The Notebooks

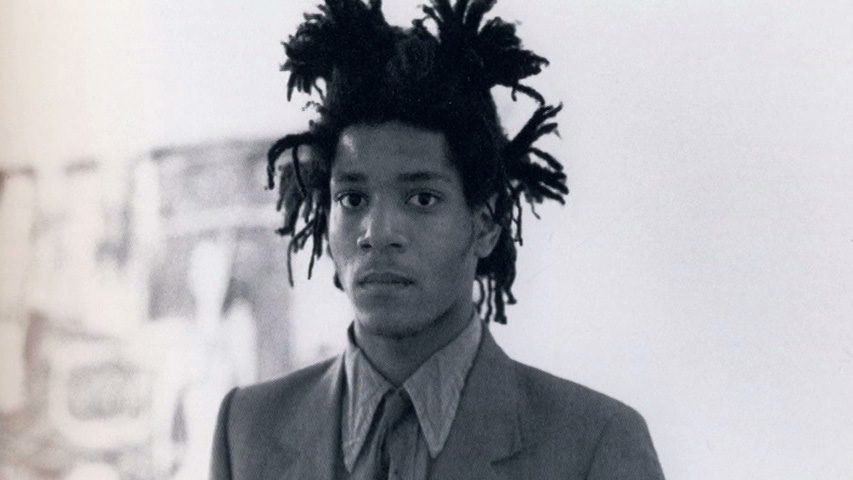

By Jean-Michel Basquiat

Edited By Larry Warsh

Princeton University Press, 2015

As an object, The Notebooks by Jean-Michel Basquiat is one of the most interesting books published in recent memory. A facsimile edition mimicking the classic Mead marble notebooks in which Basquiat scribbled, complete with dirty masking tape, coffee stains, phone numbers and dusty footprints, the volume collects eight of the New York artist’s personal notebooks from 1980 to 1987. That not every page holds the same energy and interest as the book itself is no fault of Basquiat’s, for these notebooks are just that — catchalls for anything that drifted through the artist’s mind, from random phrases to drawings, phone numbers to poems — idea breeding grounds that were never meant to be published.

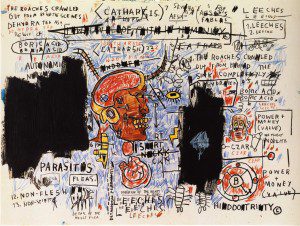

Yet readers of these notebooks receive a strange reward. Those who are artistically inclined will find the beginnings of some of Basquiat’s most famous drawings here, including “Famous Negro Athletes.” Those taking a literary approach to the book will find striking descriptions, strangely appealing turns of phrase, and drafts of poems that — interestingly enough — seem remarkably up to speed with contemporary avant-garde American verse.

At times, these pages are little more than notes to self, offering interest to the biographer, or anyone daring enough to call “MARYANN” at “228 3968” just to see if she picks up. (She didn’t). Another entry reads, in its entirety:

NEW ORLEANS–

BUS — 159.60–

FRENCH QUARTER

THE COLLUMNS — HOTEL

Other entries are more striking in their odd power, achieving a kind of poetry without scaffolding:

ANTS ON A CHICKEN BONE

WORKING MEN BREATHE THE DIRT OFF

THE BIG WHITE

WHITEBREAD WITH THE CENTER ATE OUT

A BALDHEADED BOY ON A BICICLE

TEXTILE WASTE

A BIG ALBINO BOY COMES IN THE DINER

2 COKES FOR A BIG BODY

There’s a roughshod literary appeal here, a kind of brut poetry, spelling mistakes and all, that is analogous to the urbane primitivism of Basquiat’s art. Because Basquiat regularly used poetry in his paintings, these pages often give the reader the feeling of inspecting the x-rays that would eventually flesh themselves out on canvas.

Some of the entries in the book capture the uncanny energy of the best of Basquiat’s artwork, while hinting at the diversity of influences from high and low culture that informed his style. One entry tells a story of bebop legend Charlie Parker in surreal, street-wise language:

IN STOCKHOLM THEY HAVE THEIR ROACHES IN A ZOO.

A COMBINATION OF WORRY AND THOUGHT–

A FOURTEEN YEAR OLD SWEDE IN NEW YORK

1959. — GOES TO BIRDLAND AND BEGS

TO BE PHOTOGRAPHED WITH CHARLIE FUCKING–

BIRD PARKER__SHE SHRUGS HIM OFF–

CHARLIE MAKES HIM BUY ALL HIS RECORDS–

SWEDISH CHOCALATE SOLDIERS

Few of the entries in the The Notebooks are distinctly autobiographical, but the one poem that seems to communicate clearly about Basquiat’s life is also one of the most affecting pages in the book. Entitled “PSALM,” it reads, in part:

THIS IS NOT IN PRAISE OF POISON

ING MYSELF WAITING FOR IDEAS

TO HAPPEN-MYSELF-THIS NOT

IN PRAISE OF POISON IS THIS IS NOT

NON

THE NOUN POISONOUS POISONED

SO SELF RIGHTOUS POISONED

NO ONE IS CLEAN

FROM RED MEAT TO WHITE

POISON

Every book is meant to be read differently. Some are studied, some are put up with, some are enjoyed, and some are admired. In this sense, The Notebooks is a book for all seasons — it is a text and an art object at once, adding a new dimension to our knowledge of Basquiat’s thought. It brings us under the surface or behind the scenes, whichever metaphor you prefer, showing the artist at his most protean, and pure, stained with the life that rarely slows down long enough to be captured in words.

–Stephan Delbos