Scott Kiernan is an artist living and working in New York City. In his video, photo and installation works, electronically synthesized and photographic elements interact to address their own materiality and means of distribution. He is particularly interested in how meaning shifts through stages of translation via technology, speech and syntax.

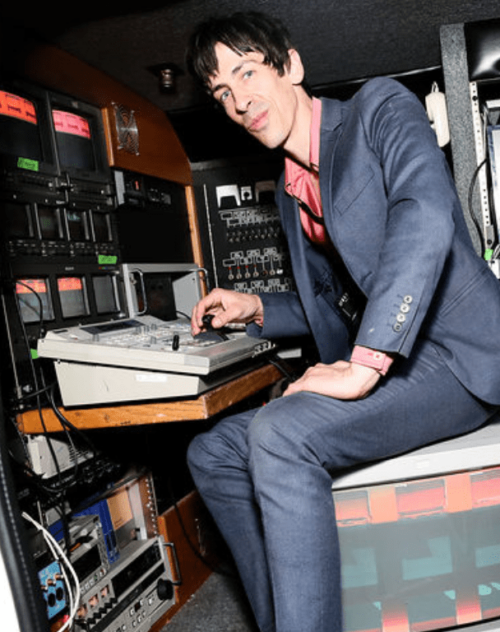

He was founder and co-director of Louis V E.S.P., an artist-run gallery and performance space in Brooklyn, NY (2010- 2012) and now of E.S.P. TV (2011-present), a nomadic TV studio that explores the televisual as a medium for broadcast collaborations. This project also formed UNIT 11, a transmission-based residency program operating from a former ENG van turned mobile electronic studio. Kiernan also directs Various/Artists, a project space in New York City and imprint producing audio/visual releases by artists working across diverse media.

He has exhibited and performed internationally in venues such as Museum of Modern Art, New Museum, Museum of Arts and Design, Swiss Institute/Contemporary Art, Storefront for Art and Architecture, Whitney Museum of American Art, PERFORMA, Harvard Art Museums, P.S. 1, Anthology Film Archives, Mixed Greens, Ballroom Marfa, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, and the Center for International Contemporary Art in Rome.

B O D Y’s art editor, Jessica Mensch, caught up with Scott recently to talk about his work and the thinking behind his artistic practice. For this interview, she was joined by experimental animator and artist, Emily Pelstring. Their conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

B O D Y: I got to know your work first through E.S.P. TV. What was your entry point into live community television?

Scott Kiernan: E.S.P. TV started originally out of a gallery space I was running with my collaborator at the time, Ethan Miller, out of the front half of our loft. The gallery was called Louis V E.S.P. (named as a quasi-abbreviation of a broken neon sign that was given to us). We had been programming monthly gallery exhibitions quite regularly for two years already. But one event we did when TV went digital in the beginning of 2011, when all the TVs were thrown out on the street, was a performance called “E.S.P TV”. It was a performance-based program we could have just had in the gallery like any other, but it had been structured in the form of a live cable-access style show. So, we did it, not being super familiar with the equipment, kind of winging it. I remember our friend at the time, Lee Lichtsinn (long time E.S.P. TV crew member now), was running in the audience with a handy cam hard-wired to the video mixing board. The one-off show led to more until it became the more engaging thing for us, superseding the physical gallery program we had been maintaining. Victoria Keddie became involved early in the project after inviting us to be a part of her media arts festival at the time called INDEX. Soon, she and I really ran with it together and really dug into more aspects of televisual language and transmission through the project.

Our interest in broadcast stemmed from our own focus in performance-based work and signal transmission – things that she was working with in her sound work, and that I was starting to get more into with live analog video again. We were even doing performances together at the time under something called ESP Lab, using the equipment in a very physical, audio-visual way. But there was also a focus on the way things like say cable access, or running a gallery in your apartment could galvanize groups of like-minded people. We were certainly interested in connecting our peers working in different ways as musicians or visual artists or whatever else, and the model of a television show for example could recontextualize the way they are shown together. I remember having that feeling (still do) that a lot of show line-ups or gallery exhibitions tended toward very predictable combinations of people. The live TV format allowed a way to have people work alongside each other who typically wouldn’t be grouped together, and it felt more exciting than physical exhibitions for a while.

