ATOMIC CULTURE is a curatorial platform founded by Mateo Galindo and Malinda Galindo. They collaborate with artists on site-specific projects that reimagine the outlook of our cities. Mateo holds an MFA in Integrated Media Arts from Hunter College and a BA in Media Arts from the University of New Mexico. Malinda has a degree in Art History and Museum Profession as well as in Marketing and Communications from the Fashion Institute of Technology. Their past projects include, Re__ (2020), an online exhibition in two parts reimagine.site; State of the Artist: We’re Only Dreaming (2020), an election night in collaboration with Tri-city collective and ESP TV; American Ledger II. (2020), a site-specific score for Tulsa and the surrounding areas as Billboard by composer and artist Raven Chacon; Destroy the Myth (as vinyl window covering) by Demian DinéYazhi (2020); ´Ojalá at the Carlsbad Museum and Art Center (2018); Entre Irse y Quedarse at Galeria Merida in Merida (2017), Mexico; Future Now/Futura Ahora at the Loisaida Center (2017); and Turn on/Take Cover at the Carlsbad Museum and Art Center (2016). They were guest lecturers at The New School, Intro to Curating, and panelists in 2016 on Prefigurative Politics on the Eve of the Election at the Vera List Center. In 2019 they were invited to curate a booth at MECA art fair in San Juan, Puerto Rico. They’re currently running Cinetelechy Lab (an intergenerational storytelling mentorship in collaboration with Blackhorse Lowe) and Radiocoyote.org / 90.1FM, an online performance and community radio.

B O D Y: Have you always had a multi-disciplinary practice that includes making art and curating under the name Atomic Culture?

Mateo: Well, not until 2015. So, I guess before 2015 we were just kind of doing our own things, and dabbling in running DIY spaces.

B O D Y: Were you running DIY spaces together?

Mateo: With like maybe four other people in Albuquerque we were doing collaborative curating, and programming, lots of great experimental music. Stuff like that.

B O D Y: Where in Albuquerque?

Malinda: We started in 2009 with a space called Muy-Kind, and then moved to a spot in Barelas neighborhood, called Small Engine Gallery.

B O D Y: Is that before you went to New York, or had you already been living in New York together?

Mateo: No, this was in 2009-2010. I had never been to New York. Actually, I was just out of undergrad at the University of New Mexico, and just working at UPS, hanging out, playing, and recording music in Albuquerque.

B O D Y: Were you living there at the time, Malinda?

Malinda: After high school, I moved there to live with my Grandma. I had met Mat multiple times at different shows his band played. And he really introduced me to the New Mexico music and art scene.

B O D Y: Were you involved in the New York art scene before you came to Albuquerque?

Malinda: My mom is a curator. So, I grew up going to lots of shows and I went to a high school that was really involved in teaching arts education and using museums as a tool for learning. So I was immersed in art but I was just a teenager. I liked to go to see music, take photos, and cause a ruckus.

B O D Y: You recently did a residency at the Tulsa Arts Fellowship in Oklahoma – which brought you back to the South West. How was the transition from New York to Tulsa?

Malinda: I would say when we came here it was pretty exciting. We got to expand on different ideas which we had dreamed up and wanted to do. We were given the space, time, and money to develop these ideas and work with artists that we really wanted to have projects with. We were able to really rethink our practice and what we were doing.

This got harder during lockdown. When the pandemic started, it really did feel like you were in a different space, you know — the politics here are very different than ours. The way people responded to the pandemic was very different.

Mateo: But pre-pandemic it was more of like going back to the New Mexico speed and vibe of things. So, it wasn’t too much of a shock.

B O D Y: I was looking at your earlier work where your approach to curating was focused on futurism and the politics and aesthetics of futurism as a decolonizing tool. Is futurism still a part of your framework for approaching curatorial projects?

Mateo: I would say that, yes, but we’re interested in the different paths that the term gives. Right now, we’re doing a film mentorship program for ages 16 to 24. It’s centered on intergenerational storytelling. So, kind of taking that route.

Malinda: We are looking at deconstructing and reconstructing narratives, reimagining different outlooks, and opportunities for the different spaces where we’re in. This is something that futurism(s) can address. But the specific project that I think you’re thinking about was developed from a residency we did at the Loisaida Center in New York City. We were really excited about the parallels and the intersections between Chicano Futurism with Nuyorican and Indigenous Futurism, which was a topic that they were already exploring when we had started our residency. So, we were trying to think of ways that we could connect the two and how they intersected with the community that we were working within.

Mateo: I think we’re always thinking about the future and futurism, but just not maybe, like genre-specific or something like that. We are interested in how that concept can take on different meanings depending on who or what is doing the imagining.

