By Jana Juráňová and Agneša Kalinová

Translated by Julia Sherwood and Peter Sherwood

Purdue University Press

2021, 380 pages

In 2011 Slovak journalist Agneša Kalinová sat down with writer and publisher Jana Juráňová to carry out an interview that would range over her life in Slovakia during the First Republic, the rise of nationalism and the Holocaust, three decades of communist rule through her family’s emigration to Germany, followed by the fall of the regime and her perspective on the post-communist world. Besides being a penetrating account of the peaks and valleys of 20th century history in Central Europe, the interview memoir My Seven Lives (Mých sedm životů) allows for the possibility of relating to dramatic events and oversized personalities in a way that most books covering history simply aren’t capable of.

History is typically presented as information—the movement of armies, decisions of prime ministers or dissident leaders, etc.—or as a crafted tale in which the economy of storytelling edits out the stuff of everyday life. For most people, whose lives consist of raising a family, going to work, meeting friends, cooking, traveling, etc., a typical memoir seems to take place on an entirely different plane of existence, showing a life whose every moment appears significant or symbolic.

In My Seven Lives moments of high drama and tragedy co-exist effortlessly with everyday life. Kalinová grounds her momentous material so deeply in a world of family, friends, work and the ordinary that its joys, terrors, humor and sorrows feel closer to our own lives than they otherwise would.

Kalinová’s life began in Košice, eastern Slovakia in 1924. She grew up in nearby Prešov. Her account of her multicultural Central European youth, where Slovak, Hungarian and German-speakers co-existed, where an assimilated Jewish family such as her own were not set apart, makes the later rise of antisemitism and internecine hatred all the more shocking.

This picture of the world of her youth also belies the notion of social progress as linear, that prejudices come from the dark past and will be fought against and diminished going into the future. Because here a period of tolerance and relative harmony was followed by hatred and nationalist division.

Kalinová grew up in a household where her parents spoke Hungarian, she spoke German with her governess, she spoke Slovak at school and the local Šariš dialect during breaks. In addition to this she studied French from childhood with a family friend. This multilingualism and the more international outlook it gave rise to would prove crucial throughout her life as a translator, journalist and film critic, as well as when she had to escape the country to avoid deportation to the camps and much later when communist oppression forced her and her family to emigrate.

The rise of antisemitism in Slovakia and its government’s deportation of the Jewish population is an extremely compelling yet difficult part of the book to read. Kalinová was able to get to Budapest and take refuge in a convent. Her parents, along with numerous family members and friends, were less fortunate, perishing in the camps. My Seven Lives places these tragedies in the context of the overall divisiveness of the times, recounting how, for example, her Latin teacher was forced out of the country because he was Czech, how Košice was annexed by Hungary in 1938 and what that meant for people. It became a nationalist free for all and her perspective on it is sadly all too reflective of our own times:

“I thought it was just a display of the lowest of the low, but I wasn’t able to analyze it properly at the time. It’s always the same, isn’t it; populism can quickly hook the disaffected and frustrated, and then people join in who can smell profit and glory if they shout from the front row.”

The book’s interview form is highly effective in moving back and forth between the political/historical and the personal. There are even times when Juráňová’s questions compel Kalinová to reconsider or look closer at moments or issues she might have missed if she were writing her memoir on her own. When Juráňová asks her about the last time she saw her parents, Kalinová replies: “I have no recollection of a last exchange of glances, it’s all just a blank. In fact, I wasn’t even aware of this gaping hole in my memory until this moment.”

After the war, Kalinová got married and moved to Bratislava, where she describes having a few years of rich cultural life before the communist coup and crackdown. This was the period she began working as a journalist and film critic. “In the course of those first two or three years in Bratislava I accumulated more unforgettable moments than in my entire previous life,” she said.

