Since the 1980s, numerous American poets have addressed the AIDS crisis, bringing imagination, craft and witness to their personal experience as well as mourning the deaths of friends and acquaintances.

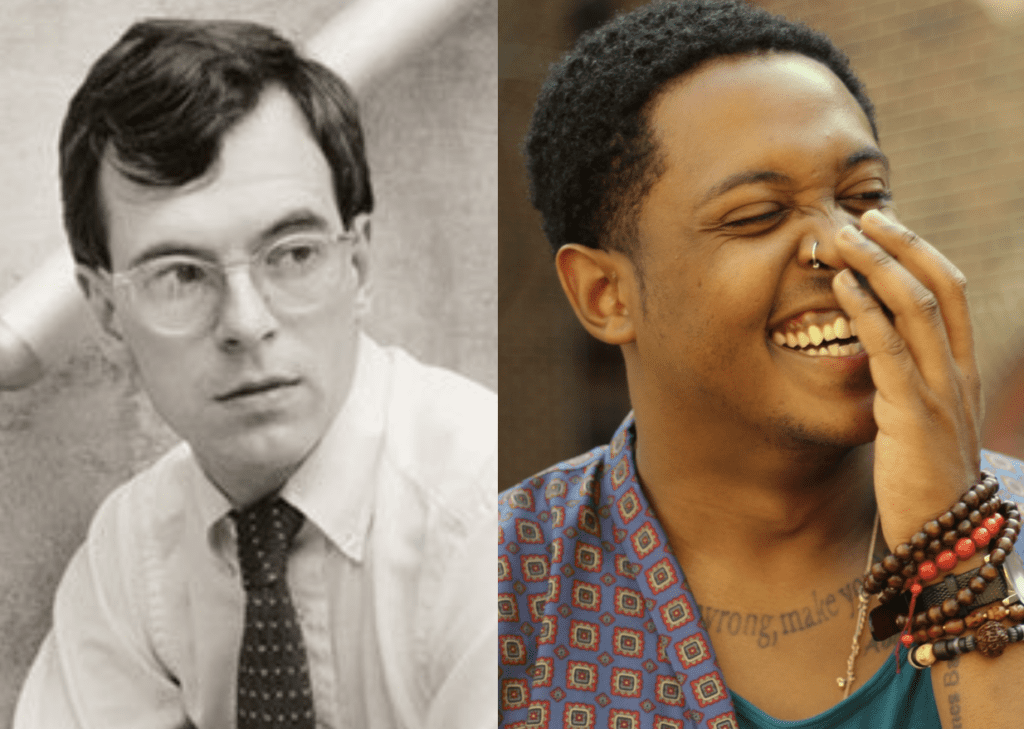

Comparing the poetry of Tim Dlugos, who died of AIDS in 1990, and Danez Smith, who is HIV+, clarifies the evolving relationship between American society and AIDS, and shows how two poets follow truth through taboo when writing about this ongoing pandemic.

Dlugos’s poem “G-9,” portrays the hopelessness of an AIDS diagnosis in the 1980s and mourns the tragic losses of his generation — while finding peace in memorializing his own life as he approached death. In contrast, Smith’s poetry reveals what it’s like to live with HIV, managing the illness indefinitely thanks to new medications.

The evident evolution of the relationship between poet and illness in the poetry of Dlugos and Smith is due to developments in medicine, poetry, and public perception.

A Timeline of Illness

The first written mention of what would come to be known as AIDS appeared on May 18th, 1981, when an LGBT newspaper, The New York Native, published an article entitled “Disease Rumors, Largely Unfounded.”

In 1982, the CDC published an article describing a handful of cases of lung infections in young, otherwise healthy gay men in Los Angeles, two of whom had died by the time the article was published, and three of whom died shortly thereafter. The following month in San Francisco, an article on “Gay Men’s Pneumonia” urged gay men experiencing shortness of breath to see a doctor.

In 1983, “New Homosexual Disorder Worries Health Officials” was published in The New York Times. This was the first public mention of “GRID” or gay-related immune deficiency, the original name of HIV or AIDS. This name increased the misconception that AIDS only affected gay men. Later in the year, the newspaper published its first front-page article on AIDS.

In September 1985, President Reagan finally mentioned AIDS in public for the first time, calling it a top priority and rebuffing accusations that his administration had not taken it seriously.

