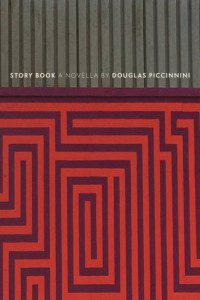

Story Book

By Douglas Piccinnini

The Cultural Society

122 pages

When confronted for the first time with the genre of “prose poetry,” any kindergarten student worth their salt will inquire why all fiction isn’t written with such attention to language. If, with a little more coaxing, prose can be made poetic, aren’t most writers just being lazy?

Douglas Piccinnini’s Story Book is not a book of prose poetry. But it does give an indication of what might happen when a novel is written from a poet’s point of view. The book is subtitled “A Novella,” but it’s easy to imagine other ways of characterizing Story Book.

This is a book of beginnings, a collection of stories that do not end. Each of the book’s 16 sections is a Chapter 1, and the stories themselves are linked mostly in their introspective narration, which hovers between descriptions of the surrounding physical world and evocations of the mental landscape of the narrator(s). There is a sense of personal insignificance here as the wide gap between intent and action is probed repeatedly. When the narrator of the book’s opening opening chapter says “I could begin if I could begin” he is not only echoing Samuel Beckett, whose Texts for Nothing is a dark touchstone for Story Book. He is also describing the mindset that pervades this book.

A book of story beginnings is not necessarily a book of false starts, and certainly not in this case. Instead, these chapters read like lines of flight, with various possibilities and directions outward stemming from a core subject which is the dreadful sense of helplessness and loss that hits us when we realize the unbridgeable gap between desire and outcome, between thought and speech, and between speech, interpretation and reaction from others. Like all of us, these narrators are watching themselves move through the world, bumbling, trying, trying again and trying not to blow it. A sense of astonishment, of a familiar world made stranger, is notable throughout the book, and due at all times to the sensitivity of the narrator and his desire to make these experiences and states of mind real by putting them into language.

There is a range of moods and uncanny situations in the book, from pure dread to humor, and they all feel lived. Take this internal monologue, which unfolds as the narrator is spitting out of his apartment window at people on the sidewalk:

My landlord at that apartment was an old Chinese woman named Sunny who was married to an old Jewish guy whose name I can’t remember, though I do remember one day I had my guitar out and I was playing and he came up and knocked on the door to ask me something. I couldn’t get up so good, so I just told him to come in. He let himself in and he saw my guitar and my leg propped up and I had my shirt off. He had a gravelly voice like Tony Bennett.

He said, “Hey, I can sing like Tony Bennett, why don’t you play and I’ll sing.”

But I don’t think that he really could, he just had a problem in his throat, but he sang acapella for a while anyway, while I just held the guitar silently in my hands.

Here reality, with all its strange detail, presses back against the language of the narrator, informing his thoughts. These moments of levity, and the richness of recalled detail throughout the book, make it compelling and concrete. In these moments, which are many, Story Book is more than prose poetry, more even than a novella, but is ultimately responsive and vibrant writing. That is perhaps where this book succeeds most: these are stories after all, and as any good yarn-spinner knows, you’ve got to keep people interested, through eclectic, electric detail and human interest. Piccinnini does that and more.

Douglas Piccinnini is best known as the author of poetry collections including Blood Oboe. The poet’s sensibility is clearly on display in these texts, which privilege language and tone over the usual architecture of plot and narrative arc. But where “a poet’s novel” is generally a backhanded compliment for a book that is descriptive to a fault, Story Book shows us how the poet’s conception of a text as self-sustaining can inform the genre of the novel or novella. Like different sections of a long poem, these chapters form a mosaic that suggests new ways of thinking about thinking about the world and writing.

The sections of Story Book feel less like fragments and more like memorials; to experience and to language’s power to suggest and sustain an individual’s sensibility, which is nothing more or less than the style with which a single mind moves through the places, people and events we call reality and allows reality to move through it, and in so doing move it.

–Stephan Delbos