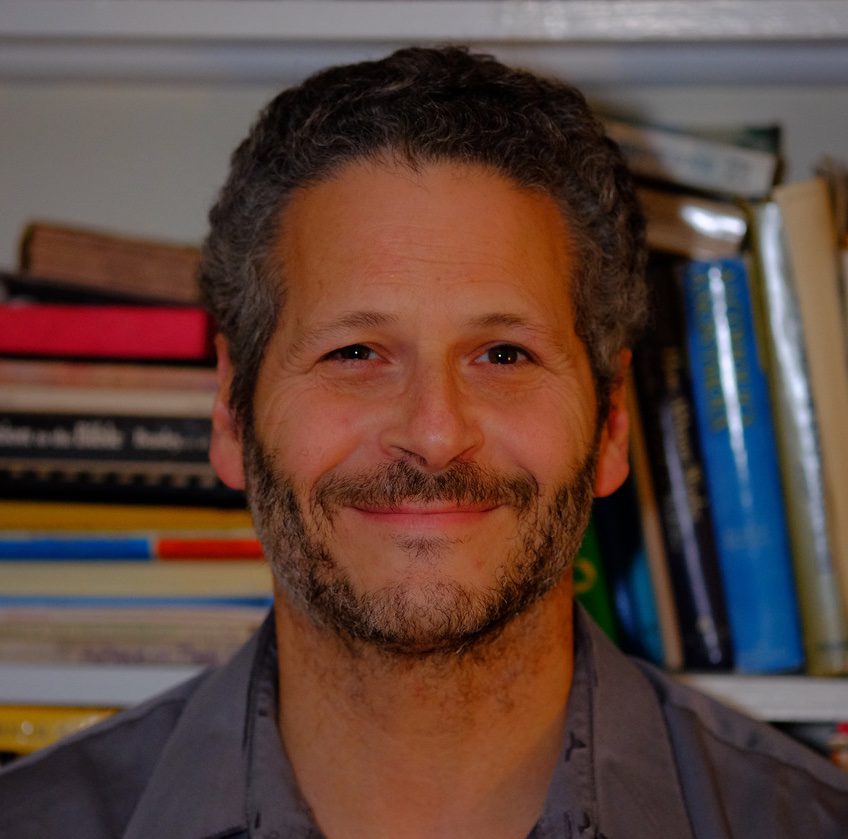

The American poet Paul Hostovsky has a remarkable family history. His father, Egon Hostovsky, a relative of Stefan Zweig, was an acclaimed Czechoslovak writer and journalist who fled from the Nazis in 1939, passing through Belgium, France and Portugal before ending up in the United States — “always one step ahead. He was lucky,” noted Paul in one of his poems. Overseas, Egon married for a third time. He died in 1973 when Paul was fourteen.

Paul reminisces about his father in a number of his older and more recent poems. When he was a boy, though, his focus was less on his father’s literary talents and more on his difficulties with English. He wrote about what it was like to have a father with a foreign accent and the unusual name Egon (“pronounced Egg-on”) who never lost his love for his homeland and made sure his son knew how to spell the long name of that distant land, Czechoslovakia — unlike everyone else in his class. In return, Paul, a native-born American, patiently taught him sports terminology so his dad would no longer be under the illusion that “a home run was something you did when your mother / forgot to pick you up after a baseball game.”

It is characteristic that Paul Hostovsky became so fixated on his father’s flawed English. In his poetry, he is extremely sensitive to spoken language. This may be precisely because of the conversations with his father — a non-native speaker — in his childhood, which taught him that mutual understanding is not something to be taken for granted. Consequently, his poems are often based on curious or comical exchanges he has participated in or overheard. In interviews, poets are regularly asked what the trigger for writing a poem was, whether it was an emotion, an image, a sound, or perhaps a sudden compulsive need to tell a story. It seems that, for Hostovsky, the impulse is just a word or phrase he has remembered, which he manages to use as an example that describes the entire character of the person he is writing about.

