Chinese Snow

She didn’t understand what had gotten into her, but all of a sudden Nóra found herself standing on her sixth-floor balcony, folding paper airplanes, instead of attending to her job. She needed to look over a translation that she promised to complete by the afternoon. On the windowsill lay the manuscript, a rectangular-shaped embodiment of her guilty conscience. The languishing strength of the early winter sun sent a shudder down Nóra’s spine. Her attempt at making an airplane resulted in a hat. When she was a child, she knew how to make three different kinds. Did I forget how to do it?—she flattened the paper, struggling a bit longer, hoping that after more than forty years her muscle memory still stored the ingrained movement sequence. Persistence would surely help her remember.

Nóra was translating a young American author’s short story titled “Chinese Snow” into Hungarian. The piece told the tale of an old bird whisperer who shared his tight quarters with a hundred and eighteen white pigeons, and was constantly bickering over the bird droppings with his disapproving neighbors. There was no mention of snow or anything Chinese in the story. Nóra suspected that the title might have been a rare symbolic expression, but she found no corresponding idiom in her dictionaries. Perhaps it was a clever artifice by the author, made up from something similar in meaning?—she took everything into account from Chinese takeout to Chinese puzzles, but got nowhere. What would Chinese snow be like? Yellow. Tiny. Numerous.

She sent the prototype on its way. Instead of sailing down, the slightly misshapen paper creation flew up, though there was no wind; it drifted along the side of the building, higher and higher, seemingly aiming to land on the flat rooftop, but then it suddenly slowed down, and plummeted onto the tiles of the balcony upside down, as though it were a dead bird. Nóra picked it up and threw it again, applying more force. The airplane took an upward path for the second time as well, drawing an even larger circle, only to land on the balcony again. Boomerang.

What is going on? Why won’t it leave this spot? Nóra kept trying until finally, on the fifth try, it spiraled down to the street, hitting the wall with its nose a few times along the way. Before it landed, it got snagged on a leafless tree branch, then it slammed into the cab of a truck. Nóra could have sworn she heard a quiet but firm tap from the sixth floor. An aviation accident… That’s when she saw, from the corner of her eye, Andor’s opalesque Opel. Nóra instantly remembered that it was because of Andor that she went out to the balcony; she’d been waiting for him for hours already. Their relationship was into its second year.

Andor was supposed to arrive around nine in the morning. It was almost noon. He was a married man, but Nóra hoped that in due time he’d leave his wife, just like Nóra’s husband left her for a younger woman. The slight error in this calculation was that Andor’s wife was younger than Nóra. None of her girlfriends believed that Andor would ever ditch his wife and move out. When Nóra was able to look at her situation objectively, she didn’t believe it either. However, she considered any kind of love after forty a blessing. It really irked her, though, that Andor was not punctual. In the meantime she made three more airplanes, all of which ended up on the street. A plump saleswoman from the mini-mart noticed one of them, the one that finished its flight path on the sidewalk right in front of the store. Nóra waited for her to look up to see her reaction. But the saleswoman never did.

Andor had his own key to her apartment, yet he always rang the doorbell. Nóra could immediately tell that something was wrong, but she didn’t ask anything, and headed back to the balcony instead. He’ll say what it is, if he wants to, she thought. Having become more familiar with crimping the folds, she was now mass-producing the paper planes. By the time Andor came outside and stood next to her, another four had glided down and five more waited their turn on the ledge of the chest-high brick wall. He stared at her for a while, his horn-rimmed glasses resting a little crooked on the bridge of his nose, his thick hair more disheveled than usual—his students nicknamed him Rumcajs behind his back, after the gallant robber from an old Czechoslovakian cartoon series, who was known for his tousled hair. He is so small, Nóra thought to herself. We fit together nicely. Nóra was only a hundred and fifty-two centimeters tall, always the shortest in her class. Her fragile fingers mechanically launched the gliders off the balcony.

What are you doing? asked Andor. Nóra ignored the question. Anybody who’s not blind can see what I’m doing, she thought. Give me one! he asked. Make your own! Nóra snapped back. For a while only the rustling of the paper could be heard and, of course, the street noise, but Nóra no longer noticed it. Andor made different models, streamlined fighter jets that flew faster and took sharper turns. At last he spoke: It’s pretty cool that you’re playing with paper airplanes…how did you come up with this idea? Nóra shrugged. I come up with lots of ideas.

Their neatly folded planes took off in pairs, moved away from each other, circled back to reunite, then went their separate ways again for the rest of their seconds-long journey before landing hard on the ground. Nóra could hardly hold herself back from nudging him: Spit it out! Those that already touched down had become mere specks on the asphalt below.

