Photo: Dominik Bindl

Johanna Strobel is an interdisciplinary artist, working across installation, sculpture, painting, video and VR. She holds degrees in Information Science and Mathematics from Regensburg University and graduated in Painting and Graphics from the Academy of Fine Arts Munich. In 2020 she received an MFA from Hunter College.

Strobel’s work is concerned with time and related concepts like change, entropy, and information. Weaving together disparate references spanning across histories and geographies, she explores the entanglement between philosophy, semiotics, and actuality.

Strobel’s work has been exhibited in Germany, Italy, Taiwan, Korea, Canada, and the US, including New Museum Nuremberg, Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn, Museum Gunzenhauser, Chemnitz, Kunstverein Munich, Institute for Modern Art Nuremberg, Bethanien, Berlin, Nappe Arsenale, Venice, Nada House, New York, and NARS Foundation, Brooklyn.

Strobel has received grants from the German Academic Exchange Service, the State of Bavaria, the German Artist Alliance, and the German Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media.

She is a member of NEW INC, the New Museum’s cultural incubator, and Mensa International.

B O D Y Art Editor Jessica Mensch caught up with Strobel in New York this fall to talk to her about her work and practice. Their conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

B O D Y: Where did you shoot the video for your installation, Bonne Chance?

Johanna Strobel: At the Bonneville Salt Flats. The salt flats are dried-up remains of a primeval salt lake in Utah, close to the Nevada border. It’s a remote area except for a small town right on the Nevada side of the border. The town basically consists of three casino hotels, a dispensary, and a trailer park.

B O D Y: When were you there?

Johanna Strobel: Last September or October.

B O D Y: Did you go specifically to see the flats?

Johanna Strobel: No. I went to see Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels, a land art piece that is a giant clock, calendar and compass. It consists of four concrete tunnels arranged in a cross formation. They are positioned so that every solstice the sun shines straight through the tunnels. It’s like Star Gate meets a canal pipe – very strange and beautiful. The Sun Tunnels are located in a remote valley of the Great Basin Desert. There is no phone reception, just unmarked dirt roads.

When going from the airport in Salt Lake City to our hotel we passed through the salt flats. I had never seen a landscape like this. Separated by fences and trenches, the highway cuts through this endless white plane that’s sometimes covered with water and reflects the sky. Close to the Nevada border and the city is a scenic viewpoint with a parking lot. People just drive over the edge of the parking lot onto the Salt Flats. Some make campfires, some just speed and do donuts. For almost a hundred years the flats have been used as a land speed record test ground.

Driving on the salt feels very strange because there are no reference points in this monochromatic landscape; the experience of space and distance is surreal. I thought it would take about twenty minutes to cross, but after driving for twenty minutes it was as if the car hadn’t moved.

Apparently, they still find the wheels of carriages from when colonial setters moved west — a lot of them died crossing the flats after getting stuck in the salt mud, or from thirst after underestimating the distance.

B O D Y: Can you tell me a bit about the narration in the video?

