Anna Hawkins is an artist who works primarily in moving image and installation with an interest in the ways that images, gestures, and language are circulated and transformed online and the impacts of technology on the intimate spheres of daily life. Her works have been recently exhibited and screened at transmediale (Berlin, DE), CCCB (Center of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona (Barcelona, ES), the Istanbul International Experimental Film Festival (Istanbul, TR), Dazibao (Montréal, CA), Images Festival (Toronto, CA), and The Art Gallery of Alberta (Edmonton, CA). In 2022, she was longlisted for the Sobey Art Award, Canada’s preeminent award for Contemporary Art. She is currently an Assistant Professor in Studio Arts at MacEwan University on Treaty 6 Territory ᐊᒥᐢᑿᒌᐚᐢᑲᐦᐃᑲᐣ (Amiskwacîwâskahikan), Edmonton, Canada.

B O D Y’s art editor, Jessica Mensch, caught up with Anna recently to talk about her work and the thinking behind her artistic practice. The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

B O D Y: Hi Anna, thank you for meeting with me to discuss your work.

Anna Hawkins: It’s nice timing at the end of a semester of teaching when I’m feeling very ready to get back into my own thoughts and work.

B O D Y: You have an undergraduate degree in Art History. Had you planned on pursuing a career in that field? If so, can you tell me about your transition into making art?

Anna Hawkins: While doing my undergrad, I really thought that Art History was the area I was going to pursue, either through curation or possibly restoration. It wasn’t until the end of my degree that I started to develop a practice. I was working at a non-profit film and media arts center in Pittsburgh called Pittsburgh Filmmakers (I worked there throughout my undergrad) and that’s where I started to have an interest in working with moving images. I borrowed a Super 8 camera for a summer and started to experiment with film a bit. I eventually began trading work hours for courses: cleaning the dark rooms in exchange for an intro video course and later working as a TA for video editing and animation courses.

I think I eventually came to the realization that I was more compelled to develop an artistic practice than I was to do the kind of academic writing and research that would be involved in continuing in Art History.

B O D Y: Has your background in Art History impacted your approach to art making?

Anna Hawkins: I think it definitely has. Certainly, it had a big influence while I was doing my MFA where the body of work I developed was centred around looking at art historical images and genres through the lens of the internet. I was thinking about the way that images circulate and how the internet has profoundly changed the way that we understand and interact with images and artworks.

B O D Y: Yes! In much of your work, the viewer gets to know the subject in a fractured sort of way – through reflections in mirrors and windows, shadows, screen images, and body parts, for example, a pair of legs walking down a hallway or a hand grasping a hairbrush. In your recent work, Blue Light Blue, there is this same fractured style of character development, but with the addition of a soundscape, and camera and lighting style that recall the film genre of horror. What was your thought process behind layering these stylistic approaches in a single work?

Anna Hawkins: I think an interest of mine for a long time in my practice has been the kind of shifting awareness that we experience as viewers of moving images. Moving images are incredibly seductive and are usually intended to immerse the viewer in an experience where they lose themselves (particularly in narrative cinema). I’m really interested in moments when that immersion is broken, and I remember that my body is seated in front of a flat image. I started working with this in my video Fall Fell Felt, where there are moments when my reflection appears on the surface of the screen, breaking the illusion or sense of immersion. I was influenced by Linda Willams’ text “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre and Excess” and her discussion of “body genres” (horror, melodrama, and pornography). These films elicit a bodily response from viewers and (says Williams) most often it is women’s bodies that are used on screen to incite this response. This led to Blue Light Blue and an interest in horror. Horror is a genre where, when we become totally immersed, we have a bodily reaction to what we see on screen – you might scream or wince or jump — and, in that reaction, you are reminded of your own body and the fact that you are merely a spectator. I think that’s why people often laugh after they scream or strongly react in a movie theater. So, coming back to your question: I think horror, for me, felt like the right genre to explore the moments of immersion and loss of identity or sense of self that can happen as a viewer of moving images as well as the awareness that returns when we respond in a bodily way. If that makes sense?

B O D Y: Yes. Thanks!

B O D Y: Your narratives read as psychological inquiries. For example, in Love, you seem to be asking the question – what is love when it becomes disembodied, and its expression or experience is mediated through screens and images? You also state that the onscreen text was inspired by Flusser’s book, Does Writing Have A Future? Can you tell me a bit about your approach to storytelling in your work?

