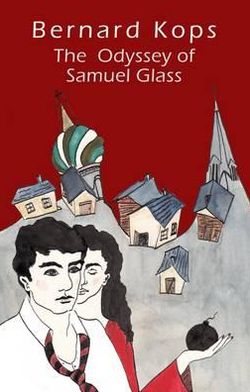

The Odyssey of Samuel Glass

The Odyssey of Samuel Glass

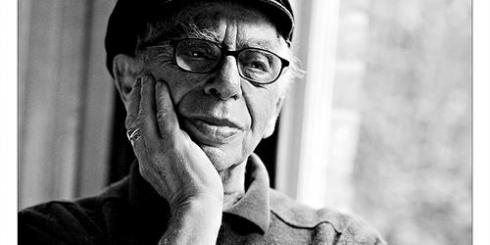

By Bernard Kops

David Paul Publishing, 2012

272 pages

In 1881, the notorious anarchist organization Narodnaya Volya (The People’s Will) assassinates the tyrannical anti-Semite Tsar Alexander II of Russia, the flames of murderous pogroms sweep through the city of Vitebsk and its surrounds, and a Jewish boy from Muswell Hill in 21st century London is rescued by the banned Yiddish Jericho Players company — wait, what?

Anglo-Jewish poet Bernard Kops, in his great new Holocaust novel steeped in rhythms and rhyme, tells this fantastic and entirely believable tale with warmth, humor, empathy and depth. The Odyssey of Samuel Glass pulsates like the finest fictions from the immortal pen of the Soviet-Jewish master Isaac Babel. It also offers budding writers a master-class in poetry.

The novel’s plot is about the present. Its characters are contemporaries whose forebears struggled through the great European migrations. Like a fateful refrain, the menacing sound of Holocaust cattle-trucks clanging through the frozen Russian terrain, and the crying of the people inside, are audible throughout the narrative. But this is also a very funny coming-of-age story.

Samuel Glass is probably the only lad in all poetry and fiction who manages to shed his skateboard as well as his innocence several times in succession. Our adventurer turns up in 19th century Vitebsk, the town of his forebears, to confront his destiny, but finds himself trapped in the wrong country and the wrong century of a confusing world. The real world proves even more confusing when the sounds of the Holocaust horror follow him all the way back to the idyllic Thames Valley of London.

Most of us know much about Vitebsk in Belarus, and know much more than we know that we know. Images of its huddled streets, gorgeous women and iconic roof-top fiddlers populate the walls of our homes and museums, the great ceiling of the Paris Opera, and the windows of the Reims and Metz cathedrals, as well as the palace of the United Nations. For this was the hometown of the Hasidic painter Marc Chagall (1887-1985), and the scene of dreadful World War II atrocities which spared just 118 survivors out of a civilian populations of 170,000. The Tate Gallery of Liverpool has just assembled a landmark exhibition of Chagall’s work, and Penguin has reissued its outstanding 2008 biography Chagall: Love & Exile by Jackie Wullschlager.

Kops’ world, like Chagall’s, is centered around wise, passionate and magnetic matriarchs at the peak of their power, and surrounded by weaker men, whores and witches. One such matriarch is Lisa, Sam’s widowed mother, who is about to embark on a love affair just a year after the untimely death of her beloved husband, Sam’s father. Another is Sarah, Lisa’s equally young and desirable great-great grandmother, who summons our heartbroken hero back into history to assassinate the tsar. Unsurprisingly, the tyrant is less loathsome to Sam than Lisa’s chosen David and Sarah’s new husband Akiva.

Many writers familiar to any budding North London poet pop up in the story unexpectedly and always on cue. Sam meets a best-selling author named Anne Frank who wonders why he had to run away from home, since “mine,” she recalls, “ran away from me.” Lovers of freedom like Lorca and Shelley stroll through the brutalized Russia that is soon to come under the yoke of the Soviets. Sam, who has never experienced a single act of anti-Semitism on Muswell Hill Broadway, watches T. S. Eliot climb off his pedestal to seek out the Jews, as he put it, “underneath the piles.” Shakespeare even helps out when the protagonist must eventually sing (literally) for his supper.

Kops hails from the now bygone era of destitute European Jewish immigrant settlements in East London, populated by people who sheltered there from the Holocaust. Sam’s Russian Odyssey is full of autobiographical turns.

