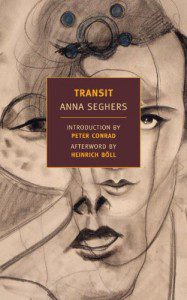

Transit, by Anna Seghers

Translated from German by Margot Bettauer Dembo

New York Review of Books (2013)

257 pages

At the end of November, Slate ran an essay by Joshua Keating on the 1942 film, Casablanca (‘Lessons for the New Age of Refugees’), reminding us that one of ‘the most famous movies ever made’ holds at its dramatic heart an ethical question that Europe and the US is currently asking: what is our obligation to help those fleeing political violence? The essay draws several fitting parallels between the refugees fleeing Germany in WWII (as are Victor Laszlo and Ilsa Lund, in the film) and the Syrians fleeing now from the triple crush of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, the Free Syrian Army that opposes it, and ISIS that opposes both and everyone else (the exhaustion and terror of flight; the terrible ennui and anxiety of waiting to register in another country; the effort of procuring false documents and other desperate acts of dissembling; of keeping one’s family fed, and safe; of avoiding or escaping sexual exploitation . . .). But the parallels are intensified by an historical inversion: the earlier migration of Western refugees fleeing war in Europe for the East has now shifted in the other direction, with other people. The film enthralls us, in part, with the growing feeling (Rick’s) of being morally gripped while not wanting to get involved, a tension that breaks with the resolve to step in and take risk: initial intrigue leads to plotting an escape; the plot spikes with physical action and the revelation of character and feeling. However much Rick’s heroism remains disabused of illusions, he overcomes his cynicism and wariness (read as a sublimated isolationism) by an essential overriding principle (also read as American) to help. A great movie, however creaky its structure and transparent its ideology.

As we look to the last century of popular myths to guide us like feel-good oracular dreams, I’d recommend we pay attention to literary works that do more to put us in meaningfully ambiguous relation to the difficult complexity of experience. The literature of exile — works born out of and reïnscribing the alienation of living as a stranger in a strange land — is legion, stretching back through the modern novel of immigration to the Book of Exodus. (Maybe Dante’s Purgatorio is the ultimate work of migratory aspiration, the progress of the soul up a steep and treacherous allegorical peak.) Is there also a literature of the refugee?

Anna Seghers novel, Transit (completed in 1942, published in 1951, and reprinted in 2013 by the New York Review of Books in a translation from the German by Margot Bettauer Dembo) is not unique in its apparent subject matter — the plight of refugees fleeing the violence of WWII — but strikingly strange in its treatment and self-reflexive obsession with acts of storytelling. Like Casablanca (which is its contemporary), Transit is an escape story, a run-from-the-Nazis story; but unlike Casablanca, the tension of stasis — of waiting, hiding, scheming — never breaks into any kinaesthetic release or ethical movement of conscience. Like most of life, it simply goes on and circles round, its patterns creating a feeling of unfolding meaning without drawing climactic conclusions that can be reduced into mottos of conduct and tattooed on the body politic. What lifts the novel from the mundane is not dramatic action, or snappy dialogue, or beautiful sentiments, but rather the constant correspondence with the stories, myths, and legends that form our collective consciousness and structures our perceptions. It’s a Casablanca without a plot, a thriller without thrills, a novel of pure intrigue and unsolved mystery — who we are, who we become when the forces of history uproot us.

Transit opens with our nameless narrator having already experienced the trauma of imprisonment and escape — not only from a German concentration camp (where he’s sent initially) but also from a French labor camp. How he got to Marseille — a historical point of departure for thousands of refugees who were lucky enough, in 1940, to make it that far — and what he’s doing there: that’s his story. What we find out as he begins the circuitous telling of the tale comes to us in pieces, narrative flotsam in a psychic sea of the unconscious. He doesn’t want to bore us, he keeps saying, but he can’t manage to tell the story in a straightforward manner. The trauma of camp existence, the witnessing, the fear, and the nerve required to escape; the running, the exhaustion, and the desperation followed by the tedium of refugee flight; the psychic stasis that follows once one reaches a point of rest; and the bureaucratic stymie he faces as he tries to move forward again by securing the elusive set of required visas, release papers, and stamps; the sequence of such experiences creates in the narrator a kind of mental sleepwalking through a maze of self-awareness: actions can be recounted, but understanding is impossible. Trauma has trapped him in a state of perpetual dream (Traum, in German). But the telling itself is not ‘dreamy;’ it’s rather matter-of-factual, as one might actually feel things in a dream. One experiences the textures of the real, even as time and space morph elastically, and the people one encounters appear suspended between states of mythic transformation. Formal narrative disruption mirrors the psychic break, the condition of political displacement, and the real plight of refugees caught in a constant emotional state of flight, even when they are no longer physically on the run. The feeling of desperation, that events happen outside of one’s control, or don’t happen despite one’s greatest desire; of needing to move even while one’s feet remain planted; of needing to stay even as one is swept along; of needing to pass through gates that remain locked and talk to people one can’t find but sense are just around the corner or in the café across the street; such states of tension, with no promise of release, capture the refugee condition, the feeling of being hopelessly entangled in a terrible dream without the possibility of waking.