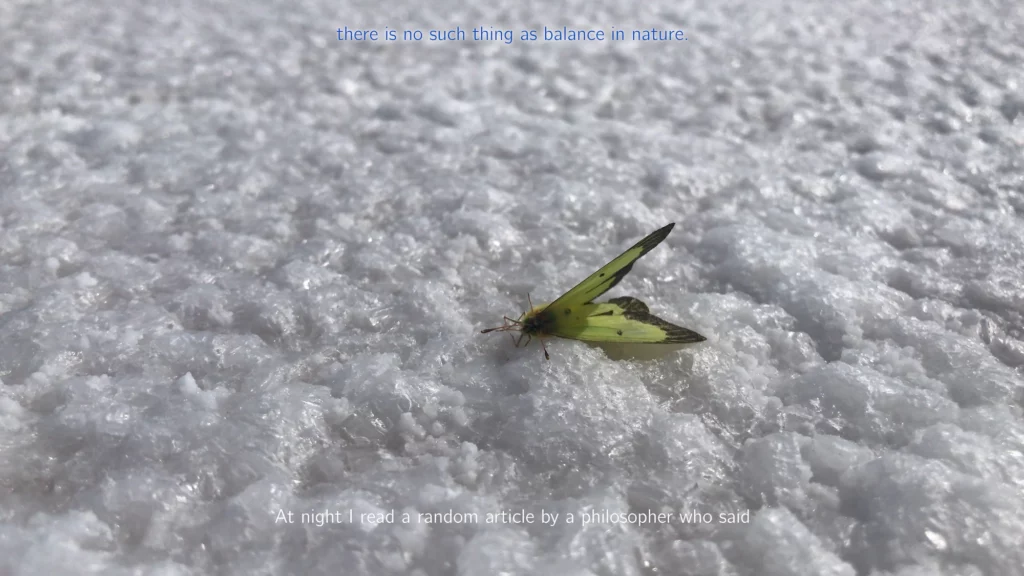

Johanna Strobel: The work was shown in a group exhibition titled “Momentum” at New Museum Nuremberg. The curatorial team invited twelve artists to create works responding to the concept of momentum, i.e. — the swift passing of time, and the energy generated by a specific situation. This invitation came a couple of weeks after I had shot the footage — which was a perfect coincidence. The archaic landscape of the Salt Flats was created by a natural disaster thousands of years ago. It has remained mostly unchanged until very recently. Mining and speeding on the flats, and the human-made climate crises are endangering and destroying this seemingly dead and immutable place.

The narration is very layered and has many literal, linguistic, philosophical, poetic, and personal references. Going back and forth between these two spheres of knowledge and my own personal memories and observations is something I do a lot in my work. The images in the video — the Salt Flats, my disappearing shadow, and the dead butterfly – for me recall change, loss, eternity, time, and motion, as well as the changing of one’s own position and viewpoint in time and space.

B O D Y: I noticed in your writing as well as in your narration for Bonne Chance, you engage in wordplay or a circular kind of logic. Can you tell me about this? Your first language is German, is this approach specific to English being your second language?

Johanna Strobel: A second language is a gift. I can’t express myself as clearly in English as I can in my native language, so I’m always looking up words in the dictionary and thesaurus while working on a text. I search for specific connotations and compare near-synonyms. A single word can have multiple meanings in one language and be translated into several words in the other. “Change”, for instance, has multiple translations with different meanings in German. Because I mostly write and read in English, I spend a lot of time thinking about words and constructions. For example, it’s interesting how the language around time is constructed. Most of it uses spatial language.

B O D Y: Can you give me an example?

Johanna Strobel: On, in, over time — a lot of prepositions are used to describe both space and time. This is probably the case in many languages, but I notice it in English because I need to decide and think about each word I use. This also inspired me to think more deeply about my native language. For example, “momentum” in physics translates to “das Moment”. The English, “moment”, has several German translations, one of them being “Augenblick”, which means, “blink of an eye”. For Kierkegaard, “Augenblick” is an abstract moment in which the now and eternity become one. Thinking of the actual time between two blinks of an eye, led me to research how often a person blinks. On average, it’s every four to six seconds. So, you could say that the metaphorical “Augenblick”, (the moment), literally takes four to six seconds. Psychological experiments have shown that we perceive the duration of the present as being three seconds long. So, I could argue (winkingly) that the “Augenblick” encompasses a fraction of the past, embraces the present, and contains a blink of the future — the now and eternity…So, I full circle back to Kierkegaard.

