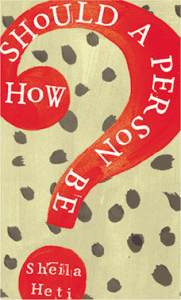

How Should a Person Be?: A Novel from Life

by Sheila Heti

Henry Holt and Co. (2012)

320 pages

“Where have we come from, where are we going? The answers begin in our past.” -- Ray Bradbury's original script for Walt Disney's 'Spaceship Earth' ride at Epcot Centre.

How should a person be? How should we act? Should we strike an aloof pose or commit to full engagement in all our surroundings? Does our writing matter? Our lives? Our careers? Should you be cordial to those people you don’t like or does that make you the worst kind of phoney? Is it okay to fuck because we are lonely and not because we are in love? Is it narcissistic and selfish to try to live as an artist?

Sheila Heti’s titular question, “How Should a Person Be?”, and all of the questions spiralling out from it, will be familiar and comforting to many. Such questions tackle the essence of the anxiety we feel as we grow into who we are. Which is why the central question of the novel is not so much how should we be but, perhaps more importantly, how do we become: “I know that inside the body there’s just temperature. So how do we build ourselves?” Questions like these comfort all the more if you live in a celebrity- and image-conscious culture that seems hellbent on making you feel bad for not being famous.

Presenting a fictionalised portrait of herself, Heti’s “Sheila” is a young artist who has gotten a small commission to write a play that she’s struggling to complete. She drinks too much, smokes too much, hangs out too much, sleeps with an excellent lover and becomes semi-obsessed; she moves from Toronto to New York but still can’t write the fucking piece. Yet in her writing about the her inability to write, she produces a novel that feels so real that at times you can actually feel the pinch of Sheila’s shoes.

Sheila’s failure to get her act together and write her commission is a source of true stress, embarrassment, frustration and also perverse pride. “You can admire anyone for being themselves,” Heti writes of this dichotomy, “It’s hard not to, when everyone’s so good at it. But when you think of them all together … how can you choose? How can you say, I’d rather be responsible like Misha than irresponsible like Margaux? Responsibility looks so good on Misha and irresponsibility looks so good on Margaux. How could I know which would look best on me?”

Yet, while these questions all still feel very much a part of our existence, there comes a time when they stop being so urgent and become a bit less entertaining. Even the most empathetic reader will want to slap Holden Caufield at some point and tell him to get over himself. Part of life is simply getting used to the fact that we make mistakes, have bad habits, waste time, and are guilty of squandering the meaningless life we’re lucky to have.

So, as Sheila proves unable to do her work or make a concrete decision, as she hurts her friends and moves to another city, her worries and misadventures grow worryingly awkward and even frustrating to read. The lure of identification with Heti’s doppelgänger becomes a kind of trap, transforming nostalgia for a frustrated past into actual frustration. It’s a clever move and feels a bit like being tricked into sharing an apartment with your teenage self. And yet, because the author and the narrator share the same name and much of the same history, it can difficult to separate your annoyance with the character from the author, who has made such a perfect foil of herself.

Heti has written a character that anyone who has asked, “How should I be?”, ought to understand and will probably want to argue with in a dingy bar late into the night, whiskey glasses in hand. Our curiosity about what it means to be alive is so essential to who we are that it’s a question that’s never going to be answered easily. So we forgive Sheila the character for examining her navel and her friends’ navels, and trust Heti the author to lead us into and through her own obvious frustration – or at least bemusement – with Sheila’s endless procrastination, until the novel fully opens up and Sheila becomes a fully-realized reflection of her reader.

— Ryan Van Winkle