why no one

had ever understood what he believed.

Or perhaps both thoughts vanished

while he concentrated on his task, half-listening

to the murmuring of the more distracted guests

as they explained to each other how easily

they had been deceived by their lives.

_______________________________________________________________________

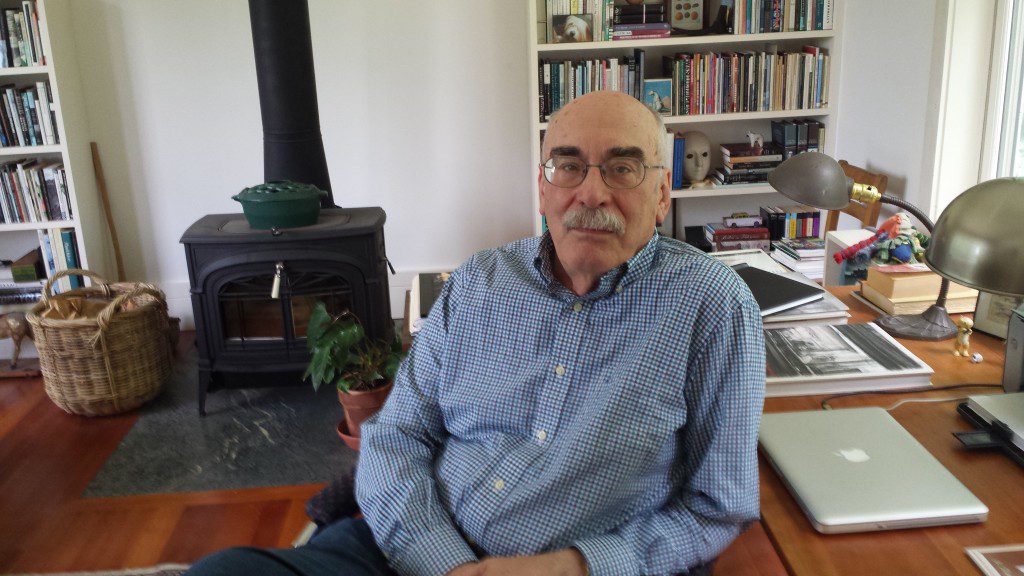

LAWRENCE RAAB is the author of eight collections of poems, including The History of Forgetting (Penguin, 2009), A Cup of Water Turns into a Rose (Adastra Press, 2012), and Mistaking Each Other for Ghosts (Tupelo, 2015), which was nominated for the National Book Award, and named as one of the ten best poetry books of 2015 by The New York Times. A collection of his essays, Why Don’t We Say What We Mean?, will be published in December of 2016. He teaches literature and writing at Williams College.

_______________________________________________________________________

Read more by Lawrence Raab:

Poems in the New Yorker

Poems at Poetry Foundation

Poem at Poets.org