In 1987 Reagan gave his first speech about AIDS and created a Presidential Commission to address the crisis.

In 1992, AIDS became the leading cause of death for American men aged 25 to 44.

Just before 2010, the first medicines combatting HIV and AIDS were tested and released on the market.

Today, more than 30 HIV medications are available. It is possible to control HIV with one pill a day, and early treatment with these drugs can prevent HIV+ people from getting AIDS.

The evolution of the public’s perception of AIDS has coincided with an evolution in treatments. As society and medicine have developed, poets writing about AIDS and HIV have become less threatened, more optimistic, and more comfortable with their diagnosis.

Tim Dlugos: “I hope that death will lift me by the hair like an angel”

Tim Dlugos was born in 1950 and died in 1990, making 1981, the year the first article was published about AIDS, the center-point of his writing career, which included High There (1973); For Years (1977); Je Suis Ein Americano (1979); A Fast Life (1982); and Strong Place (1992), published posthumously. AIDS dramatically altered Dlugos’s life, and his diagnosis, coinciding with the death of many of his friends, deeply influenced his poetry.

Dlugos was a third-generation New York School poet, whom Ted Berrigan called “the Frank O’Hara of his generation.” More recently, Book List has written that “Dlugos’s poetry is autobiographical, of his consciousness and spirit more than of his body and actions. Unlike O’Hara’s, Dlugos’s poetry is often formal, always well measured, polished, without ever seeming labored, and finally more loving than clever.”

A Facebook post published by one of Tim Dlugos’s friends in 2020 provides a more intimate glimpse of the poet:

Tim was whip-smart, sensitive and kind and had a rambunctious chortle (not unlike Phyllis Diller) unleashed when recalling his regular encounters with life’s incongruities. He wrote engaging and accessible poetry and the poet Frank O’Hara was an idol. He had come to New York in 1976 to pursue ‘a fast life’ of poetry and art, love and adventure, friendship and grace — an ideal he returned to throughout his life from boyhood Catholicism through adult AA and on to a path towards the Episcopal priesthood via Yale Divinity School.

Dlugos’s final years were complex: facing his AIDS diagnosis while maintaining sobriety through Alcoholics Anonymous and studying to become a minister — and writing generation-defining poetry. The resulting religious and spiritual overtones in his late work distinguish him from O’Hara, as does his focus on AIDS in several important poems.

“G-9” is one of the last poems that Dlugos wrote, and it takes place in the AIDS ward of Roosevelt Hospital in Manhattan, where he was being treated. Here is the opening of this long poem, which mentions the early AIDS drugs Zovirax, AZT, and Leucovorin:

I’m at a double wake

in Springfield, for a childhood

friend and his father

who died years ago. I join

my aunt in the queue of mourners

and walk into a brown study,

a sepia room with books

and magazines. The father’s

in a coffin; he looks exhumed,

the worse for wear. But where

my friend’s remains should be

there’s just the empty base

of an urn. Where are his ashes?

His mother hands me

a paper cup with pills:

leucovorin, Zovirax,

and AZT. “Henry

wanted you to have these,”

she sneers. “Take all

you want, for all the good

they’ll do.” “Dlugos.

Meester Dlugos.”’

A lamp

snaps on. Raquel,

not Welch, the chubby

nurse, is standing by my bed.

It’s 6 a.m., time to flush

the heplock and hook up

the I.V. line. False dawn

is changing into day, infusing

the sky above the Hudson

with a flush of light.

My roommate stirs

beyond the pinstriped curtain.

My first time here on G-9,

the AIDS ward, the cheery

D & D Building intentionality

of the decor made me feel

like jumping out a window.

I’d been lying on a gurney

in an E.R. corridor

for nineteen hours, next to

a psychotic druggie

with a voice like Abbie

Hoffman’s.

The poem starts with the dream of being at the funeral of a friend who has died of AIDS. The narrator’s exchange with the sneering mother conveys both the hopelessness of the diagnosis and the negative stigma it carried. The early AIDS drugs mentioned seem less effective than hoped. Then the lamp snaps on and the dream is over.

The narrator wakes up in the AIDS ward and begins to describe his time in the hospital with all its interesting characters, like the man who sounds like Abbie Hoffman, the activist and founder of the Youth International Party in the 1960s.

