The Marvel of Biographical Bookkeeping

The Marvel of Biographical Bookkeeping

By Francis Nenik

Translated by Katy Derbyshire

64 pages

Readux Books

Francis Nenik’s formally inventive epistolary novella The Marvel of Biographical Bookkeeping is so arresting, so evocative, and so emotionally invested that you want it to be real. In fact, even readers intimately acquainted with the book’s two protagonists, the all-but-forgotten British poet Nicholas Moore, and the schizophrenic Czech exile poet Ivan Blatný, may believe that this book is a work of non-fiction. This is due largely to Nenik’s introduction, in which he describes finding the poets’ mutual correspondence in the London Metropolitan Archives, in a collection consisting of “a large number of documents on the subject of mental illness and mental disability.”

Meticulously researched and lyrically arranged, The Marvel of Biographical Bookkeeping first illuminates the uncanny parallels between the lives of Moore and Blatný. The book opens with narratives of each poet’s life, printed on facing pages, in regular type for Moore and italics for Blatný. It begins:

“When the critic George Steiner looked through the entries for the Sunday Times Baudelaire translation competition he was judging in 1968, he was no doubt a little surprised. Someone had submitted more than thirty versions of the same poem.

When the journalist Jürgen Serke came across a slim man with a small cut on his freshly shaven cheek in St. Clements Hospital in Ipswich in 1981, he was no doubt a little surprised. The man had been declared dead more than thirty years previously.

That someone was Nicholas Moore, an aspiring English poet during the 1940s, who had somehow disappeared from the radar at the end of that decade and had not made a reappearance since.

That man was Ivan Blatný, an aspiring Czech poet during the 1940s, who had absconded from his delegation on a trip to London in 1948, stayed in London and then disappeared.

That is, Nicholas Moore had never really disappeared…

That is, Ivan Blatný had never really disappeared…”

After this introduction, Nenik gives a few words about his “research methods,” then presents the poets’ correspondence. Of the 14 letters included, six are from Blatný. Anyone familiar with his extraordinary and tragic life and work — escape and exile from Czechoslovakia; pronounced dead on Czech radio by the communists; committed to insane asylums in the UK in the last decades of his life due to worsening schizophrenia; the countless poems that were destroyed by nurses; the ultimate recovery of his work and publication by Josef Škvorecký in Canada; the late poems that stretch the linguistic possibilities of poetry in Czech, English and German all at once — will read avidly.

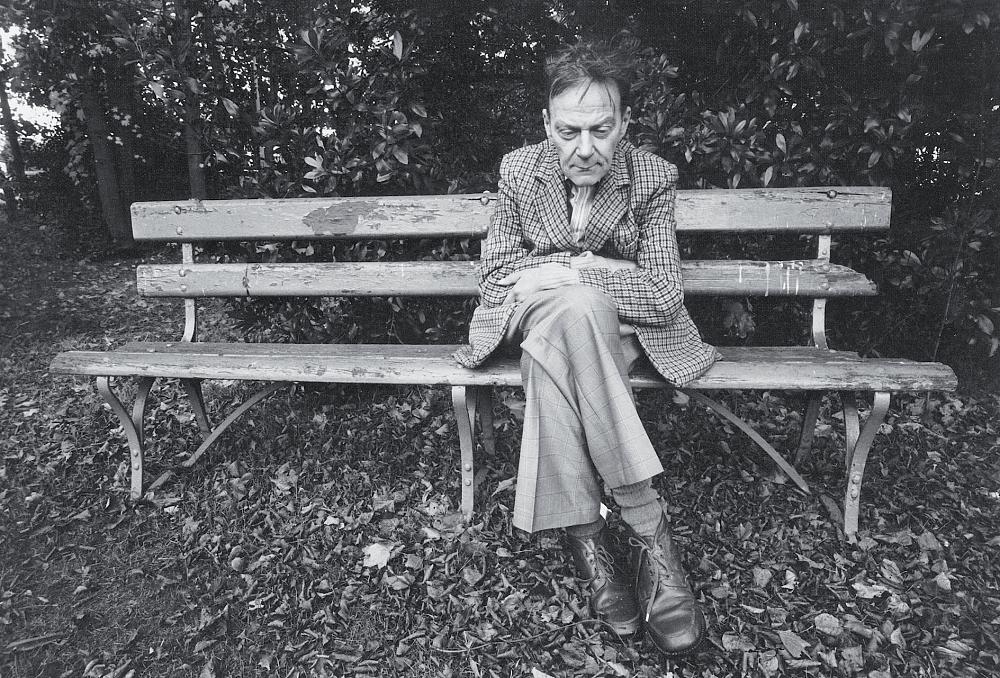

Moore’s life was similar in its early promise and long decline. A respected young British poet in the 1940s, Moore was abandoned by wife and family in 1948 and thereafter lived in obscurity, poverty, and increasingly ill mental and physical health. Writing continuously without publishing, he would become a shadow whose biography would be a tale of warning — against what? — if anyone still spoke about him.

Nenik convincingly illustrates the strange parallels between the poets, including their fateful years of 1948, their lives in southeast versus northeast London, their late discovery by younger acolytes in obscurity, and more. The letters offer little insight into the poetry of these men, nor are they intended to. Rather, they are something like poems in themselves.

Even when the poets exchange something as banal as bibliographies, the placement of these in the text draws scrutiny, and not only provides a record of lesser-known or forgotten books, but creates a kind of poetry of titles. Bereft of complete poems to exchange, the poets exchange one-line creations. Moore’s include The War of the Little Jersey Cows, and Recollections of the Gala. Blatný’s include Melancholické procházky, and Jedna, dvě, tři, čtyři, pět. Of the last, Moore writes:

PS: I have started learning a little Czech. I have already managed to translate the title of one of your books. It is called ‘one, two, three, four, five’. And this morning I thought of this:

Five words make a sentence.

Four words make four

Three make three

Two two

One?

One word makes the next.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given its protagonists, The Marvel of Biographical Bookkeeping‘s closest bibliographic ancestor is a book of poetry. Jack Spicer’s After Lorca, published in 1957, purports to be Spicer’s translation of Lorca’s poetry, and also includes several letters from the San Francisco poet to the Spanish poet. The icing on the cake, and the giveaway, is an introduction from Lorca, written two decades after he had been killed. If it is literary scholarship, it is of the most mischevious sort. More accurately, it is creative historicism, an homage that — if only subconsciously — attempts to elevate the writer to the level of his subject.

Nenik treats his subjects lovingly. His erudition and his keen sensitivity expose strangely significant details in the lives of Blatný and Moore, but what is more valuable is that this book becomes a testament to the icon of the writer in exile. Humanizing the absurd struggle of commitment to creativity in the face of monolithic obscurity, The Marvel of Biographical Bookkeeping is both stubbornly hopeful and soberly realistic. It is, in short, a fascinating little book that reveals the tragic aftermath of triumph.

Ultimately, the question of whether or not this correspondence is real is beside the point. Nenik is an original writer whose keen imagination and chameleon-like style have combined to create a little golden thorn of a book, one that speaks profoundly about its historical characters and the human condition. Find it and read it.

–Stephan Delbos