The Silver Pocket Watch

Rabbi Nachman was sitting on the bench at his table of unpolished pine planks, absorbed in an old book, seeking new meanings for the ancient sacrifice of the Pesach lamb, for the bread baked in the sun from dough that has not had time to leaven—after centuries of bondage, emancipation had arrived too quickly—and for the bitter herb that even in good times must recall the hard times of bondage.

It was a hot spring day. The door and windows of the room were open wide. And there was silence. Deep silence. All of a sudden, happening to lift his eyes from the book, he saw a figure, dark against the bright sunbeams. Screwing up his eyes, he saw that it was a tall thin man with a matted white beard framing a pale face with prominent cheekbones; the man’s forehead was high, bulging, his clear blue eyes were sunken in their sockets; a long bluish weatherworn caftan hung like an altar cloth from his thin body; and he held a long, knotty staff of oak.

The rabbi had not heard the man’s footsteps as he approached. He had heard nothing.

And now the man now stood in the doorway, without saying a word. It was a wanderer, who probably had not dared interrupt him as he read. But on seeing the rabbi looking at him, the stranger spoke in a soft voice:

‘I come from afar and I still have a long way to go, Rabbi Nachman. And on the eve of Pesach, I find myself without any money to buy unleavened bread, meat, wine, bitter herb . . .’

So that was it: he was a beggar caught out late on the road. Late, indeed, thought Rabbi Nachman, since at that hour every other wanderer had taken shelter under a roof or was at home with his family, if he had a home and family, or in a synagogue, waiting to be invited to another’s home to partake in the Seyder, the Pesach evening meal.

But here was a wayfarer, waiting in his doorway. What could he give that wandering beggar, when he didn’t have two pennies to rub together? There was never money in the rabbi’s house overnight, since what he received in the day, he shared among the poor before the evening prayer.

At a loss, Rabbi Nachman began rummaging in the drawer of his table, in his cupboard, under his bench, in the hope of finding a stray penny to give the wanderer as alms. But, of course, he didn’t find a single penny. Only in the houses of the wealthy do you find pennies forgotten in drawers or which have rolled into corners. The rabbi fretted as to what he should do. He could hardly let this wayfarer leave his house empty-handed, on the eve of Pesach of all times.

All of a sudden, he remembered something. From his waistcoat pocket he took his watch and gave it to the wayfarer with the white beard. He might still have time to sell it and buy what he needed for the feast day.

The man thanked him and left without a sound, the same as he had arrived.

A few minutes later, the rabbi’s wife entered the room.

‘What time is it, Nachman? I think it’s time to bake the chametz!’

‘I don’t have a watch anymore, Batya,’ replied the rabbi. ‘A wandering beggar came here and I gave him it so that he could buy what he needed for Pesach. I couldn’t let him leave empty-handed.’

For a long moment, the rabbi’s wife was speechless with amazement. But when she found her voice again, she yelled in a fury:

‘What are you talking about, husband? I saw no wayfarer enter or leave the house.’

‘If you didn’t see him, it doesn’t mean he wasn’t here,’ said the rabbi gently.

‘But how could you give away that watch, for goodness’ sake? Have you forgotten it was a wedding present from my father, may he rest in peace? Do you know how expensive that watch was? My father, Moise the sandal maker, blessed be his memory, toiled till he was bent double, he scrimped and saved for years so that he could give his learned son-in-law Nachman that expensive solid silver pocket watch, handmade by a famous silversmith . . .’

‘You’re right, woman,’ stammered the rabbi, as if waking from a dream. ‘I forgot it was such an expensive watch . . . I’ll run after him, maybe I’ll catch him. He can’t have gone far.’

And Rabbi Nachman put on his wide-brimmed black hat and his caftan, his knotted walking stick, and hurried out of the house to catch the stranger.

Not half an hour passed before Rabbi Nachman returned, his face radiant.

‘Well, did you find him?’ asked Batya from the doorway.

‘Yes, wife, he hadn’t gone far.’

‘And where is the watch?’

‘What watch?’ the rabbi asked in amazement.

