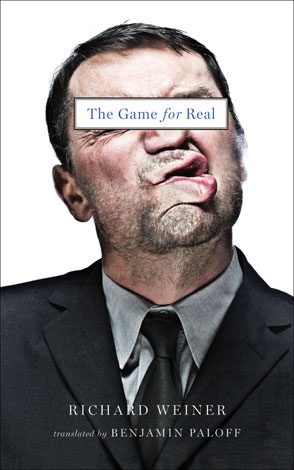

THE GAME FOR REAL

(an excerpt)

The Game For Real

A novel by Richard Weiner

Translated from the Czech by Benjamin Paloff

Published by Two Lines Press

He was lying on his back. He had an urge to touch his eyes. They were dry. Not that they might have gone dry again; no, he had learned, not knowing how, that they hadn’t gotten moist to begin with. And for this stubbornness on the part of his eyes he hated himself just a bit more. – He squinted and noticed a clump of bellflowers. They were luminously blue. At the same time, he also noticed everything that had transpired since yesterday; at first glance, it was compellingly material, but in this blueness that materiality as if melted away markedly. He immediately sensed that, really, “the weight had lifted off his shoulders.” How his creditors had hounded him! And all at once, after all the quarrels and threats, after all the badgering, and when he least expected it, they offer him a reprieve. – It’s paid off! All of it, with interest.

Lunch is served in the yard, at small tables. His is right next to the stream: he’s got it covered. He’s visible to everyone, and everyone to him. It’s a table, and more than that it’s a hideout, an impregnable hideout. He’d be happy to see someone dare rise, approach, and address him: “Sir, I’ve had enough of you, get up, scram.” – He would say, standing with dignity and leaning against the covered tabletop: “This table is rented, sir. I’ve paid for it, the payment was accepted, so I am here by right.” – Rent is more reliable than ownership, safer, more secure; property can be expropriated, declared-unpaid for, criminal, ill-got, but who has ever denied someone’s right to a rented seat at a theater? – The call to lunch will come in a moment; he’ll settle into his theater seat; he’ll have a good view; he’ll let them have it one after the other, one after the other. He’d be happy to see who would dare harass his paid-for, rented hideout! No one can deny him his right to the table! What a sense of power! Of safety! At his own table, there’s a taboo. Would the fellow over there defy his gaze? Should we find out? Let’s bet on it! – He sees it as though it’s already happened: he fixes his eyes upon him, him there. The table is like an electric switchboard, he paws at it: is the fellow over there resisting? Push a button: aha! The resistant eyelids are lowered. As though he’d cut them down in a line. Just let them dare to come to his hideout! Poor them! – They don’t suspect that it is he who is generating this dangerous current—now that he’s finally understood where Shylock drew such great strength from: He’d paid! He’d paid! – You there, do you know how to get the better of this current? And with what? With words, really: words? But which words? There’s the rub: there are innumerable words; the point is to find the one among them that inoculates against a legal rejoinder. Aha! I say against a legal rejoinder. But what is a legal rejoinder? We’ll explain, we’ll explain: Suppose that a hardened provocateur steps forward. One who would keep his eyelids fast. Who would meet the gaze behind the hideout with the lance of his own gaze. Bon! But now tell me what this provocative look could say other than “you’re the one who had been suspected of theft yesterday”? – And so what? – Suspected—haha!—suspected! And what about the proof? After all, will he waste his time mentioning that there had actually been proof? Aha! But it was proof of his innocence; ah, of his complete innocence! – Fine! So we’ve found someone who provokes. Fine! But how could he provoke, except by lying? So what do we do with him? Still, no explanations, no proof? We’ll skip it. – Here is the look that doesn’t want to be averted. Fine! So then what lying slanderer will withstand two certain syllables? These: “Riffraff!”?

“Riffraff ” is a lovely word. Its sound and appearance would merit better content than has been consigned to it. Gold is poorly distributed around the world. – “Riffraff.” – Such a winsome word, and what has it been condemned to! – “Riffraff.” – Such a sonorous word! Say it to yourself once, twice, and the scowled tinkling that hatches through the distinct layers of the midday shimmer immediately looks different. And what is that sound, anyway? It doesn’t have the cheerful quality of bell-ringing, it has the crabby stress of a call to labor. It’s the midday gong consigned to the housemaid Bela. She’s hammering it with an acrimonious thought toward the most disagreeable moment of the day: serving at table. – He gets up; he says to himself, “Riffraff! Riffraff!”; he’s delighted by what a corrective and winsome word it is; it’s a surprise he doesn’t say it to himself in a marching rhythm. – Now here’s the last bang on the gong; he’s slipped through the gate he’d hobbled to after the impossibly narrow and uneven footpath, along which he is also now embarking in the opposite direction. Here’s the yard, the tables are bare, they’re gleaming. He lifts his head, as if he were taking someone for his witness, but he already knows the testimony beforehand: it’s started to drizzle; it’s drizzling. – Lunch, under special circumstances, is served under the roof.