She found out, said Andor quietly. Nóra thought if he didn’t continue, she’d start screaming at the top of her lungs. He didn’t continue, yet she was able to control herself: And? You can imagine… Andor avoided her gaze. After seconds that felt like hours, he added: an insane fight, threats, broken plates…all of it in front of the children. Nóra had a feeling she knew what was coming, her inner alarm was going off, flashing its red light. She felt weak at the knees, but her hands never stopped moving. This is now an entire air-fleet, mumbled Andor. He also tried to keep himself busy by folding more fighter jets, using up the pages of the Hungarian translation of the American short story, “Chinese Snow.” There was only one copy. Nóra, as if she were the last of the Mohicans, never switched to a computer, and insisted on typing on her old Remington. The first and second pages of the short story flew away from between the man’s stubby fingers, floated in the air for quite a while, then crashed. The same fate awaited the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth pages—the first half of the short story.

Soon afterwards Andor let out a long sigh and embraced Nóra. His five o’clock shadow pricked her face. Teardrops rolled down his cheeks. He turned around and made a beeline for the door. It quietly clicked as he closed it behind him. Nóra didn’t need to glimpse at the table to know that he left the key there. She stared off into space. The opalesque Opel sped off from the row of parked cars. Nóra threw the hastily crumbled airplane—page seven—in the direction of the car. She imagined what it must be like to land on the hard asphalt after a corkscrew-patterned descent. She shrugged, tore the remaining five pages into small pieces with meticulous care, and threw them off the balcony.

The bits of paper drifted silently over the street, trembling mysteriously, forming ever-changing, inextricable shapes. Nóra imagined that they were tiny living creatures. Chinese snow… She was cold. She went inside, locked the balcony door, and pulled the thick linen curtains shut. Consequently, she couldn’t have seen that outside, as if on cue, it began to snow. Hungarian snow. Large snowflakes, falling softly on the city, as though they never wanted to stop.

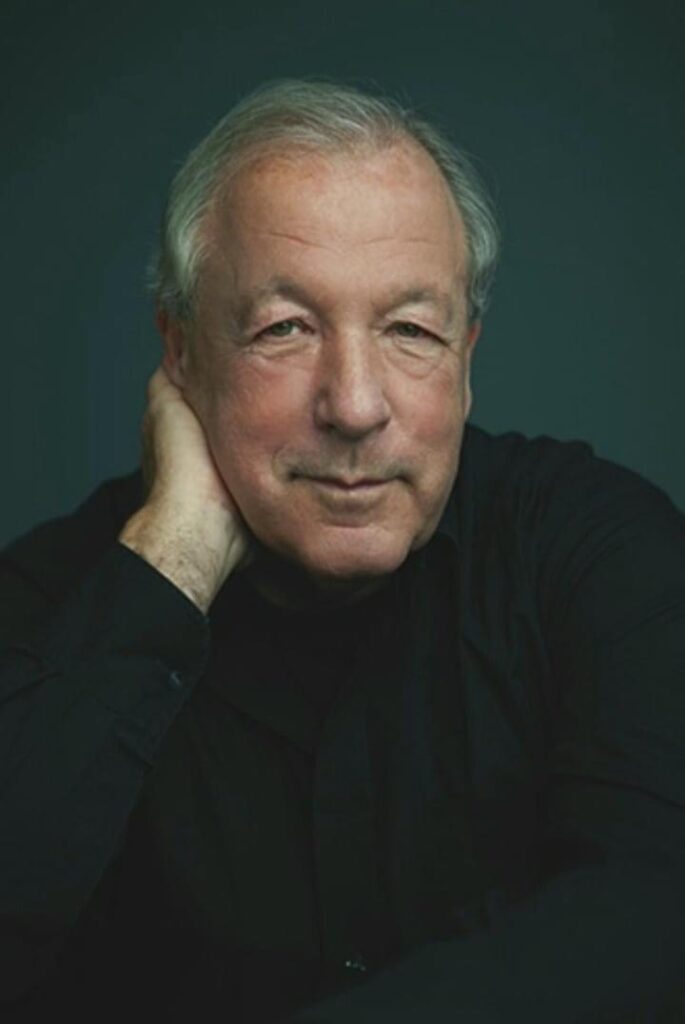

MIKLÓS VÁMOS is a Hungarian writer who has had over forty books published, many of them in multiple languages. He is a recipient of numerous literary awards, including the 2016 Prima Primissima Award, one of the most prestigious awards in Hungary. His most successful book is The Book of Fathers, which has been translated into nearly thirty languages. His ancestors on his father’s side were Jews who perished in the Holocaust. Fortunately, his father—a member of a penitentiary march battalion—survived. Out of the five thousand Hungarian Jews sent off to their deaths late in World War II, only seven came back. His father was one of them. Vámos was raised in Socialist Hungary unaware he was a Jew. In an effort to save himself from his chaotic heritage, he turned to writing novels.

About the translator:

ÁGI BORI originally hails from Hungary, and she has lived in the United States for more than thirty years. A decade ago, she decided to try her hand at translating and discovered she loved it. She is a fierce advocate for bringing more translated books to American readers. In addition to reading and writing in Hungarian and English, her favorite avocation is reading Russian short stories in their native language. Her translations are available or forthcoming in Apofenie, Asymptote, B O D Y, the Forward, Hopscotch Translation, Hungarian Literature Online, the Los Angeles Review, Litro Magazine, MAYDAY, Northwest Review, and Trafika Europe. She is a translation editor at the Los Angeles Review.