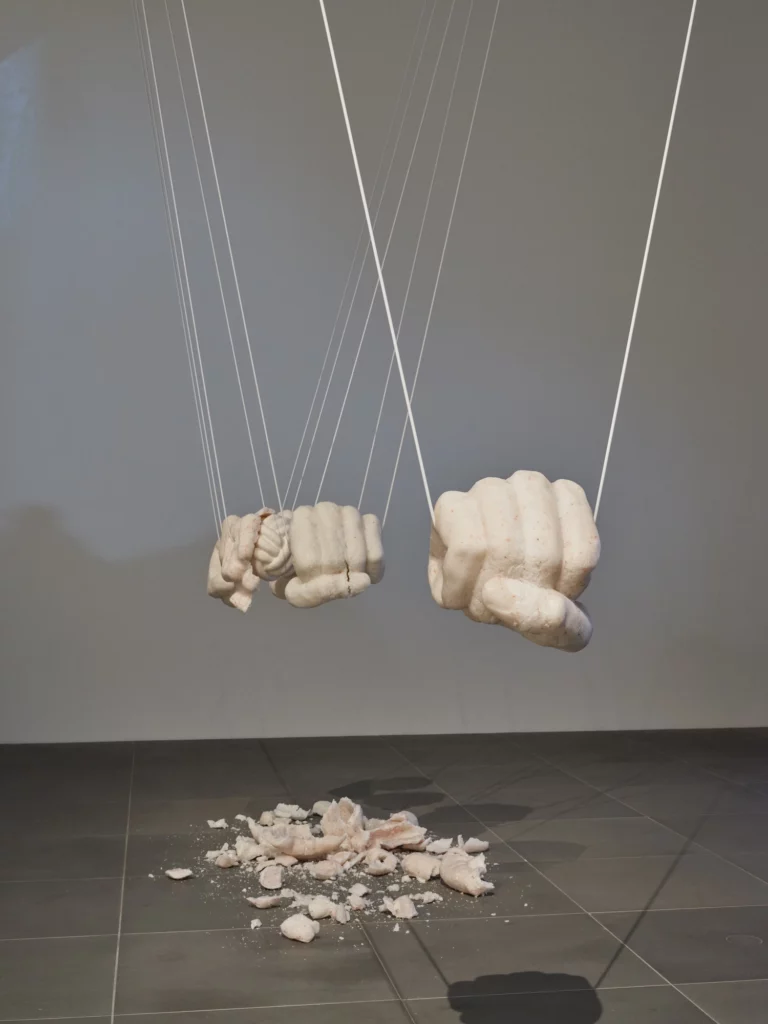

B O D Y: Can you tell me about the large fists suspended in the center of the gallery space? I understand there’s a ceramic knot hidden inside each hand…

Johanna Strobel: I wanted the video work to have a physical, handmade counterpart that would talk about change, time, loss, the now, and eternity in a different way, and add to the thoughts the video evokes without illustrating or repeating them. I also wanted to work with salt, and I wanted the sculpture to change irreversibly over time. Starting from there, I searched for a form and shape. I chose the symbol of the fist because it speaks to change, to a revolutionary force, to transformation, while the knot inside represents the unsolvable, infinite, and eternal.

Five of the six fists suspended in the gallery formed Newton’s Pendulum which visualizes the conservation of momentum. The fists were double-sided. The sculpture was activated weekly. With every swing the fists broke open, revealing the ceramic knots. The salt crust that fell to the floor remained as a relic of a change. The sixth fist was hung outside the pendulum system and remained unchanged while it formally indicated the movement of the pendulum.

B O D Y: How did you keep the knots from crumbling?

Johanna Strobel: They were made from pretty thick ceramics and the impact wasn’t great enough to break them, while the salt of the fists was very fragile and broke apart easily. Even if the knots had broken, it would have just been part of the work.

B O D Y: So, when you think about the fists hitting each other, and transferring that momentum or energy from one fist to the next, and having the fists destroyed in this process, disrupting that closed system…how does this relate to your thoughts on momentum, speed, motion, eternity, and change?

Johanna Strobel: I was thinking about how some changes are irreversible and lead to something else that cannot be repeated. With every swing of the fist, the whole system changed making each following swing and transfer of momentum unique. In the beginning, the fists formed a straight line, but with every activation, parts broke off and the pendulum got more out of balance. By the end, the fragmented fists couldn’t even hit each other.

B O D Y: Was the weekly activation open to the public?

Johanna Strobel: I didn’t want it to be a spectacle about the artist destroying the artwork, so the performances took place without visitors. For me that was a big part of the work – visitors could see the shards and pieces of the fists on the floor as proof of the change that had occurred, but the action that had triggered the change was invisible.

B O D Y: In a way, the situation you created mimics the shrinking of the salt flats in Utah – as a viewer you are met with the quiet stillness of the evidence of change, but no direct experience of the change itself…You’re giving the viewer two very different experiences of time at once. Maybe this is why it’s so difficult for some people to accept climate change — they can’t make sense of these two experiences of time.

Can you tell me about the work I’m seeing in your studio?

Johanna Strobel: There are multiple parts to this sculpture. There’s a heating element at the top. Over time the wax bird under the heater melts, filling this part in the lower half of the sculpture. This lower part is actually a mold for an egg shape. A sister sculpture reverses this process, melting the egg back into a bird. The sculptures act out a cycle, but the cycle ultimately breaks down as the wax evaporates. Eventually, just fragments are cast and remelted until the cycle stops.