Here’s the glass door to the winter dining room. It’s as unyielding as an old miser; it can be coaxed just barely a bit, if you’ve tilted your head in a certain manner, then it grudgingly lowers its resistance: from it you’ll deduce that the interior is a kind of white point without it being possible to figure out its whole; and there’s the gliding of human shadows rather than the shadows themselves. They’d eaten in the winter dining room the day before yesterday as well. Farewell, hideout, farewell, stream that watches his back and lends him courage! He’ll be forced to sit between any two. I guess we take a bowl from somebody and give it to somebody? How do we look someone straight in the eye if we’re sitting next to them? And if he answers “riffraff!” with a kick to the shin, how do we ascertain who’d kicked whom under the table? And then: he doesn’t have his own place at the table, no magical isolation—the crowd and the crush.

This rain! Like a teammate playing outside the agreed-upon rules. If he were now to say “I’m not playing,” who would hold it against him? But let them: this round is admittedly different from what had been agreed, but he’ll push through it anyway. He’ll pass to them. He swears that he’ll pass to them, but he swears to them no longer as an avenger, but rather as a captive, on his word of honor. There are a few other people sitting at the table, and across from them—nothing. . .They’d already come to him yesterday, they’d sympathized with him for the awkward misunderstanding. If it just happens that he’s forced to dine with them at a shared table, he knows what behooves him: no provocations with looks; he has no right to disrupt the lunch of people who’ve done nothing to him . . . But what then? Eat with one’s nose to the plate? Receive bowls with an exaggerated “thank you” and pass them on with a humble “thank you”? – And it would be the sort of thing where he couldn’t stick a slightly decorous and “biting” irony into his “thank you” and “please”; where he couldn’t enjoy a nice sprawl in his armchair during dessert, lift his head and say while chewing, “Alors?” in such a way that everyone immediately knew to whom it was apropos? – Now, for example, until he comes in . . . It’s just that he’s late, just about everyone’s sat down already, he’s the last . . . It’s just that he’ll have to get through the entire dining room, through the brambles of the sudden quieting, if not along the black ice of Mr. Steel’s unctuous voice, he who will not take him into account . . .

Someone passed by. The late boarder jumped back, supposing that he was standing in the way, but so clumsily that he rammed right into the person he’d been dodging. That was Zinaida, carrying the soup. He swerved again, but just as ineptly; he inadvertently ended up right against the door. Zinaida reached for the handle.

“Here, hold that! Now wait a second!”

She opened the door, went in, and slammed the door shut with her foot.

He turned red, puffed up like a rooster. Fury was strangling him so much he had to open his mouth. But he didn’t get anything out of it, not a peep. For he beheld a kind of large open space that he had to get through alone, without help, at the mercy of malicious stares feasting on his dizziness, and he beheld that it could no longer be helped. He was so unconditionally walled up in that “I can’t not walk into the dining room” that he inadvertently recalled the first time he had to scramble out of the trenches. Now there wasn’t even an order or necessity or duty. But who says there isn’t duty? Only it’s the duty of Newton’s apple: to fall to earth . . .

Yet when he reached for the handle the door opened again, and he was face-to-face with Zinaida.

“Excuse me, please!” she said, as if underscoring the sudden quiet that had broken out from the dining room in her wake. But she closed it behind her so slowly that he wondered, he wondered whether that closing wasn’t the mournful and ashamed retraction of the rude “Excuse me, please” a moment before, and when he looked up he noticed that Zinaida was not only not avoiding his eyes, but it was rather as though she had been waiting them out. They were standing there saying something to each other that neither of them understood. He, nevertheless, knowing that they were saying something to each other that he would never hear again, that no one would ever displace with anything, and that they could both deny later. Then she looked him over slowly from toe to head, and when she arrived at his eyes a simpleton’s smile took up residence on her lips.

“Oh, it’s you? Would it be a bother if you were to take your lunch in the kitchen? You’re the last, there are no more empty places.”

“That’s not true.”

She didn’t lower her eyes; on the contrary, she set them on him. (Someday, later on, he’ll tell himself, “she set her eyes on me still more Christianly.”)

“No, it’s not true. But there I’ll lay your table myself. Nice. And you’ll get more.” She took him by the hand and led him, submissive. But at the threshold she stopped.

“For Christ’s sake, why didn’t you smack him one?”

It sounded different from before. No longer just contemptuous; helpless.

____________________________________________________________________

RICHARD WEINER (1884 – 1937) is widely considered to be one of the most important Czech writers of the 20th century. The author of several works of poetry and prose, his writing was suppressed during the Communist period and only became recognized for its importance after 1989.

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

BENJAMIN PALOFF is a professor of Slavic languages and literatures at the University of Michigan. He is the translator of several works of prose and poetry and the author of a book of poetry, The Politics. He is the recipient of fellowships from Poland’s Book Institute (2010), the National Endowment for the Arts (2009-2010), the Michigan Society of Fellows (2007-2010), and PEN America, and he was a poetry editor at the Boston Review for seven years.

____________________________________________________________________

Read more work by Richard Weiner:

An essay on Weiner by translator Benjamin Paloff in PEN America

A novel excerpt in PEN America

A novel excerpt in 3:AM