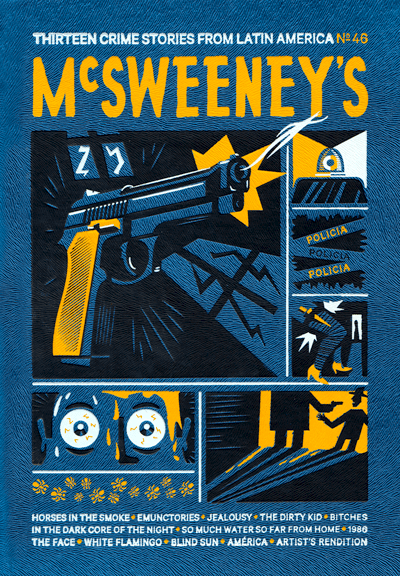

McSweeney’s Issue No 46

Edited by Daniel Galera

McSweeney’s

271 pgs.

If you start reading McSweeney’s Latin American Crime issue expecting something resembling the Scandinavian crime fiction so much in vogue, or even American or French detective stories, hardboiled or otherwise, you will find a very different book indeed. Of course, there are echoes, borrowings, but in most respects they are merely tangential. These authors are writing from a different universe altogether, one more closely resembling that of Kafka than where a Jo Nesbø or Raymond Chandler sends a detective out into the murky streets to solve a crime.

Your typical crime fiction is told from the point of view of a detective, which isn’t the case for a single one of these stories. The closest we get is Santiago Roncagliolo’s “The Face”, in which a judicious assistant prosecutor carries out the investigation of the murder of one of Peru’s most beloved singers only because the policemen assigned to the case is so hopelessly incompetent or corrupt that he hardly goes through the motions of trying to find her killer. In Juan Pablo Villalobos’s “América” we get a glimpse of the ruthless Mexican police force as part of the corrupt political machine and the toll it takes on people’s lives. One of the points of the story though is that the police are just bit players in a murderous charade, too low and slavish to qualify as villains let alone any kind of focus for the narrative.

Nor do the stories partake of the literary tradition of delving into the darkly fascinating world of criminal psychology, for the truth is, despite the anthology’s title, it isn’t crime that preoccupies these writers, but justice, and how inaccessible it is. The characters hoping to identify a murdered child in a squalid Buenos Aires neighborhood or to find a missing transsexual prostitute they fear was beaten and killed by the Havana police, do so with the same futile lunges toward inaccessible justice as Joseph K.

The stories are never Kafkaesque in the clichéd sense of writers trying to dip into what they perceive as Kafka’s literary repertoire. It’s not a matter of art imitating art, but as if the Latin American reality depicted here conforms to the absurd, torturous scenarios that were given their artistic form and name a century ago by the great writer from Prague.

And while the reality that Kafka supposedly “prophesized” took the form of a totalitarian nightmare and a bureaucracy run amok in Eastern European life (and fiction), the form of Kafkaesque reality in the Spanish-speaking Americas is different, at least through the eyes and pens of these writers; no less violent, though its violence is more personal – a joyful rape and murder as opposed to systematic extermination. There also tends to be a lot more booze, cocaine and sex, yet the enjoyment of these is rarely free of the whims of sadistic authorities.

In some of the stories the characters find themselves imprisoned unjustly, arbitrarily, and without redress. We first meet the main character of Rodrigo Rey Rosa’s “1986”, known only as the hedonist, in what is essentially a jungle prison camp run by a brutal sadist called the Cowboy. The camp is peopled by the wayward sons and daughters of wealthy Salvadorans, Guatemalans and North Americans who thought they were sending their children for some tough love rehab but end up condemning them to the caprices of an insane cult leader as free from any legal oversight as Kurtz was in his own jungle haven.

In “Emunctories” by Rodrigo Blanco Calderón, a fairly ordinary series of events (translator returns to Venezuela after many years, gets drunk at literary event, goes home and sleeps with the journalist that interviewed him, takes a shit in her toilet) leads to circumstances that make Joseph K’s arrest appear to be the pinnacle of sensible law enforcement (no water in toilet, puts shit in designer bag to bring it outside and dispose of, bag stolen by motorcyclist, on next day’s visit to imprisoned friend gets confined by policeman who was motorcyclist that stole said bag). What follows is another story of a character imprisoned for little or no reason in a harshly oppressive world.

Yet while the oppression is ever-present these are the opposite of social realist stories. The stress lies elsewhere. In different ways the most effective stories here play with the dynamic of the question that arises with each and every horrific situation depicted: “Is this real?”, which is a moral question (“Can this really be happening in a civilized society? This is terrible!”) and an artistic one (“Are these events actually happening, or just being imagined? Is this realism or surrealism. This is incredible!).

Other writers take the issue of injustice into historical and social dimensions. In Joca Reiners Terron’s “Blind Sun”, a Polish insurance assessor whose grandfather had been killed by the Soviets in the Katyn massacre has to go to the site of a similarly inhuman massacre of poor Brazilian laborers that he knows will also go unpunished. Brazil’s social strife is also dealt with by Carol Bensimon in a powerful and surprising story set during violent street protests. If ever a book exploded the prejudices associated with the term crime fiction as being too restrictive, this is it.

— Michael Stein