Like in my salt work, I was thinking about the meaning of the materials. I chose these materials, ceramic, wax, and silicone because of their transformative and indexical qualities. Heat transforms ceramic from a soft, unstable, malleable state into a stable, enduring material. Silicone is, once liquids are mixed and cured, both flexible and particularly resistant. The liquid and solid states of paraffin lie close together — wax melts at body temperature. So, it’s a transformative sculpture made from transformative materials.

B O D Y: Why did you decide on using an electrical heating unit to melt the wax when you could have used a candle?

Johanna Strobel: Because that ceramic heating lamp is actually used for breeding birds.

B O D Y: OK, wow. The fact that the material will ultimately exhaust itself, and disappear over time — does that have a similar appeal to you as the pendulum fists?

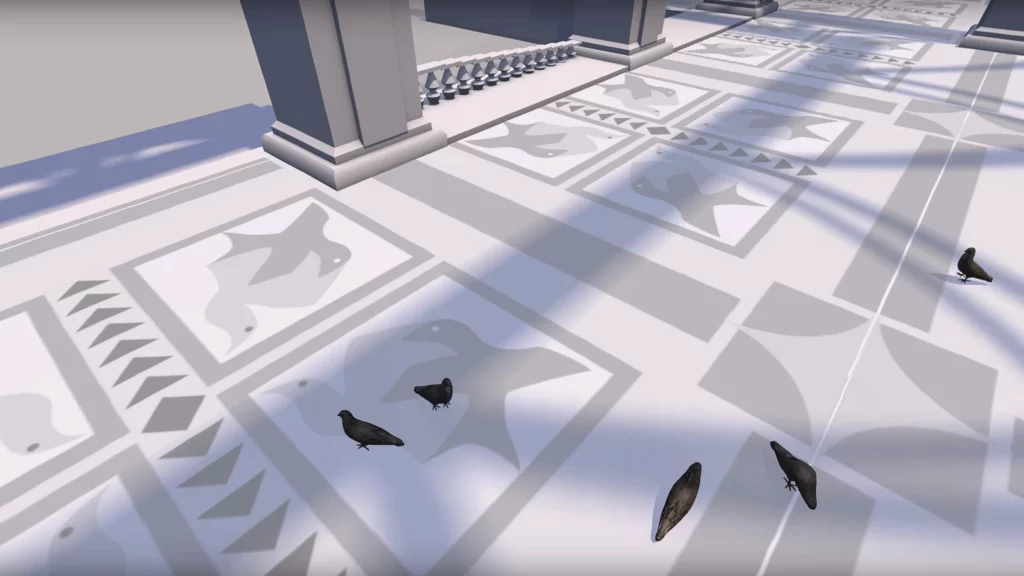

Johanna Strobel: I want to make another sculpture that can be turned around so that it functions like an hourglass, so it becomes a kind of clock. But yes, both sculptures speak to change as loss and disappearance, in this case of a species of bird. The sculptures are physical companions to a VR piece, My Heart is Not a Clock (Martha), about the extinct Passenger Pigeon that I made over the pandemic.

B O D Y: Tell me about this.

Johanna Strobel: With all cultural institutions and most public spaces closed, I was thinking about how I could make an artwork that people could genuinely experience in their homes that was not a reproduction of an artwork.

The work is a 360-degree video. It comes with a dedicated website. I received a very generous grant which allowed me to design cardboard VR Headsets and distribute them for free. Viewers could go to the website and mail order a free headset to experience the work in their homes.