‘Didn’t you run after him to get back the silver pocket watch, husband?’

‘What are you thinking, Batya? That I could ask for it back when I’d already given it to him? I ran after him to tell him what you told me, that it’s an expensive watch, made by a famous silversmith, so that he would know not to be swindled when he sold it.’

The rabbi’s wife wanted to scream, to scold him, but her voice caught in her throat. All she could do was run to the kitchen and weep there, muffling her sobs, without anybody else seeing her. For it wasn’t fitting that the rabbi’s wife should be seen weeping on the eve of the feast of joy at the liberation from bondage.

And the evening of the Seyder arrived, the meal to celebrate Pesach. The candles burned merrily in the brass candlesticks. The table was laid with a white cloth, glasses, enamelled clay crockery; the cheap tin cutlery shone bright and clean. Rabbi Nachman, in his white caftan, sat at the head of the table, on a bench, resting on pillows like a king; to his right sat his wife Batya, wearing a headscarf of white lace, straight-backed, as dignified and solemn as a true queen of the evening; then their daughters, daughters-in-law, and granddaughters, each in order of age; to the rabbi’s left sat their sons, sons-in-law, and grandsons, each in order of age, and among them, the few wayfaring guests whom the holiday had found in the village.

In a loud, singsong voice, the rabbi began with the verse that opened the Haggadah, from the old book that recounted the miracle of the Exodus from Mizraim: ‘This is the poor bread,’ he began, pointing at the unleavened bread on the table in front of him, ‘this is the poor bread that our parents ate in the land of Mizraim! Let all those who hunger come and eat! Let all those who are needy eat their fill!’ Reaching this point, Rabbi Nachman felt the urge to make a pause, not even he knew why, and lifting his eyes from the book, he saw on the threshold of the open door the tall thin figure of the wayfarer with the tangled white beard, the clear blue eyes sunken in their sockets, the long weather-beaten bluish caftan. He stood there in the doorway, framed by the silver beams of moonlight from outside. Nobody had heard his footsteps, but the stranger stood there, waiting.

‘He has returned? But why?’ wondered Rabbi Nachman. ‘He had time enough to be far away by now, he could have reached the seventh village from here.’ He said none of this aloud, for one doesn’t ask a guest on one’s threshold, ‘Why have you come?’ The rabbi made a sign for the stranger to be seated at the table. No matter how crowded the table, there was always room for a newly arrived wayfarer. The rabbi filled to the brim a glass of wine, which was then carefully passed from hand to hand from the rabbi’s end of the table to the end where the newcomer had taken his seat. And they all sang, and they ate, and they drank of what the Lord Above had provided.

During the meal, Rabbi Nachman noticed that the stranger with the tangled white beard did not touch the glass of wine in front of him, even though it was more than a custom to do so, it was almost a mitzva, a commandment, to drink four glasses, or at least more than half of four glasses. It struck him as odd, but he said nothing.

Then, when they reached the fourth glass, Rabbi Nachman, according to the ancient custom, poured a large glass of wine, which he placed in the middle of the table: the glass for Eliyahu HaNavi, Elijah the prophet.

And the songs and the stories continued until late into the night. The children, the little grandsons and granddaughters, fell asleep, and Batya, the rabbi’s wife, dozed off, and then the guests departed to their homes in the village.

At the table remained only the rabbi, murmuring psalms, and his dozing wife. Outside, dawn light began to glimmer.

All of a sudden, on the threshold of the wide-open door, the warden from the synagogue and a few members of the congregation appeared and said:

‘Rabbi, it’s time for the morning prayer!’

By reflex, Rabbi Nachman slipped his hand inside his waistcoat pocket and brought forth his watch. He looked at the hands:

‘Yes, you’re right! It’s time for the morning prayer!’

And then he exchanged startled glances with his wife Batya. The watch! The solid silver pocket watch, handmade by a famous craftsman! How had it found its way back inside his pocket?

They looked at the place at the end of the table where the stranger had sat. It was empty. The cup of wine that had stood before him remained untouched. But the large cup for the Prophet Eliyahu in the middle of the table was empty.