B O D Y: Would you say activism is in itself a future-oriented perspective?

Malinda: This past year really pushed us into thinking a lot more about responsiveness and ways we can support both artists and the community. our bottom line to that was education, and how the arts can really help or change lives in different capacities. And so, we really pivoted. We do always see a public component, or an exhibition because that is also part of the practice. It’s also where the people you’re working with see their product. It can be really uplifting especially when you’re working with youth or different communities that don’t always get to see their work being shown in public capacities.

We also have been thinking a lot about the flattening of art education, the ways in which “Western Art” is taught, and again how we can add to the deconstruction and reconstruction of those teachings. There’s a lot of people that are doing that work already — artists and educators. We’re just here adding towards the efforts of that change.

B O D Y: Is that how your collaborative mentorship program, Cinetelechy, with Blackhorse Lowe developed – out of a need or desire to educate?

Mateo: It started off as a way to share art films in a drive-in setting. I grew up next to a drive-in (which is now a parking lot for an oil company) and always wanted to screen independent and experimental stuff in that setting. This led us to ask Blackhorse to co-curate a series. It just made sense to keep the screenings going, but install this educational model as well.

Malinda: We started Cinetelechy without the lab. When we got the opportunity to apply for an Integration Grant, we were already thinking about a few things, but it made the most sense to build off of a program we were already doing. We’re really fortunate to work with Blackhorse.

He brought in a great class of mentors for our pilot year, including Zack Khalil, Nanobah Becker, and Heperi Mita. Along with the mentors we are building a virtual curriculum of pre-recorded artist talks and readings. We’ve also partnered with Criterion Collection and they provided free access to their collection to the mentors and mentees throughout the duration of the program. This was an amazing asset for both the mentees and mentors to dive into. We hope to continue that partnership as the program expands.

B O D Y: How do you choose the mentees?

Malinda: Originally we would have had envisioned an open call, and for the program to take place in multiple cities, this would culminate in a week-long event in Tulsa with all the screenings and public programs, and some portion of that may happen in the future. But because of the pandemic and what we felt was necessary, we really cut it all down. We didn’t want to risk anyone’s health. And so, we pivoted, and we accepted mentees by recommendation. We reached out to high schools in and around Tulsa, community organizations, artists, and more… Our requirements were that they have an interest in film or storytelling and that they had an idea and permission from an elder that they would be working with. We ended up with four mentees from very different backgrounds. Some of them came from a High School outside of Tulsa that has a really great film program. But their previous experience focused on very strict or traditional styles of documentary work. and the others work in different mediums but were excited to use film as a way to connect the stories between the various mediums they and their family members work in. Cinetelechy Lab helped expand their thought process, ideas around what you can do with film or what you can do with storytelling outside of media narratives. We’re really excited that there will be a public screening of the mentors’ film along with the films made by the mentees or their trailers, depending on if they finish them in November. There will also be a talk about their films and their experience in the mentorship and while filming.

B O D Y: At the drive-in theater?

Malinda: November 4th and 5th at the Admiral Twin Drive-in Theatre.

Mateo: It’s a Twin screen – a screen on each side.

B O D Y: Speaking of Scott Kiernan from ESP TV — you recently collaborated with ESP TV on State Of The Artist. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about that.

Malinda: That was a year ago…

Mateo: That was wild because we didn’t know shit in terms of Covid. Scott came out and I was just, all nervous.

Malinda: And elections were coming up. And, you know, we’re in Tulsa. They had the Trump rally here, and they had all this stuff happening. And it felt really like a question of how were people responding to this, what was happening? and how was the whole artist community reacting to what was going on? We got inspired by Good morning, Mr. Orwell (the first international satellite “installation” by Nam June Paik, which occurred on New Years Day 1984, a one-time-only broadcast that brought together many artists). And reached out to ESPTV to see if they’d be able to do it. We were trying to do it virtually with them, which was even more complicated and the Drive-in theater doesn’t have WIFI. So, we were really fortunate that Scott Kiernan could come out to Tulsa. He worked with us and our collaborators, Tri-City Collective, live at the drive-in on the project.

B O D Y: Is Tri-City Collective a live stream video collective as well?

Malinda: They’re more like radio…journalism. Art and journalism. They have a really amazing radio show called Focus Black Oklahoma. One of their founders, Quarysh, has a background in TV as well. They brought in a lot of local poets and MC’s as well.

B O D Y: So, you had a live performance that was live-streamed and then simultaneously projected at the drive-in?

Malinda: It was a mixture of live and pre-recorded videos by artists.