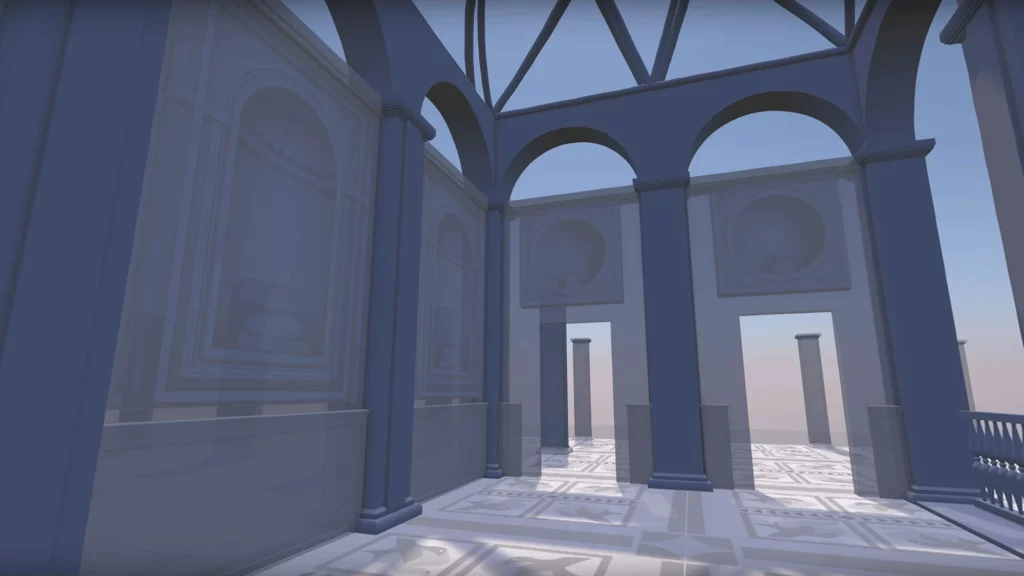

This piece itself explores philosophical concepts of circular time and the loss of a species due to human-induced extinction. The voiceover retraces the Passenger Pigeon’s extinction in the early 20th century and its possible future de-extinction through cloning. The architecture in the piece is based on the Villa Farnesina in Rome, which I visited over ten years ago. It stuck with me all this time because the loggia is covered in monochromatic frescoes of empty pedestals.

B O D Y: Do you know why?

Johanna Strobel: I guess it is a visualization of the absent.

I chose this motif after finding a theory on Reddit that explained there were four directions of time. Normally we think of the past and future as counterpoints, with the present positioned in between. According to this theory, there is a counterpoint to the present — the absent, which lies between the future and the past… the directions of time imagined as if on a compass.

The Passenger Pigeon went extinct in the early 20th century. The story is unbelievable. The birds migrated in flocks of billions. It took days for a flock to pass by, but they went extinct within twenty years. When the population started to decline and the flocks became smaller, the birds’ numbers rapidly diminished – they didn’t have any defense mechanisms, because in a big flock, they never needed any. The last known Passenger Pigeon, Martha, died in a zoo in Cincinnati. After her death, her remains were frozen and her skin was mounted and displayed at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington. Later her skin travelled back to Cincinnati for the unveiling of a bronze memorial to her species.

Everything about this story is bizarre. Recently, discussions have begun on cloning the pigeons due to the large number of skins and other genetic material available. This just opens another Pandora’s box. What will it do to the environment if you release these cloned birds? And…if we can let one species go extinct, clone it, and simply bring it back, why would we try to save anything?

So, thinking about this cycle of life, and the future circling back — or the return of the past due to cloning of these birds or rather, bringing them back from the absent into the present, connected the story of the passenger pigeon to this theory of time that is both circular and like a compass.

B O D Y: Clocks are repeated motifs in your work. In your publication, Geometric Times, Linguistic Spaces, you mentioned a clock at your childhood kitchen table that antagonized you…

Johanna Strobel: I’ve always been interested in time, in constructs, formulas, and measurements since huge parts of our lives are measured and compartmentalized. Most of these things are made up and arbitrary. There is no cosmic or natural reason for a day to have twenty-four hours or an hour sixty minutes and so on. I’ve always had a hard time with institutionalized time. Especially as a child in school, where every part of the day was scheduled and structured. I was a very good student, but I had trouble working in assigned time intervals and with being on time. I was a quick learner and often bored at school. I finished the exercises before the others and had to wait. It really annoyed me that my schedule was dictated from outside. You never have control over your own time in capitalism. Even as a child, I felt the negative impact of that. Not an early riser, I would often sit groggily at the kitchen table in the morning at breakfast and stare at the clock you mentioned.

It was a red-framed wall clock that pictured an illustrated sunrise/sunset over the ocean. The ambiguity killed me. I thought there must be a way to find out if it was a sunset or sunrise. I wanted the image to change, to make sense with the actual time of day. The transformative moment between day and night that was on pause in this image felt very unsatisfactory to me.

I made the first “failed clock” piece referencing this clock when I had a windowless studio in grad school. This space finally freed me from measured time because I never knew what time it was.

— Jessica Mensch