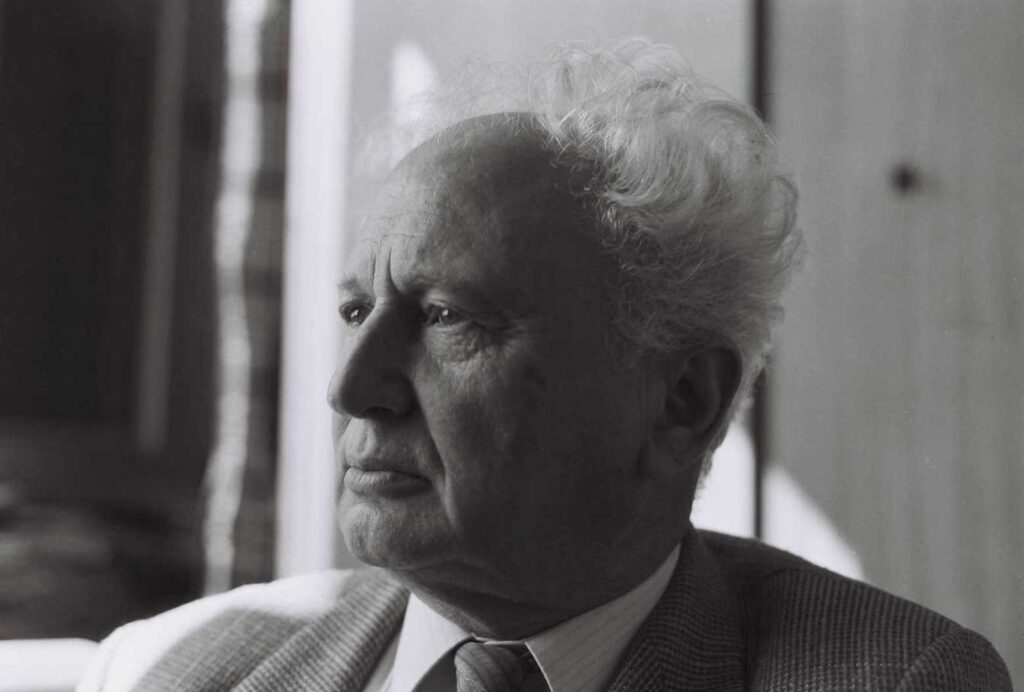

LUDOVIC BRUCKSTEIN (1920-1988) was born in Mukachevo (then Czechoslovakia, now Ukraine) but grew up in the Hassidic community of Sighet, Transylvania. Bruckstein’s father owned a small factory, and the family were traditionally Hassidic rabbis and writers. In 1944 the family were deported to Auschwitz, Bruckstein was then transferred to Bergen-Belzen and subsequently a series of forced labour camps. He returned to Sighet in 1945 where he found the only other survivor in his family, his brother Israel. His plan to move to Palestine had not come to fruition when the Iron Curtain fell. Bruckstein wrote plays in Yiddish and journalism for Yiddish newspapers and studied literature at Bucharest University, where he started to write short stories, before returning to Sighet. Twenty of his plays were staged, some were translated and performed in other Eastern Bloc countries. After years spent struggling to emigrate to Israel with his family, in 1972 he was finally successful. Between 1972 and his death in 1988 Bruckstein published seven books, a combination of novels, novellas and short stories.

The above story is from Bruckstein’s collection The Fate of Yaakov Maggid, due to be published by Istros Books in October 2023.

About the Translator:

ALISTAIR IAN BLYTH is a Translator with more than 15 years’ experience of translating from Romanian into his native English. His many translations from Romanian include: Little Fingers by Filip Florian; Our Circus Presents by Lucian Dan Teodorovici; Occurrence in the Immediate Unreality by Max Blecher; Coming from an Off-Key Time by Bogdan Suceava; and Life Begins on Friday by Ioana Parvulescu. In 2019, he was the recipient of a Modern Languages Association of America award for his work.