This is a very personal poem but also a very New York poem, mentioning the D&D building in Manhattan, and the Hudson River. At the same time, the inclusion of acquaintances and celebrities is a classic gesture of New York School poetry.

Dlugos’s lines are tightly woven and his language is impeccably measured yet colloquial, elements that contrast his prosody to Danez Smith’s. The poem is anchored to the left, using enjambment and caesura to pull the narrative down the page, making it feel more urgent, an effect that is enhanced by the fact that this poem consists of one stanza pushing down numerous pages.

“G-9” is a sad poem made lighter by ironic humor, which aligns Dlugos with the New York School: often, when the poem conveys a genuine emotion, it quickly turns into a joke. This self-defensive gesture is evident, especially in the first part of this poem, where the narrator conveys difficult details but adds humor by bringing in the wildly bearded Abbie Hoffman along with Raquel Welch.

But towards the end of the poem, the tone shifts from ironic detachment. Starting with the lines “My list of daily intercessions / is as long as a Russian / novel” there is a litany of names, and the narrator talks about his friends and how they came to be diagnosed:

Once I start remembering,

so much comes back.

There are forty-nine names

on my list of the dead,

thirty-two names of the sick.

Cookie Mueller changed

lists Saturday. They all

will, I guess, the living,

I mean, unless I go

before them, in which case

I may be on somebody’s

list myself. It’s hard

to imagine so many people

I love dying, but no harder

than to comprehend so many

already gone. […]

When I pass,

who’ll remember, who will care

about these joys and wonders?

I’m haunted by that more

than by the faces

of the dead and dying. […]

I’ve trust enough in all

that’s happened in my life,

the unexpected love

and gentleness that rushes in

to fill the arid spaces

in my heart, the way the city

glow fills up the sky

above the river, making it

seem less than night. When

Joe O’Hare flew in last week,

he asked what were the best

times of my New York years;

I said “Today,” and meant it.

I hope that death will lift me

by the hair like an angel

in a Hebrew myth, snatch me with

the strength of sleep’s embrace,

and gently set me down

where I’m supposed to be,

in just the right place.

Finally, the poem develops into a mournful but hopeful prayer. It’s a spiritual moment of communion and elegy for Dlugos and his friends as the narrator envisions what will happen when he dies and wonders who will remember him.

By writing the poem, Dlugos created a monument to his friends and himself. Bringing in details from his own life and the lives of his friends, “G-9” ends with an abiding sense of hope and optimism in the face of death.

It’s important to note that for Dlugos and his generation, AIDS was a death sentence. There was virtually no possibility of surviving or being cured. That attitude deeply informs “G-9”, which functions very purposefully as a memorial because Dlugos knew he did not have much time left.

Danez Smith: “Why not make the blood a business?”

Dlugos’s relationship with his illness contrasts with the poetry of Danez Smith, who was born the year before Dlugos died. Dan Chiasson has described Smith’s work as “enriched to the point of volatility, but [paying] out, often, in sudden joy. Smith’s style has a foot in slam and spoken word, scenes that reach people who might not buy a slim volume of poems. But they also know the magic trick of making writing on the page operate like the most ecstatic speech. And they are, in their cadences and management of lines, deeply literary.”

Smith’s collection, Homie (2020), has been well received by critics at major publications including The Guardian: “Homie is deeply moving and funny, with poems such as ‘all the good dick lives in Brooklyn Park’ combining a story about a booty call with the tragic decline of a lover dying from an unnamed illness.”

This description can be applied to many of Smith’s poems, including “strange dowry:”

bloodwife they whisper when i raise my hand for another rum coke

the ill savior of my veins proceeds me, my digital honesty about what

queer bacteria has dotted my blood with snake mist & shatter potions

they stare at my body, off the app, unpixelated & poison pretty flesh

they leave me be, i dance with the ghost i came here with

a boy with 3 piercings above his muddy eyes smiles then disappears into the strobes

the light spits him out near my ear, against my slow & practiced grind […]

for five songs my body years of dust fields, his body rain

in my ear he offers me his bed promise live stock meat salt lust brief marriage

i tell him the thing i must tell him, of the boy & the blood & the magic trick

me too his strange dowry vein brother-wife partner in death juke

what a strange gift to need, the good news that the boy you like is dying too

we let the night blur into cum wonder & blood hallelujah

in the morning, 7 emails come: meeting, junk, rejection, junk, blood work results