Who is in control? Our narrator, an unnamed 27-year-old mechanic with no literary interests, has assumed the identity of another man, Seidler, having been given a set of the unknown Seidler’s discarded identification papers. A friend asks our narrator, now known as Seidler, to deliver a letter to a writer named Weidel, who is staying in a nearby hotel (the friend has already tried and failed to deliver it). ‘Seidler’ agrees, only to discover that Weidel has committed suicide in his hotel room. He offers to take Weidel’s suitcase off the hands of the hotel proprietor so she won’t get in trouble for having an unregistered guest. Later, in a fit of boredom, he opens the trunk to find an unfinished manuscript, which he sits down and reads from beginning to end, finding himself completely enthralled by the fictional narrative. No, even more than that, ‘I also felt,’ he says, ‘that this was my own language, my mother tongue, and it flowed into me like milk into a baby.’

It didn’t rasp and grate like the language that came from the throats of the Nazis [. . .] This was serious, calm, and still. I felt as if I were alone again with my own family [. . .] The whole thing was a fairly complicated story with some complicated characters. One of whom, I thought, resembled me [. . .] I had read entranced like this, no listened, only as a child. I felt the same joy, the same dread. The forest was just as impenetrable. But this was a forest for adults. The wolf was just as bad, but it was a wolf who bewitched grown-up children. And the old fairy-tale magic that turned boys into bears and girls into lilies took hold of me anew in this story, threatening again with grim transformations.

When Seidler, through a bureaucratic snafu, becomes erroneously identified as Weidel, he moves from feeling like a character in the author’s unfinished novel to feeling like Weidel himself. He reads the letter he was charged with delivering and discovers it’s from Weidel’s wife, Marie — she’s leaving him; but she needs him to meet her in Marseille: couples need to apply for visas together. She can no longer live with him, but she can’t leave France without him. This absurd paradox is no mere absurdity: unaccompanied women could end up interned. Although he knows he can’t take Weidel’s place as her husband, Seidler nonetheless steps into his second imposter role and travels to Marseille. But to do what?

The sense of a fiction unfolding without intentional design, improvised by psychic accident, as in a dream, grows stronger with Seidler’s persistent magical thinking. Even as he moves through the world as Weidel, he has an undiminished sense that somehow the real Weidel is controlling events and composing the very abject story of Seidler’s infernal stasis; it’s as if Weidel were himself a refugee, caught in the depths of the underworld and creating through literary composition Seidler’s reality. Or, maybe, Seidler thinks, he didn’t discover Weidel in a hotel room; maybe he was magically swallowed by a whale. (And in this novel, people do disappear, figuratively and literally, into the sea . . .) But the magical thinking in Marseille is not Seidler’s alone. Rather, it’s a kind of collective hallucination that gives transit papers magical properties as well as functionary ones: it transforms petty bureaucrats into hunchbacks and goblins while others take on the form of animals; events take on the force of biblical prophecy; and the refugees run into each other with a circular regularity that conveys the patterning of legend and myth (Seidler, who feels marked on his forehead with a secret sign, is also plagued by a persistent orphic fear of looking backwards).

Such a summary makes Seghers’ novel sound like a kind of magical realism, but it’s not. It’s a psychological realism that nonetheless teases out a continuous web of allusions and metaphors — nothing magical ever happens; no real transformations ever take place. Figurative actions and classical allusions, which in the narrative have an obvious literary status (but a pre-literary origin), are also characteristic acts of perception: we think and perceive in such terms of inherited narratives, emblems, topoi . . . Reality is not super-real; it is only super-saturated in our acts of perception with the cultural work called storytelling. The frame of reference that gives shape and meaning to reality, to experience, includes a form of thinking that is both magical and real in the mind.

The interplay between the levels of myth & legend and the plane of reality on which the real plight of refugees plays out remains constant and charged by Seidler’s urgency and fecklessness, his sense of shame, and the conflict he feels between wanting to stay and wanting to flee, wanting to connect with others and wanting to abandon them; all the while propping up a flimsy fantasy that he can, in the end, against all obstructions, romantically win Weidel’s wife, Marie, even as she secures passage on a steamer departing for Mexico, and with another man (a doctor, again on the run).

Anna Seghers, who was herself a refugee from Hitler’s Germany (she was arrested by the Gestapo in 1933 for being a Communist; she was also Jewish) launched from Marseille to Mexico in 1941, having successfully wrangled first a visa, then an exit visa, then a transit visa, and finally the necessary stamps for departure. She renders the refugee condition and state of mind with painfully exquisite precision and detail that many would recognize today, with 60 million displaced, even down to the controlling metaphor that we read and hear everywhere to describe the mass migration of those fleeing political violence: moving water.