B O D Y: I recently rewatched your E.S.P. TV broadcast from the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MoCAD), Live from Detroit (2015). The production is very psychedelic. Performers seem to tilt and sway in time with energetic walls of color, objects and people are surrounded by flickering auras of light, fractured images of the studio audience float in and out frame …

Emily Pelstring: It looks like you’re using video synthesis and feedback alongside digital processing, and most of the imagery is a result of real-time, live generation and manipulation. Can you talk a bit about why you gravitate toward these methods?

Scott Kiernan: Part of this interest in televisual language I mentioned earlier is about a certain distortion of space — where “liveness” becomes a fraught concept when it’s mediated by camera angles and live cuts. That’s true of “normal” TV, let alone when you combine it with some of the ways we might manipulate the video image in real time.

Sometimes that’s the only way to get a certain kind of “result”, but I think for us it was often more that adopting a real-time or “analog” process just takes you to places you cannot predict beforehand. For example, if you work modularly with audio or video (that can be in a digital environment as well), where you’re building your own systems, pathways, networks — you have an intention of where you’re going and can really craft a way to get there but other unpredictable things can happen along the way. And maybe you follow those paths instead and forget your original intention — and this can happen in a way that really doesn’t happen when things are more “in the box”. It sometimes makes you question the accuracy of where you think your intentions lie or originate from.

Emily Pelstring: In your own work, do you also use software alongside analog systems?

Scott Kiernan: Yes, I’ve combined software in the process, often as an intermediary to translate say an analog waveform into data and then back to another type of waveform — sort of an interpolation. In the last couple of installations and performances, this has been used to turn a word-image into a series of points to be re-drawn on a vector display by digitizing it into a sound that can be sampled, recalled and then re-manipulated. If the sound is altered, the image is simultaneously altered because they form an intertwined, observable relationship — I build systems in which each piece influences the other pieces in immediately tangible ways.

Emily Pelstring: As an experimental animator I feel the same way about the permutations and sense of serendipity that comes with a flexible system. It feels like the apparatus is collaborating with you because you’re surprised by what comes out. It feels more like a dialogue, and the results more singular.

Scott Kiernan: I’m not really a machine fetishist or anything, even though I like working in very tactile ways and obviously take an interest in where certain instruments fit in a technological continuum. For example, in Horsetail Falls, nothing involves an analog video signal. It’s done live with hardware. There is something “analog” about that performative process where I’m playing the mixer to make the work, but it’s all digital. However, I am destroying the image of a very analog thing — an old postcard from the turn of the century.

What bothers me is when people disallow the use of older technology simply for being “old” (especially as they don’t in other mediums). And that’s a consumerist impulse – a forced obsolescence. It may be old, but that doesn’t mean it’s not usable. Now, you have more opportunities than ever to create hybrid instruments, hybrid situations or systems, in ways you couldn’t before.

I just came back from a residency at Signal Culture. There’s a lot of things I can do here (in NYC), but they have a Jones Colorizer, and nothing looks like that. Something about the architecture and the components is unique and you can’t replicate that in software. But what’s more interesting though than the thing itself or an effect it creates, is how it can be recombined into a system with other instruments and approaches, how it can lead you to experiment more than replicate the look of something made 30, 40, or 50 years ago.

B O D Y: Is there a conceptual focus to your work that requires analog technology?

Scott Kiernan: Yes. To hybridize an older tool with a contemporary approach is often a central concept. For The Room Presumed for example, the premise begins from a chapter in a book called Tools for Thought from the early 80s by Howard Rheingold — a general survey about the future of computers and technology at the time. One chapter describes people at Atari trying to envision virtual reality, but they don’t have any tools to make an actual “virtual reality” environment yet. So, they almost act it out improvisationally — speaking the roles of the user and the interface. Speech and language are what props up this “immersiveness”. It takes on aspects of gaming or theater in a way. My approach was a bit of an ironic piss-take on what felt like a prevalent overuse of the word ‘immersion’ and how it’s become a lazy, catch-all marketing term for “immersive experiences”. Everything was being called “immersive” for a while (still is to some degree) and it just seemed like salesmanship or laziness. So, I thought, one could think that maybe the most immersive experience possible would defy a need or space for language altogether. Probably a lot of philosophies have thought similarly already … So, to talk about immersion incessantly was odd to me.

