The Median Flow

The Median Flow

Poems 1943-1973

By Theodore Enslin

Black Sparrow Press

170 pages

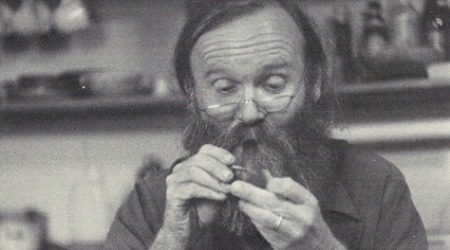

The poet Theodore Enslin (1925-2011) was above all a musical poet. Music, in terms of song and notation, informed his poetry always. Having studied composition with the French composer Nadia Boulanger, Enslin declared “I like to be considered as a composer who happens to use words instead of notes.”

The concept of words-as-notes, as well as the idea that the poem on the page bears more than a visual resemblance to a musical composition, is the lithe foundation on which Enslin based his writing. Associated with Cid Corman and the Objectivists, Enslin is one of the most clearly musical poets to emerge in the US after World War II. His poems are usually short lyrics that utilize the space of the page in a manner that emphasizes the shape, sound, and meaning of each individual word:

There is this air–

a temper

which is tempered

clearly and clean,

a bearing on entrance

and departure–

perhaps known at the beginning,

and then

not conscious–

a manner of saying.

At times, Enslin borrows directly from music, as in “The Diabelli Variations,” a cycle of poems that takes its name from a classical series of piano exercises. But Enslin’s poetry is not about music, exactly. Instead, like Robert Creeley, he is a great poet of domesticity. Numerous poems in The Median Flow are not just about the intimacy of lovers and family, but actually enact that intimacy in their easy precision and tranquil tone. “For Susan” is one example:

I wonder, always,

what we have to say to each other.

After the first conversation

the ground is broken and left.

After an understanding

what do we know?

Words find themselves,

flow into each other,

but incompletely.

What is left is

is

a relationship.

It is different.

One of the most intriguing works in this collection is “New Sharon’s Prospect,” a thirteen-page collection of poetry and prose about a family in rural North New England. Enslin prefaces the poems with a bit of history:

A few years after the Pilgrims had founded Plymouth Plantation and the Puritans had settled Boston and Salem, there were a number of books written about this ‘new’ England, usually by men in the employ of English merchants, to attract settlers to a land soon to be exploited. One of the best of these books was William Wood’s New England’s Prospect, a handbook in prose and verse…

Enslin’s “Prospect” is a revision of this old form, portraying the hard-scrabble life of farmers with whom he worked. Throughout, he brings his linguistic precision and focus of detail to bear on the personalities of this unusual family and the minute particulars that make up their life.

Old bones,

hair combings,

bent matches,

tinfoil,

leavings

all heaped in with ashes.

Kitchen stove crusted

over.

Have this

and know:

Untidiness is the essence of despair.

In lesser hands, the family would become simply a symbol of a way of life that is disappearing. Enslin grants them their own dignity, excavating moments of profundity from the every day. In “The Old Lady with Her Girls,” he writes:

Sometimes it must be

lonely to the point of a scream

they have in silence–

sitting–talking aimlessly–

sewing–

or just trying to keep warm

by little fires

the men haven’t time to tend.

Even at its most musical, Enslin’s poetry keeps fidelity with the things of this world. His is a rural poetry that privileges objects over ideas. The poem “Witch Hazel” seems to profess this preference for the world of man and nature over abstraction:

This:

That is my straight-flying fury.

And not this:

The dead bone of poetics buried

under sacramental clouds

of sleep or of wine, or too much

awareness of the things that are not there:

Ghosts.

I will make directly through

the woods where the early and late

witch hazel keep blossoms in a long season.

Cut me a switch! […]

Cut me a switch to whip old ghosts

through sunsets to the morning.

Enslin published more than 50 collections of poetry between 1958 and 2004. The Median Flow gathers the strongest work from his early period. There is much to enjoy in this collection of finely tuned poems by a rewarding poet from outside the clamor of the American poetry establishment.

–Stephan Delbos