One of B O D Y‘s heroes told us “writers are readers first.”

The same is true for translators.

Herewith a fresh selection of our favorite recent poetry, fiction, and biography in translation from Ukrainian, Hungarian, Czech, and Italian.

— The Editors

Natalka Bilotserkivets: Eccentric Days of Hope and Sorrow

Eccentric Days of Hope and Sorrow

Translated by Ali Kinsella and Dzvinia Orlowsky

Lost Horse Press

2022, 207 pages

Poetry in translation performs a kind of shadow diplomacy, especially when the poet comes from a country as contested as Ukraine.

This incisive collection of four decades of poetry from Natalka Bilotserkivets, one of the most significant and most worldly Ukrainian poets, in compelling co-translation from Ali Kinsella and Dzvinia Orlowsky, is a crafted, measured, deeply felt, sober lyrical poetry of witness from her somewhat amorphous country.

Kinsella’s introduction draws intriguing connections between Bilotserkivets’ life and work and that of Langston Hughes, framing the Ukrainian poet as a kind of linguistic and cultural outsider whose literary contributions provide insight into other ways of living, thinking, feeling and writing.

These translations are bracing yet precise, expansive and particular. Here is the opening stanza of “Bridge”:

The air is as still and hot

as my body. Arched like a bridge

over a river. It’s so quiet—the nightingales

must be drinking their own black alcohol.

Perhaps Bilotserkivets’ most internationally renowned poem, “We’ll Not Die in Paris”, is included here. The poem alludes to “Black Stone on a White Stone” by the legendary modernist poet from Chile, César Vallejo, best-known in English through Clayton Eshleman’s translations. Vallejo’s poem famously opens with the declaration “I will die in Paris with a rainstorm” which expresses both the aspirations and failings of Vallejo and all modernist-minded individuals from around the world in the early 20th century.

In harmonious contrast, Bilotserkivets’ “We’ll Not Die in Paris” proclaims her (and her country’s) independence from Western and Eastern ideals:

…we’ll not die in Paris I know now for surebut in a sweat and tear-stained provincial bed

no one will serve us our cognac I know

we won’t be saved by kisses

under the Pont Mirabeau murky circles won’t fade

From Vallejo to Apollinaire to Celan, this poem from “Eastern Europe” ripples out through some of the most significant poets of western culture in the 20th century. The poem, which Orlowsky first translated into English in 1996, “became the hymn of the post-Chernobyl generation of young Ukrainians who helped topple the Soviet Union.”

Bilotserkivets’ poetry, in this crucial co-translation, is a bracing reminder of the sovereignty of our universal humanity.

György Dragomán: The Bone Fire

The Bone Fire

Translated by Ottilie Mulzet

HarperVia

2021, 480 pages

A gripping saga of a young girl in communist-era Hungary that is by turns dark, emotional and magical (literally). Emma’s trauma over losing her parents is paralleled to the historical traumas around her, particularly her grandmother’s from the Holocaust and the oppressive decades that followed. Is the magic the old woman practices a coping mechanism, or is it real? Dragomán creates his own form of magic realism that reveals plainly that the most ruthless and fearsome monsters come from humankind itself.

Kateřina Rudčenková: Dream of a Journey

Dream of a Journey:

Selected Poems

Edited and translated by Alexandra Büchler

Parthian Books

2021, 120 pages

This selection of poems by Kateřina Rudčenková, translated and edited by Alexandra Büchler, introduces readers of English to the work of an essential Czech poet. Rudčenková’s first two volumes of poetry made her a breakout star in her own country, and reading these selections, it’s easy to see why. Her poems—mostly short, lyric meditations—offer deft and savvy portrayals of the perils of intimacy with others as well as with oneself. By her third volume, we see a poet in full power as she explores the limits of her body and spirit.

Rudčenková’s fourth collection, Walking on Dunes (2013), which was awarded the Czech Republic’s most prestigious book prize, condenses her lived and imagined experiences into archtypes. There’s a grandness to that collection, which engages in broader philosophical discussion. What makes it work is her language, which in all her poems, is simple and direct, stripped of ornamentation. Rudčenková’s magic is in the way her sentences come together to form something surprising and new—a world smartly observed. And it’s in her deeper, more profound observations that we encounter an essential poet for our times.

Read the Full Review

Marco Santagata: Dante: The Story of His Life

Dante: The Story of His Life

Translated by Richard Dixon

Belknap Press

2016, 496 pages

September 14, 2021 marked the 800th anniversary of Dante’s birth, and with it came an outpouring of new translations and considerations of the timeless poet’s work. But this definitive biography by respected Italian novelist and essayist Marco Santagata was originally published in Italian in 2012 and was published in English translation from Richard Dixon in 2016. It authoritatively yet warmly captures the contours of Dante’s beginnings, inspirations, political career, exile and religious and philosophical occupations. From insightful explications of Dante’s universally famous poetic trilogy as well as his lesser-known sonnets, correspondence poems, and occasional writings, Santagata gives us a granular yet sweeping view of the poet and his seductively dramatic milieu of Guelphs and Ghibellines, sparring poets both secular and profane, and cocksure clans wreaking havoc across Italy. Dante’s peculiar genius is front and center, but what comes through most clearly is the legend as man in the world, making decisions, friends and enemies, writing words.