Her account of the effects of the communist takeover are fascinating because, again, they are so grounded in her everyday reality and show a spectrum of personal reactions among her friends, acquaintances and colleagues, reflecting a hodgepodge of ambition, fear, envy, passivity, nobility, indifference, evil and large measures of chance and randomness. She shows relatively free-thinking people whose minds shut like a trap, generally less because of ideology than practical circumstances—to stand up against oppression would harm their careers or prevent their children from going to university. So they fall in line.

Kalinová recounts how the communists instituted a vetting process of undesirable elements, with people at work holding votes on which of their colleagues stay or go. Kalinová’s husband, Ján Ladislav Kalina, told her about the vetting sessions at the film studios where he worked and how during the voting process one of his colleagues was so cautious he wouldn’t give his opinion, saying instead “I vote with the majority”. Although aware of the absurd conformism involved here, Kalinová says she and her husband remained optimistic that communism would help put to rest the poisonous nationalism and racist hatred of the country’s recent past.

This optimism didn’t last long, particularly with the widespread anti-Jewish purges of the early 50s, yet Kalinová didn’t let anything dim her ability to laugh at the absurdity. Here she is talking about an ideologically-correct film version of a performance of Anna Karenina by the Moscow Art Theater from 1953: “I left the movie theater with the theory that this was Anna Karenina twenty or thirty years later: Anna was going through menopause, Karenin was impotent and Vronsky was an aging dandy no longer attractive to women.”

She also maintained a defiance not to give in to the spirit of the “grim 1950s”: “Never before and never after did we throw such splendid parties as in the years following the Slánský trial.”

The number of Slovak, Czech and international cultural figures Kalinová crossed paths with likewise makes for fascinating reading. Nobel-laureate Jaroslav Seifert, Ladislav Mňačko, Dominik Tatarka, Ján Rozner, Miloš Forman all receive mention along with Simone Signoret, Yves Montand, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, among many others.

All cultural activity aside, the harsh reality of the 1950s, with the informers, arrests and pervasive fear, was impossible to avoid. “This was when we got a glimpse into the mechanism of psychological terror and found out how people were pressured into incriminating themselves in the most absurd ways.”

The absurdity of the era is well-represented throughout the book. Kalinová recounts a scene of her husband rehearsing one of his humor-filled cabarets where the audience was filled with people from the censorship agency and students from the party school: “You couldn’t come up with a worse punishment for actors than to make them perform comic sketches in front of such a determinedly stony-faced audience.”

The Prague Spring is another period of cultural growth, though Kalinová points out the back-and-forth of liberalization and repression that characterized it. Like similarly rich periods before it was destined to come to a bleak and sudden end:

“Looking back on it, it was as if each of us had gotten on our respective bikes, mopeds and Škoda Felicias, and went hurtling straight into a dead end. At full speed. But it felt good, wonderful even, to be hurtling along and to believe that we were getting somewhere.”

The dead end was the invasion of 1968 and the period of “normalization” that followed. Kalinová shows another time of ideological musical chairs, where writers who had protested the invasion reassessed their possibilities and managed to acquire positions of influence in the “new system” by toeing the party line. For many others it was a new wave of purges and arrests. Kalinová describes she and her husband losing their jobs and how many of their friends began avoiding them. Their apartment is bugged by the secret police (ŠtB) and it isn’t long before they are arrested. Kalinová maintains that the Slovak authorities needed to arrest and purge people simply to keep pace with their Czech counterparts so their zealotry and dedication wouldn’t come under question.

Although she remained in prison for a relatively short time, Ján Kalina was sentenced to two years. Kalinová remembered the time after her husband’s release as “a single solid period, a seamless continuation of the steadily worsening conditions after 1970, when we were pushed to the margins of society, expelled from our original workplaces, and thus also from our social environments.” Unlike in Czech society, where intellectuals, professionals and dissidents were compelled to take blue-collar jobs, in Slovakia this work was withheld from people who were purged because it paid more than the low-level clerical work they otherwise had to do.

The examples of the authorities subsequent behavior range from the stupid—the ŠtB calling tow trucks to tow Kalinová’s car whenever the opportunity struck—to the cruel, such as when they blackmailed a young, widowed friend of hers to inform on her by threatening to take away her adopted baby. In the end, the friend decided to write the Kalinas and say she couldn’t see them anymore.