i put on a pot of coffee, the boy stirs from whatever he dreams

& it’s like that for a while. me & that boy lived a good little life for a bit

in the mornings, we’d both take a pill, then thrash

Smith’s style is very different from Dlugos, whose tightly bound lines keep pulling themselves back to the left side of the page. Smith uses more space: their lines are longer and there is little enjambment as Smith favors minimal punctuation and capitalization. Here, those formal choices frame a narrative about being HIV+ and meeting someone at the club, feeling obligated to tell them, and then finding out that they’re HIV+ as well, so a risk-free relationship can happen.

In the second half of the poem, the narrator realizes, once the other person confirms he is also HIV+, that this illness is a “strange dowry.” The poem then presents a condensed explanation of how the narrator and his romantic partner got HIV. There is a physical and almost romantic exchange before explaining that in the mornings, “we’d both take a pill, then thrash,” presenting an insight into how it is to live with HIV while having the medication to control it.

This evolution in attitude was also reflected in the timeline at the beginning of this essay, which highlights the development of AIDS medications, and suggests how impossible it would have been for Dlugos to imagine living with AIDS and continuing to have sexual relationships.

It’s a stark contrast: for Dlugos, AIDS meant death. For Smith, HIV is something you can live with. And this is evident throughout Smith’s work, including the poem “sometimes I wish I felt the side effects:”

but there is no proof but proof

no mark but the good news

that there is no bad news yet. again.

i wish i knew the nausea, its thick yell

in the morning, the pregnant proof

that in you, life swells. i know

i’m not a mother, but i know what it is

to nurse a thing you want to kill

but can’t. you learn to love it. yes.

i love my sweet virus. it is my proof

of life, my toxic angel, wasted utopia

what makes my blood my blood.

i understand belle now, how she could

love the beast. if you stare at fangs

long enough, even fangs pink

with your own blood look soft.

This is a poem about coming to terms with being HIV+, and to do that, you need to know what you have and how you got it, something that was more difficult when Dlugos was writing.

But this poem is very ambivalent about the narrator’s relationship with HIV. At the beginning, the narrator proclaims: “I love my sweet virus.” Later, the narrator says “It felt like I got it / out the way to finally know it / up close, see it in the mirror,” which conveys a sense of acceptance. But the emotions are mixed.

“sometimes I wish I felt the side effects” presents one perspective of what it’s like to live with the virus, while Dlugos’s “G-9” shows what it was like to die with the virus. The ending of Smith’s poem is full of anger and regret, but then acceptance arrives in a couplet: “But I only knew how to live / when I knew how I’ll die.” Dlugos makes the same gesture at the end of “G-9,” where he realizes the sweetness of life now that he sees the end approaching — but there, death seems more imminent.

Of course, for Smith, the end isn’t approaching as quickly as it was for Dlugos. Elsewhere in the poem, Smith writes: “it was stupid. silly really. i knew nothing // that easy to get and good to feel / isn’t also trying to eat you.” This is a complex sentence stretched intriguingly across three lines. The meaning of the sentence accrues from not knowing anything, to not knowing anything that easy to get and good to feel, to not knowing that anything that easy to get is also trying to eat you. So, the poem suggests, everything that is easy to get, and good to feel, is also trying to eat you. It’s an interesting and well-crafted utterance.

This complexity is also evident in Smith’s “old confession and new”:

sounds crazy, but it feels like truth. i’ll tell you again.

Maybe i practiced for it, auditioned even, applied.

what the doctor told me was not news, was legend

catching up to me, a blood whispering

you were born for this. i tell you—i was not shocked

but confirmed. enlisted? i am on the battlefield

& i am the field & the battle & the casualty & the gun.

my war is but a rumor & is not war. at the end of me

there is a boy i barely remember, barely ever knew

saying don’t worry, don’t worry, don’t worry, don’t worry.

so now that it’s an old fact, can it be useful?

that which hasn’t killed you yet can pay the rent

if you play it right. […]

many niggas gettin’ paid off the cruelty

of whites, why not make the blood

a business? take it. here’s what happened to me.

while you marvel at it imma run to the store.

my blood brings me closer to death

talking about it has bought me new boots

a summer’s worth of car notes, organic everything.