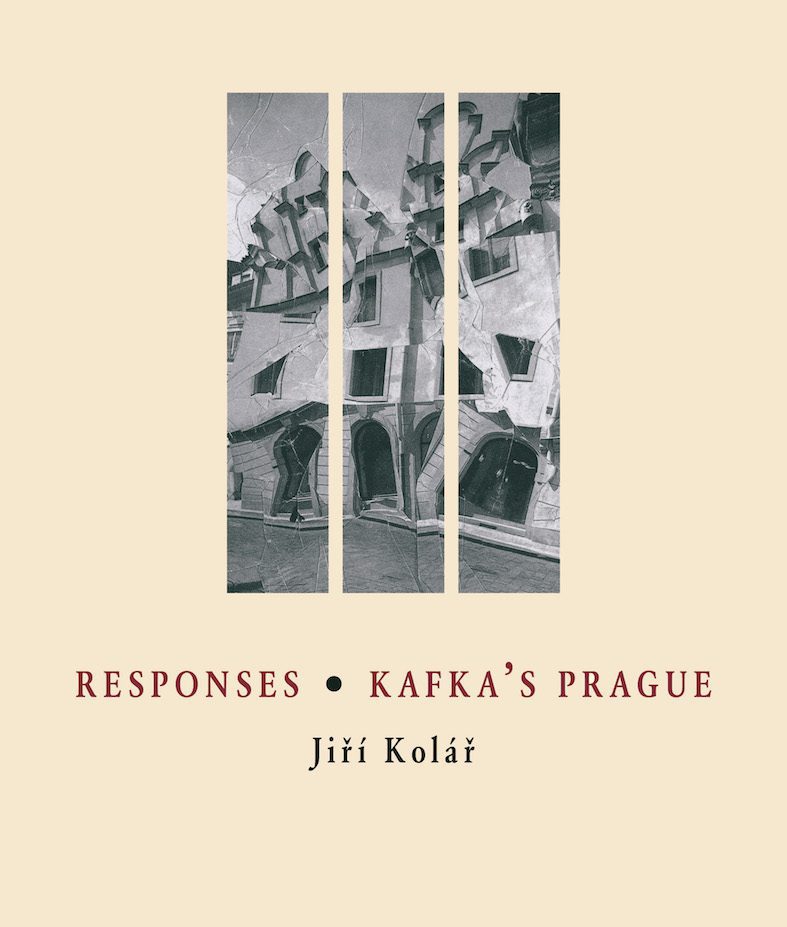

Jiří Kolář: Responses / Kafka’s Prague

Responses / Kafka’s Prague

Translated by Ryan Scott & Kevin Blahut

Twisted Spoon Press

2021, 133 pages

Jiří Kolář was a key member of the fermentative art and literature scene that flourished in Prague after World War II, despite the fact that it was largely driven underground. This book is delightful, starting with Responses, a collection of what Kolář called “imaginary interviews,” which he compiled in Prague and Paris in 1973. Translated by Ryan Scott, these are answers without questions, texts that meditate on art and existence, mixing autobiographical details with creative considerations of the art life.

The second part of the book, translated by Kevin Blahut, consists of Kafka’s Prague, combining fragments of Kafka’s writing with some of the finest examples of Kolář’s pioneering method of crumplage, crumpled pictures pressed flat, creating new, often hypnotically foreshortened images. These postcards from a literary and realistic Prague presage psychedelic rock posters and the shift toward materiality in western art and literature in the second half of the 20th century.

An insightful translator’s note from Ryan Scott provides just enough framework for Kolář’s precisely chaotic visual and verbal works, flights of focused fancy like a bottle rocket lit off in a high-rise housing project living room. As always from Twisted Spoon, the book is gorgeous, the editing impeccable, a beautiful volume that will warp perception.

Sandro Penna: Within the Sweet Noise of Life

Within the Sweet Noise of Life

Translated by Alexander Booth

Seagull Books

2021, 120 pages

Versatile Berlin-based translator Alexander Booth brings us this ravishing collection of lithe translations of the Italian poet Sandro Penna, spanning this significant 20th-century writer’s life and career, with poems from Poesie 1927–1938 to the posthumous Il viaggiatore insonne 1977. Penna’s earliest poems pack a punch of precocious modernism tinged with the Mediterranean romantic:

Life . . . is to remember waking

Sad in a train at dawn: having seen

The uncertain light outside: having felt

In your broken body the virgin

Stinging melancholy of the bitter air

The later poetry strips itself of emotional artifice while retaining its urbane sensibility and a kind of everyman insight. The final poem in the book, untitled, is dedicated to Eugenio Montale:

The frolic towards twilight I go

In the opposite direction of the crowd

Happily and quickly leaving the stadium

I look at no one and look at all

Now and then collect a smile

Rarer still a cheerful hello

And I no longer remember who I am

I’m sorry then to have to die

Dying seems too unfair

Even if I don’t remember who I am

Sweet noise from Penna and Booth. Poetry found in translation.

Recent reviews by B O D Y editors:

Stephan Delbos and Joshua Mensch’s Books in Brief (Fall 2021)

Stephan Delbos reviews Eileen Cleary’s 2 a.m. with Keats

Michael Stein reviews Carlos Busqued’s Magnetized

Stephan Delbos reviews The Selected Letters of John Berryman

Stephan Delbos reviews Mark Terrill’s The Great Balls of Doubt

Jan Zikmund reviews Jan Balabán’s Maybe We’re Leaving