So (and this piece is from several years ago) I worked with Ethan Miller on extending this scene from Tools for Thought by using a Machine Learning software trained on the chapter itself and John Perry Barlow’s “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace” (1996). In the end, the ML ended up incessantly describing itself, its everywhere-ness, its all-encompassing immersion — almost in the same hyperbolic marketing speak I detested to begin with. But then something happened where it put phrases together, which read as much darker, more critical, more self-reflexive. Anyway, the concept of combining source material from 35 years ago with the technology of today lent itself to working with a hybrid of analog video tools and contemporary software.

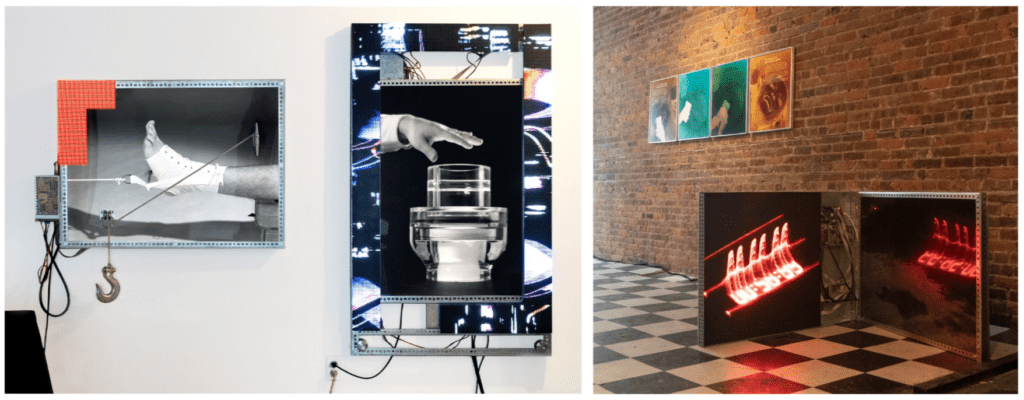

It also interests me that increasingly in video as an art form — sculptural aspects of video are only really appraised on the “backend”. For example, when people think of video having any kind of “sculptural” quality, what they mean is, “Can I project it lots of different ways on a building or a room? They’re just talking about the display mechanism, mapping it, maybe some novel application of using screens — positioning video as kind of cheap and disposable — like how used in advertising.

That it could have any sculptural qualities imbued within its making, is increasingly forgotten about as it’s created more often in closed or opaque software architectures.

B O D Y: Can you talk more about imbuing the video image with sculptural qualities?

Scott Kiernan: That a camera at a certain angle in a certain light catches a specific reflection of another image sent to say an oscilloscope or vector display — and that everything in the room is in a specific balance so that any one gesture can affect the whole. This systems approach — where you have an interdependency between a set of components operating in real-time to make the work, being the “sculpture” …

B O D Y: You use a lot of analog video technology from the 1970s and 80s. As someone whose worked with this technology, depending on how the footage is handled, I’ve noticed this tech can impart a visual timestamp on the image – meaning, the image has a specific feel and quality that recalls the 70s and 80s. How do you navigate this?

Scott Kiernan: I was talking to somebody recently about how people are sometimes more interested in just achieving an effect or look from tools similar to what I may use, than actually experimenting. They want “the VHS look” or some other retro effect and they’re afraid of breaking things, even using software. I think they’re used to having filters and plug-ins to approximate the past. But they’re not trying to put the wrong plug into the wrong thing. There is no wrong plug. That’s what I mean by experimenting, just trying out what you’re not supposed to do, and not just trying to get an effect or look and stopping there.

I just try to work with whatever suits the idea and my process the best. I work with analog and real-time video because I get to certain places that I would not get to any other way. It’s something very in tune with writing for me.

Emily Pelstring: Pursuing an effect is safer, something an ad agency might do, whereas artists have permission to be freer. I was just thinking about the value of tinkering as an artistic method.

Scott Kiernan: Yeah, sometimes you have to say, “What if this, what if that…or… what if this goes WITH that.” And sometimes that doesn’t produce anything that you use, it might be crap, but it also can reorient your thoughts or perceptions.

Emily Pelstring: It seems like there is a conceptual thread you’re following from early video art around the Fluxus movement and some of the community-engaged work that predates cable access television. I’m noting a similar ethos with your desire to bring people from different scenes and generations together and to work across media.

Scott Kiernan: Well, because I’ve been running this gallery space at 19 Essex, and the label, digging through a lot of work by others made across different time periods; I’m just reminded that I’m typically not drawn to things that fall neatly into any category. I’ve never felt like I fit in that way either, so a lot of the projects I’ve done or been involved with mixed approaches, mediums, and genres — E.S.P. TV tapings are indicative of this.

