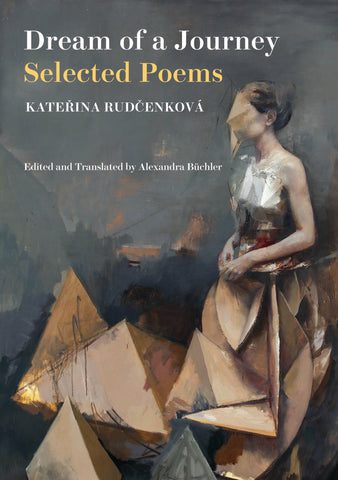

Dream of a Journey:

Selected Poems

Edited and translated by Alexandra Büchler

Parthian Books

2021, 120 pages

Dream of a Journey: Selected Poems, brings to readers of English the first full-length volume of poems by Czech poet Kateřina Rudčenková. Translated and edited by Alexandra Büchler, this selection from all four of her poetry collections, written over fifteen years, traces the evolving perspective of a poet living through a prolonged period of intense national change.

In Rudčenková’s earlier poems, we see a young woman who, skeptical of the future, wonders what will come. As she arrives incrementally at that future, she begins to look backwards, past childhood, into all that she has inherited. Eventually, her perspective turns outward, encompassing a more expansive and complex view of the world she inhabits. It’s a remarkable journey to follow. Yet it is in the details of Rudčenková’s evolution, rendered poem by poem, that reveal the emergence of truly a remarkable poet.

Rudčenková’s first two volumes of poetry, Ludwig (1998) and There Is No Need for You to Visit Me (2001), made her a breakout star in her own country, and reading these selections, it’s easy to see why. Her poems — mostly short, sharply observed lyric meditations — offer deft and savvy portrayals of the perils of both intimacy as well as private encounters with the self. By her third volume, Ashes and Pleasure (2004), Rudčenková’s attention is simultaneously deeper and more outwardly focused, probing the limits of the body and the spirit and the many ways they grasp for each other and miss.

Rudčenková’s fourth collection, Walking on Dunes (2013), for which she was awarded the Magnesia Litera Award, the Czech Republic’s most prestigious book prize, condenses her lived and imagined experiences into archetypes, visions that carry existential implications. There’s a grandness to that collection, which engages in philosophical discussions about what it means to inhabit a female body, but it is Rudčenková’s third collection that provides the greatest sense of intellectual and emotional intimacy — and lucky for us, it comprises the largest part of this selection.

In Ashes and Pleasure (2004), the striking minimalism of Rudčenková’s earlier work gives way to a more complex vision of the world. Here, the poems explore their imagined spaces more deeply and occupy more perspectives, offering a more expansive yet no less sharply observed view of the world. With an almost forensic intensity, Rudčenková explores her pain as well as her wonderment, both of which she renders with wit and precision. There is something comforting in these poems — the comfort that comes from inhabiting another’s mind, as well as the comfort that comes from knowing that another has suffered as you, and fears as you do.

In the poem “Come nightfall”, for instance, Rudčenková speaks bluntly about her fear of aging and points to the people around her: “I don’t want to grow old,” she tells us, “like the woman at the next table / whose lines are deep as the patterns of her partner’s pullover”; like the woman “whose hair resembles a wig / more than a wig could ever resemble hair” — an image instantly recognizable to anyone who lived through the hairstyles of the 90s. But Rudčenková’s concern is not merely the cosmetic effects of ageing, but rather what it means to be defined by one’s outward looks. Calling her own act of observing into question, the poem concludes:

all those radiant people and wrecks I among them

exposing my body to the sun

and my life to random explanations.

It’s subtle yet penetrating knife-twists like this that both elevate Rudčenková’s humour – the joke turned inward – and the potency of her observations. Great lines and underlineable passages abound in this collection. But Rudčenková is not merely a poet of observation. These are poems full of questions – neither rhetorical nor easily answerable – about what it means to exist in a world more easily seen than understood, and maddeningly difficult to articulate. Take the poem “Out of words” for instance, presented here in its entirety:

What if he looks

from behind different eyes?

What if time flows

faster in his body

and he has the spine of an old man?

The scalding sea washes him,

he no longer laments, just clings on,

The night is clasped inside him,

he is hammered out of words

and goes on hammering.

Rudčenková is not an ornate poet; her language is simple and direct. And for good reason: it is the only way to be understood in a world where words so often fail. The magic is in the way her sentences come together. The effect is an “enchantment of direct speech” (to borrow one of Rudčenková’s phrases), which, thanks to Alexandra Büchler’s unfussy translations, make most of these poems feel as if they might have been written in English.

Only in some of Rudčenková’s more abstract poems does the translation feel occasionally clunky, garbled by an approach that renders the more byzantine possibilities of Czech syntax perhaps a bit too literally. But these are minor quibbles; what we get from Büchler’s efforts is unfettered access to a poet of asute observation who perfectly captures the sensibility of the period and place in which her poems were written. A poet whose deeper, more profound observations make her not only an essential Czech poet to discover, but quite simply an essential poet for our times.

— Joshua Mensch