Reading this poem alongside “sometimes I wish I felt the side effects” clarifies the evolution in the relationship between the narrator and their illness.

The previous poem showed a narrator struggling to come to grips with illness as they went through that ambivalent love-hate relationship with themselves and their diagnosis. That poem wrestled with the diagnosis, finally arriving at acceptance, which becomes a realization that illness is now part of their identity. So there’s a step that’s not fully completed, a step toward full acceptance, but also identification with the illness and making it part of who they are.

The first half of “old confession and new” shows that same ambivalence, but the sentences “blood whispering. you were born for this. i was not shocked, but confirmed” convey the belief that this is the narrator’s destiny.

Whereas “sometimes I wish I felt the side effects” was grounded in the natural imagery of fish, water, and plum, “old confession and new” utilizes the metaphor of a fight in which the narrator assumes the role of the field, the battle, the casualty and the gun. But, ultimately, it becomes clear how the narrator wins that battle, even though the first stanza of the poem ends with the narrator’s inner struggle as they speak to themselves, “a boy I barely remember / barely ever knew, saying, don’t worry, don’t worry…”

An inner struggle. Innocence lost. The boy is no longer there. The narrator can barely even remember the boy he once was.

But the narrator needs the reassurance that comes at the end of the first stanza. And that shows something that may be slightly uncomfortable, as they not only accept the diagnosis but make it part of their brand, a selling point. This is very cynical but knowingly cynical, declaring that they can make poetry out of their diagnosis and that poetry is going to sell and buy them new boots and a new car, better food. From here, the tone and atmosphere of Dlugos’s “G-9” feel very distant.

Two poets, two perspectives

Dlugos was trying to find optimism in his dire situation.

There was no hope of sexual relationships, nor of living beyond his diagnosis. Dlugos thus takes a very stoic stance in “G-9.” He combines that stoic stance with irony, which is self-defensive, but also part of the attitude of being able to laugh in the face of death. In “G-9” Dlugos was writing against the stigma while bearing witness to his own and his generation’s experience. Dlugos’s bravery made poetry like Smith’s possible.

Smith’s poems not only express optimistic possibility, understanding that life with AIDS and HIV is now vastly different, but they also identify with the illness. Smith certainly does laugh in the face of death — all the way to the bank. Their poems refuse to, or do not have to, acknowledge that death is imminent. This reflects how society and our relationship to AIDS and HIV have evolved.

It’s also important to highlight the complexity of Smith’s identity as an HIV+ poet. If a poet writes a poem about living with HIV or AIDS, which still kills hundreds of thousands of people across the world each year, they must realize their access to advanced medications is a privilege. Smith’s stance is bold, declaring their intention to profit from their diagnosis — not just making it part of their identity, but making it part of their brand. That differentiates Smith from Dlugos, and reflects Smith’s position as a poet in late capitalism. For Dlugos and poets of his generation, brashly taking ownership of the illness would have seemed impossible, given the daily drama and tragedy of the AIDS crisis.

Both Dlugos and Smith write about their illness, but Dlugos writes about dying of AIDS, while Smith writes about living with HIV. Reading their work together clarifies the evolving attitude in American poetry alongside society’s gradual understanding of AIDS. Smith’s point of view on HIV could not have been possible during Dlugos’s lifetime. Smith writes about making HIV part of his brand, while Dlugos’s diagnosis was a death sentence, inspiring and necessitating a final reckoning. Smith’s poetry shows how HIV and AIDS have been subsumed into America’s corporate culture of the personal brand. It also shows how poets continue to push into previously forbidden territory, allowing themselves to say more and to take more potentially controversial stances as they witness HIV and AIDS.

It would be a mistake to pigeonhole Dlugos and Smith as merely HIV or AIDS poets. Half of Dlugos’s books were published before his diagnosis, and most of his poems from the mid- to late-1980s do not mention the virus. Likewise, the poems by Smith examined here represent only a small portion of the scope of their work, which sits at the intersection of numerous issues and identities. However, looking at these poets together reveals interesting similarities and differences, and shows just how significantly the approach of American poets to HIV and AIDS has evolved over the last 40 years.

— Stephan Delbos