I think there was a freeness, a co-mingling of art and music scenes at certain times in the past. This was changed by things like art school careerism and aggravated by the increasing impossibility of simply existing economically. But this mixing of worlds that happened 30 or 40 years ago in downtown NYC underground cultures, where art was happening in nightclubs as much as in galleries etc., while revered, is often frowned upon by institutions when it happens now. If it can be canonized or contextualized the way our culture wants after the fact, then institutions are fine with it. But when it happens now, they shy away. I’m fortunate to have worked with so many people (a lot via E.S.P. TV) who were groundbreaking — active in a very active time, who don’t shy away from collaborating with people much younger than them and are still adventurous in their interests.

B O D Y: What are you working on now?

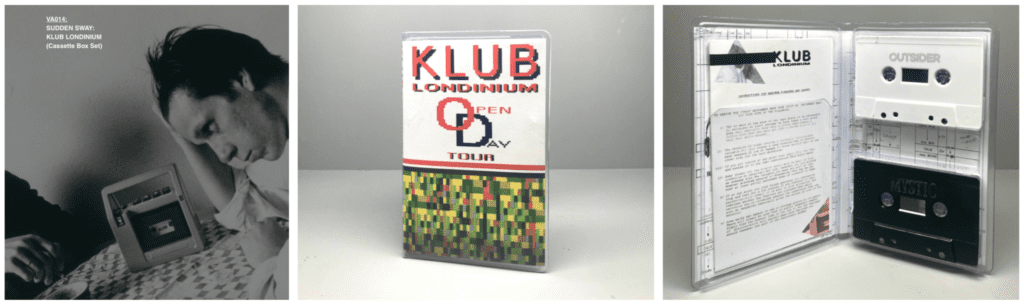

Scott Kiernan: Aside from various video projects; I’ve been focusing heavily on a new gallery/project space in Manhattan I’m running with collaborator Garret Linn. We’ve had about 5 exhibitions in a few months and multiple programs. It’s called Various/Artists, the same name as the record label and publishing project I’ve been doing off and on for several years.

The record label took a break during COVID years, but it’s back now. The latest release is by a group called Sudden Sway – a UK band from the 80s-1990. They’re criminally under-known, which is odd because they did two John Peel sessions (albeit they were elaborate radio plays) and put out records on Rough Trade and even Warner Bros. — but they were more a conceptual pop group than a straightforward band. One project they did in 1990 called Klub Londinium is the latest release on my label and it was in the last show at the gallery.

Klub Londinium was basically a one-day promo event for Sudden Sway’s last record on Rough Trade. It materialized as four different audio/walking tours through London. They had people do a personality test – it was like a multiple-choice questionnaire where you were put into one of four focus groups. You were determined to be either a Hedonist, a Mystic, a Materialist, or an Outsider. Whichever personality you got you were given a walk with the opposite personality. These walks were kind of psycho-geographical audio walks around London. You’d meet an agent at one of four locations who would give you the appropriate tape and send you on your way. A sort of superego voice told you where to go and imparted the history of the route you were on. This would be accompanied by the internal monologue of the character you were “riding with”, inside the mind of …

So, if you were a “Materialist”, you heard the materialist talking to himself the entire time about his wife, the kids, the people at the office, his job, whatever. There was music and sound effects etc. It’s remarkably well plotted out and timed so that you arrive in the correct location for the audio score. It was like live theater, or an early kind of gaming experience. The audio is quite in-depth and really involved, dense, and clever. The group described the tapes to me as follows: A dialogue between space, place and an internal and external voice. All accessible in a real-time interaction with external locations, guided by voice(s) of other minds, usually closed to us.

So, I’ve been quite excited about that project, and it’s in the latest show at 19 Essex which is called Just Step Sideways, (after The Fall song). It’s a psychogeography based show about being in someone else’s shoes and kind of taking the wrong turn. There’s other work in the show by Francisca Benitez, Martin Beck and Bradley Eros. Eros’ work was made during the 80s around spaces in the Lower East Side – most of which don’t exist anymore. They’re like body/memory maps — communing with any threads remaining from a past fervor of activity.

— Jessica Mensch

Further Reading

Artist’s Website

Archive at the Film-Makers’ Cooperative

Various/Artists

E.S.P. TV