Anna Hawkins: Narrative as an interest is something that has only emerged within my last few projects. It started with Fall Fell Felt, though it was unplanned – a sense of narrative is something that emerged in the process and sort of surprised me. Then in Blue Light Blue I consciously worked with it, developing a rough “script” (more of a detailed shot list) before shooting. In Love, I began the work knowing that language was my interest and specifically how language functions online. In Flusser’s text he responds to the question in the title (Does Writing Have a Future?) with a “no”: saying that the function of writing can be performed by other (increasingly digital) methods. Thinking about this, Love uses images culled from Instagram to create a visual narrative.

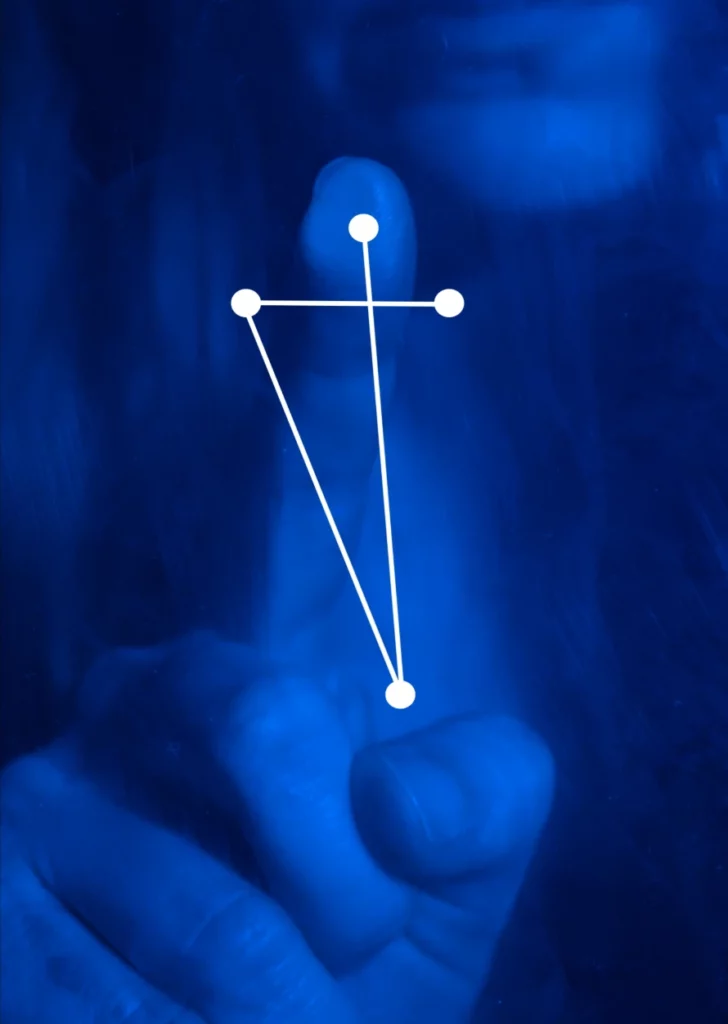

Anna Hawkins: The onscreen text was only developed after all the visuals were complete as an attempt to translate or make sense of the story the images were telling. I’m working on a new project now, Constellations, where I am attempting to write a voiceover simultaneously while shooting the work. I’ve actually found this quite challenging I think because as you say, my works do function or begin as inquiries: working through a question or questions and not quite knowing what sort of narrative will develop. I love the idea of having a script to work from, beginning a project through writing and then developing the visual part of the project, and I’m still working to make that happen, but I’m not sure that’s how my brain works!

B O D Y: Can you explain your process a bit more in making Love?

Anna Hawkins: The work was created for an Instagram residency with Dazibao in Montreal. So, over two months, I created 30 separate posts that were released approximately every other day. So, the work was shot and edited in a totally chronological way. Each post centered around a type of image that I found while searching the hashtag #love – which is the most used hashtag in the history of the platform and has over two billion associated posts.

I was thinking about the way that language exists online: when you search a word or hashtag you don’t get a definition of that word, you get all the information or images (in the case of Instagram) that have been associated with that word. So, each post that I created gathered together a specific cluster of imagery found searching #love. Clusters were identified with a single additional theme/word—like fruit, pets, eyelashes, or tattoos. Using my own footage to respond to and link each post together is how the project unfolded. At the end of the residency, I had around seven minutes of work without sound that I knew I wanted to add my own text on top of to explore a totally different use of language.