So, for instance, in his new collection, Pitching for the Apostates (2023), he sums up his wife’s ex-husband with the adjective “interesting” in a poem titled the same, which begins:

“Interesting,” says my wife’s ex-husband

to himself (“He can fix anything,”

she likes to say. “Except for his broken

marriage,” I like to say.) as he considers

the door jamb, the strike plate, the lock bolt

on the door he’s installing in our kitchen

because, interestingly, we all get along now

and I actually like the guy, so I hired him

to do some carpentry. Because I can barely

open a door, much less install one.

In the rest of the poem, the poet reflects on the differences between himself and this extremely practical guy until he realizes in amazement how lucky he is that his wife left the handyman “for a man who prefers to sit and write about life // than live it”. However, he would probably never have written the poem if the word “Interesting” hadn’t got stuck in his head—the word his wife’s ex-husband is so fond of using when he is installing or fixing something.

Hostovsky’s own favourite word is “bicycles”, to which he has written an ode of the same name (first published in B O D Y), which is the opening poem in the new book. He had already lauded the word in his earlier collections and for some reason has evidently fallen in love with it to such an extent that he has no intention of relinquishing it, apparently even on his deathbed:

[…] In fact

I want bicycles to be my last word, my dying word —

not I love you, or bless you, or God forgive me,

but bicycles. And the people standing over me —

if there are any people standing over me at the last —

will look at each other and ask if they heard me right —

“Did he say bicycles?” “Yes, it sounded like bicycles”

Hostovsky’s fondness for words and keen ear for spoken language benefit his writing: he can record and create dialogue in a brilliant and natural way. In this respect, he has more in common with short-story writers than with most contemporary poets, who tend to avoid direct speech. At the same time, through his artful phrasing—the careful arrangement of the lines and skillful use of line breaks — he utilizes the stylistic advantages of poetry. In particular, he delights in embedded clauses, important building blocks for the humour in his texts. Take, for example, the phrase “if there are any people standing over me at the last” in the quoted extract, for which a whole line is set aside. It functions similarly to an in-between move in chess; it represents an unexpected sidestep, drawing the reader onto the next line even more while simultaneously helping to produce the humorously melancholy tone of the poem.

Pitching for the Apostates follows on from Hostovsky’s previous books and delivers another batch of memories from childhood and youth (it is as if middle age doesn’t deserve much attention), which are never boring, and some of which might even make the reader laugh. But old age has also crept into the collection: for example, when the poet realizes that he is beginning to be known as someone who suspiciously often starts a sentence with the words “forty years ago”.

And the twenty- and thirty-somethings

and forty-somethings are doing the math:

He must be a pretty old fucker, they’re thinking,

if he can say “forty years ago” in a sentence—lots

of sentences, too many sentences—and get away with it.

You might guess from the quotes above that Paul Hostovky is a poet who, at least outwardly, doesn’t take himself too seriously. He is also no stranger to self-irony, now such an underrated part of the toolkit of a good writer. But that doesn’t mean that he is indifferent to the world around him or is incapable of taking things seriously. In the poem “Flags”, he describes buying postage stamps. When he is offered three types at the post office: (American) flags, birds, and flowers, he rejects the flags, because these days the only Americans “driving around with an American flag // flapping loudly in the wind / are the ones insisting they’re the only / Americans.” And so:

I went with the birds. And also the flowers—

I bought two books of stamps because

I write a lot of letters. And even though

some birds and some flowers

are just as territorial as some Americans,

at least the birds and the flowers know

they’re not the only birds, the only flowers.

Hostovsky ends Pitching for the Apostates with a poem titled “His Last Poem”. We can only hope this doesn’t mean the author is ready to hang up his poet’s hat. Perhaps he is already working on another collection in which he will present new, fresh, funny, and sometimes touching poems full of lively dialogue. And as a representative of the “thirty-somethings”, I’d say it wouldn’t even matter if most of them were set forty years ago.

— Jan Zikmund

JAN ZIKMUND is a B O D Y editor. He works for the Czech Literary Centre in Prague.