An additional burden was that their daughter Julia, who has so marvelously translated her mother’s book into English, was essentially forbidden from attending university. The accumulative effect of the harassment and prohibitions they faced caused the family to leave the country, deciding on Munich as their destination.

In Munich, Kalinová began working for Radio Free Europe, where she said, “we weren’t just there to condemn the regime all the time and draw attention to injustices, but to inform our listeners about what was happening in the world. That gave them the chance to compare the information and facts with the arguments the official media at home fed them, and realize how much they were being lied to.” She further emphasized how important this was for Eastern and Central Slovakia, which were cut off from German and Austrian TV.

When the Velvet Revolution arrived Kalinová’s joy was tempered somewhat by the realization that as the old regime “ended it was likely to bring about the end of solidarity and harmony between decent folk that had surmounted barriers of opinion and ideology.” Added to this was a resurgence in right-wing nationalism and the eventual division of Czechoslovakia.

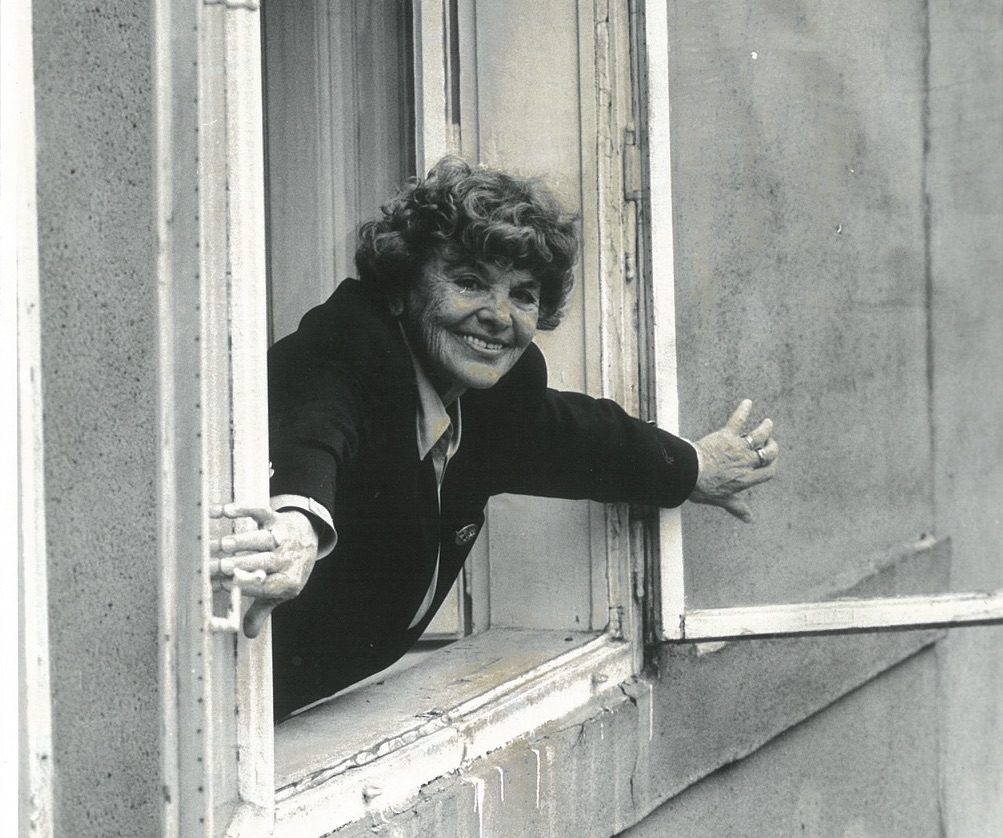

Agneša Kalinová passed away in 2014 but she has left behind an account of the darkest chapters of the 20th century that is as highly personal as it is universal, showing much of the light, humor and creativity that faced off against repressive conformism and hatred, and which continues to survive.

— Michael Stein