What I ended up developing was a sort of love letter written to the viewer by the Instagram platform (or maybe even more generally the internet) considering what kind of an understanding of “Love” might emerge from the images I had collected/created.

B O D Y: Watching it, I had the uncanny sense that I was losing my/a body. By the end, I felt there was no body to speak of – in terms of there being a desiring entity and an object of desire!

Anna Hawkins: Yes! I’m so glad to hear that was your experience. I suppose it’s sort of an attempt to explore the abstraction of language. A word like love is so very tied to, as you say desire and the body, but when you remove those elements, what remains?

B O D Y: A common discussion point regarding the ethics of AI is the fact that AI has no body, and therefore operates outside of an ethical standpoint.

Anna Hawkins: That’s really interesting, thinking about what ethics (or language) mean to an entity without a physical body/form.

B O D Y: Yes, it seems so obvious, but in the context of AI, provocative to consider.

In your recent solo show at the Art Gallery of Alberta, you included a small painting. It was positioned at the beginning of the installation. Can you tell me about this decision – including an object in your installation?

Anna Hawkins: Yes, this an interest for me and something that I’ve been developing more in Constellations. At the Art Gallery of Alberta, the watercolour included was based on a political cartoon that appears in the installed video, Blue Light Blue. The cartoon is from the French Revolution and depicts anthropomorphized lampposts chasing after revolutionaries. It was an important discovery for me in the research of the project because it encapsulated the way that artificial light has long been associated with surveillance and control. Blue Light Blue examines these ideas with blue light and digital devices. The watercolour combined imagery from the original cartoon and from my film. I think this brings me back to one of your initial questions about image versus reality and allows me to explore images as physical objects in a way that moving images never quite can. I’ve said for a long time that many of the ways that I work with video — using a lot of compositing techniques — is an attempt to have a more physical connection with a totally immaterial medium. I think the immateriality of moving images can be frustrating at times so I’m enjoying experimenting with actual tangible materials!

B O D Y: Is that what motivated you to include film footage in Blue Light Blue? In comparison to video footage, film footage has a visual texture which gives it more of a material presence.

Anna Hawkins: Yes, I think partially. It does visually have more materiality, I think; however, I still edit and finish everything digitally so my physical connection to the material of film is limited to the shooting process. Conceptually, for Blue Light Blue, using film was important because I saw it as an experiment: film is developed for exposure with either daylight or tungsten light. So how will it respond to this new type of blue light that has emerged since it was created? It also became part of the narrative structure of the work. Film is used to express the viewpoint of the human protagonist and video is used for the digital one (roughly speaking).

I was also drawn to work with film again (it had been over 10 years) for the way it necessitates a release of control. For several years I worked pretty much exclusively with found footage because of this. You work with what you find and embrace the differing qualities, the weird framing or whatever. Film is a bit like this since there’s a time delay between shooting your footage and seeing the results. You don’t know exactly what you will get, and you have to embrace the results. Working with video is very different for me and I can really obsess on shooting and getting everything “right.”

B O D Y: Can you tell me more about your current project?

Anna Hawkins: My current project is titled Constellations. And I’ve already been working on it for some time. It started based on a location very close to my home in Edmonton: Coronation Park. The park is home to a not currently functional planetarium named after Queen Elizabeth II in honour of her coronation and was opened in 1960. The planetarium has these wonderful, somewhat crumbling, mosaics of the astrological signs on the pavement out front. The park also is home to the newer Telus Science Center which has its own planetarium. I was interested in thinking through these three very different ideologies present here (astrology, imperialism, and an institution named for a giant telecoms corporation) and the way that they conceptualize the cosmos.

B O D Y: Do you feel compelled to make sense of this shared theme of the cosmos, or will Constellations be more of a rumination on this?

Anna Hawkins: It’s definitely more of a rumination or a starting point and the work has expanded quite a lot since I started it. I shot additional footage while on residency in France last summer and will do a bit more shooting while in Switzerland this summer. The project is quite interested in the idea of projection, both technically with the history of projection and moving images (and planetariums) and also the psychological process of projection and the way that astrology is a means to project ourselves and images onto the stars. I’m drawing a connection to the internet, a similarly vast space into which we cast our own identities, and thinking about algorithms and their correlation to constellations: the way that discreet points or clicks or stars are connected to create a larger image that can be used to interpret identity and also predict actions or events.

B O D Y: I’m really looking forward to seeing this work!

— Jessica Mensch