This 87-year old author is extraordinarily prolific and, at long last, commercially successful. The 2010 publication of his collected poetry This Room in the Sunlight (David Paul Publishing) was a major event for English literature. He has also issued six previous volumes of verse, more than 40 plays, and two autobiographies. He was first catapulted to world fame as an originator of Britain’s new wave, “kitchen-sink” theater with his 1958 play The Hamlet of Stepney Green.

All of Kops’ writing is rooted in poetry, which explains his ability to make his prose throb with passion, as famously done by the short story writer Isaac Babel (1894-1940) in his classic 1920s Russian collection Red Calvary. How does Kops do that in English? Let us enter his workshop.

Formally minded English poets know that in any copy prepared for public recital, the language demands a pause or at least one unstressed syllable, and does not tolerate more than two unstressed syllables, between two stressed ones. A writer ignoring this may expose the text to awkward stresses of pronunciation or unintended pauses in the performance. Properly used, this formula gives us something like blank verse, the most versatile traditional meter in the language. Its commonly employed five-footed line easily lends itself, depending on the mood of the text, to the expression of anything from light musings to cutting satire or pulsating tension.

In the following example chosen almost at random, a passage of Kops’ prose about the spread of panic at Vitebsk railway station has been lightly edited to turn it into vibrant descriptive poetry:

A long queue of ragged, silent and lifeless humans

were shuffling forward, one shoe at a time,

everyone trying to get away from Vitebsk.

The Red Rabbi sniffed… checking the atmosphere:

“I fear there is pogrom in the air.”

“There is always a pogrom in the air and more often

a pogrom on the ground,” Akiva retorted.

The creatures in the queue seemed barely able

to rub two kopeks together. Where were they off to,

and why? As they approached the ticket hatch

some urgent whispers started to circulate.

The voices of the lumpen stragglers were

morose and suddenly fearful. “Did someone say pogrom?”

An old hag cackled: “I see it with my own ears…”

A toothless man muttered: “I’ve heard it with my own eyes…”

“When, WHEN?…” “Anytime you like… Tonight! Tomorrow

or yesterday!…” But, “It is all a tall story,”

uttered a heavily pregnant Jewish dwarf.

Now consider Kops’ unedited prose below, describing a real pogrom raging amidst a theatrical performance:

Chaos was smiling on his rostrum, conducting the scene. The hall was alight and the crowds from outside rushed in with burning torches. The cast huddled together on stage. The audience was a tangled, screaming, unbelieving crowd.

And the mob went in amongst them.

“Death to the Yids. Pogrom! Pogrom! You bastard Jews. Christ murderers. You’re finished in this country.” And daggers and breadknives were doing their job, a flashing flood; and blood was fountaining, pouring down and hammers were crashing, and smashing and nightmare was king.

The hall ignited and the slavering flames licked at the bundle of actors upon the stage…

And down in the hall, peasants cried and fought each other and tore at each other desperate to get outside.

“Death to the Yids! Death to the Yids.” The chorus continued outside.

“We’re finished. We’re finished. God help us. They are burning us. They are turning us into smoke.”

They cried and a vacuum of silence rushed in from the world; and the woman with her baby was sliding in the blood where the dead lay, gushing their innards; the baby still sucking the breast, and as she sang softly a lullaby. “Sleep my baby sleep. Roshinkers mit mundelan, almonds and raisons, sweet and bitter, sleep my baby sleep.”

As a boy, Sam had slipped into the past to get away from home; as a man, he must seek his future aboard an immigrant ship with the touring Jericho Players dreaming of their own, permanent Yiddish theatre on the old Commercial Road of London. In real life, several Jewish theatrical companies from Eastern Europe were badly received in 19th century England, but they travelled on to set up the American film industry in Hollywood. The British film industry was created only during Kops’ childhood by the poets, actors and directors brought together by the famous Jewish-Hungarian Korda brothers.

Before he is allowed to return to his prosperous, modern reality, Sam must still experience the poverty of Kops’ native East End of London. Despite the squalor and degradation, Sam feels almost comfortable there. In a moving nod to his own, deprived childhood, Kops observes that “compassion and caring was still alive in the shtetl that was the old East End.”

–Thomas Ország-Land

____________________________________________________________________

THOMAS ORSZÁG-LAND is a poet and award-winning foreign correspondent who writes from London and his native Eastern Europe. His next book will be THE SURVIVORS: Holocaust Poetry for Our Time (Smokestack, 2014).