The stream of the departure-obsessed swelled steadily hour by hour, day by day. No police raid, no decree by the Prefect of Bouches du Rhône, not even the threat of concentration camps, could keep the number of those hoping to leave from surpassing the number of people living here permanently. I considered all those who had already departed as refugees in transit. The refugees passing through this place had left behind their real lives, their lost countries. They were fleeing the barbed wire of Gurs and Vernet, Spanish battlefields, fascist prisons, and the scorched cities of the North. I knew many by their faces. No matter how alive they pretended to be, or how animated their talk about audacious escape plans, colorful outfits, visas for exotic lands, and transit visas, nothing fooled me about their plight. I was only amazed that the prefect and the other authorities and officials of the city continued to act as if the flood of departures could be dammed by mere human means. I was afraid that I might be caught up in the tide [ . . . ]

This inescapable plight takes on a timeless dimension. As we recognize how fittingly such descriptions, penned in 1941, capture aspects of refugee experience today, so does Seghers, through her conceits and allusions, indicate a recurring experience that maybe is even part of our evolutionary story. ‘Refugees it seems,’ says Seidler, ‘have to go on fleeing.’

This perpetual transit effects even those who, like Seidler, end up wishing to stay; for such permits, in Marseille, are only given to those who can prove that they intend to leave. This ‘catch-22’ avant la lettre is one of Seghers’ brilliant strokes, the bureaucratic double-bind inducing a kind of fever state of desperation in refugees who must wait a month or two months for the next ship to arrive (and as you wait, or try to get one visa, another visa obtained might expire; then your ship sails without you, and you must buy a ticket for passage on another ship that won’t arrive for another month, and so you must again petition to stay longer etc. etc., the mythical agonizing dream loop of panic and stasis always impressing with the weight of the real, or, as Seidler describes it, the ‘chunks of reality that enter into our dreams’).

In the meantime, the refugees stuck in Marseille have nothing to do but circulate among the cafés, eat pizza, drink bad rose and ersatz coffee, and tell each other the harrowing stories of loss, betrayal, and confusion, mixed with the intricate infective obsessive narratives of obtaining this or that piece of government paper from bureaucrats whose eyes penetrate deep into every applicant.

Heinrich Böll, in his afterward, calls Seghers’ artistic command a ‘somnambulistic sureness’ of style and narrative. More than any other novel written out of such distress of die Flüchtlinge (literally, in German, the fleers, the word for refugees), Seghers creates a spectacle of shadows indelible as any film. The novel does nothing to model a heroic pose that we can flatter ourselves with by imitating in the theater of our own self-assuring fantasies; it induces, instead, the experience of being stuck even as we flee, actively interpreting our own dreams. In the end, that may be a better spur to sympathy, which is the first principle of any good ethics — today, tomorrow, soon, and for the rest of our lives.

–Joshua Weiner

_______________________________________________________________________

Read more by Joshua Weiner in B O D Y:

Reviews:

Gift and Gear: The Work of Thomas McGrath

Uljana Wolf & Christian Hawkey’s Sonne from Ort

Poems:

Poem in the March 2015 Issue

Poem in the October 2012 Issue

Two poems in the September 2012 Issue

_______________________________________________________________________

Read Joshua Weiner’s Berlin Notebook in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

Entry 1: ICH BIN EIN BERLINER? (February 4th, 2016)

Entry 2: BEING A REFUGEE IS NOT A PROFESSION (February 5th, 2016)

Entry 3: REUNIFICATION DAY (February 6th, 2016)

Entry 4: WHERE WERE THE REFUGEES? (February 7th, 2016)

Entry 5: I WAS BORN IN A REFUGEE CAMP (February 8th, 2016)

Entry 6: THE GREATEST OF MOTIVATIONS (February 9th, 2016)

Entry 7: THE PROBLEM OF THE “PROBLEMATIK” (February 10th, 2016)

Entry 8: GERMANY IS MY DESIRE (February 11th, 2016)

Entry 9: STILL AS A TOMB (February 12th, 2016)

Entry 10: THE INSIDER OUTSIDE AND THE OUTSIDER INSIDE (February 13th, 2016)

Entry 11: STATELESSNESS (February 14th, 2016)

Entry 12: PEOPLE WILL MOVE (February 15th, 2016)

Entry 13: SHABBAT DINNER (February 17th, 2016)

Entry 14: BERLIN’S “QUIVERING HEART” (February 18th, 2016)

Entry 15: JOSEPH, THE YOUNGEST JEW OF IRAQ (February 19th, 2016)

Entry 16: CHARITY BENEFITS THE GIVER (February 20th, 2016)

Entry 17: MAKING SOMETHING OF IT (February 21st, 2016)

Entry 18: REFUGEES BRING NEW ENERGY TO GERMANY (February 22nd, 2016)

Entry 19: COMING HOME (February 23rd, 2016)

Read the entire Berlin Notebook here

Read Joshua Weiner’s essay on the Berliner Ensemble’s production of Bertolt Brecht’s Mother Courage and Her Children at Tikkun.