Mateo: Kalup Linzy performed a rendition of Old Man Trump by Woody Guthrie live. We had a green screen and lights; we did the whole thing right outside of the projection booth.

B O D Y: I saw you were working with artist and musician Raven Chacon recently.

Mateo: In 2019 we commissioned Raven to create a site-specific piece from an ongoing series he has titled American Ledger, which are responses to the United States’ contested histories and the narratives surrounding the area that the pieces are displayed.

B O D Y: I’d love to know a little bit more about Raven’s piece. From what I understand, it’s a billboard, but also a musical score.

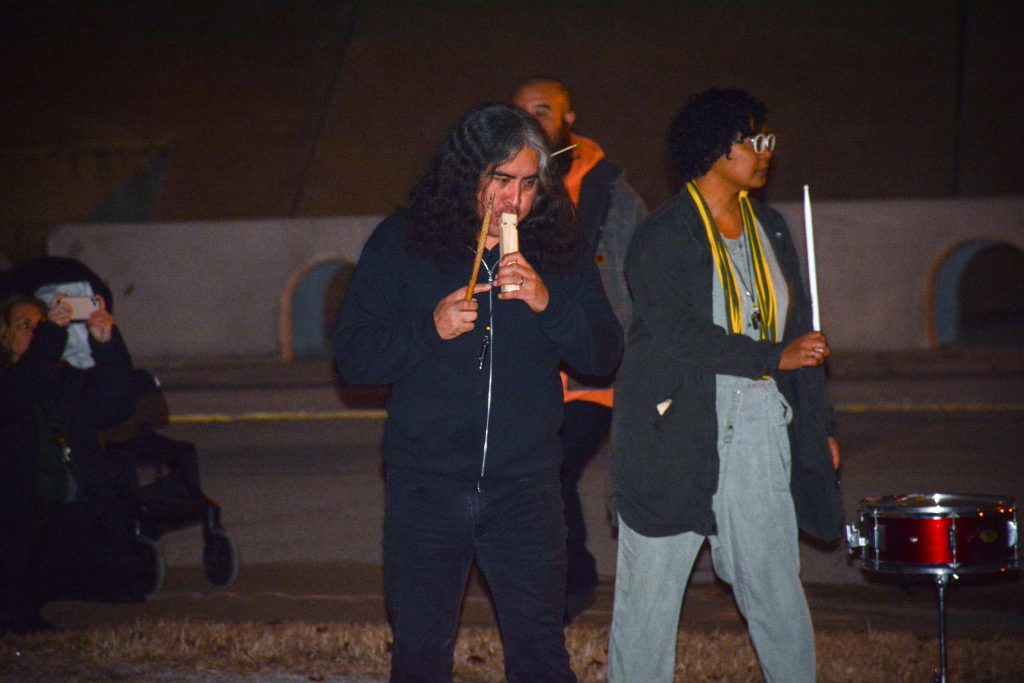

Mateo: It’s a conceptual graphic score that visually takes influence from the Oklahoma state flag and responds to the region’s history of forced migrations, both into and out of the city, in particular the 1830 Indian Removal Act and the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 and the current detainment and deportation of undocumented people. The score can be presented as a flag, a billboard, railroad debris, or any pyrographed object sourced from the region. This composition calls for drums, train and police whistles, megaphone, trumpet mallet percussion, and matchsticks. Raven has a really interesting way of using symbols in not only a musical way but also prompting an action or signaling a duration. It allows for both trained musicians and the general public to engage with his work in a collaborative manner.

Malinda: For the opening of American Ledger II, which took shape as a public performance in front of the American Ledger II billboard at the intersection of I-244 and Greenwood Avenue. We had an open call for participants, then held a workshop where Raven presented the piece and his vision then asked the group how they interpreted the graphic score, and what movements, sounds, and timing they envisioned. We practiced different versions until Raven and the group felt it was done. The work is flexible, and that is one thing that is so powerful about graphic scores and Raven’s work is how welcoming it can be to multiple groups of people regardless of their art or music backgrounds.

B O D Y: Is Radio Coyote a collaborative project with Raven as well?

Mateo: Kinda, he started it at a residency at the Wattis Center in San Francisco. After his residency, he wanted to keep the radio going. So he passed it to us and now we run it.

B O D Y: Is it 24-hour programming? How does that work?

Malinda: The new programs currently run in two-week cycles. So, every two weeks, we kind of put out a whole new batch of programming. And then within that, we have new programs or live performances or guest DJs.

listen to RADIO COYOTE

Mateo: When it’s not playing the shows, it’s freeform and it’s selecting from just basically experimental music, underground music, and different labels, like Raven’s label (SickSickSickDistro), he has, like all their releases on there. Music from Albuquerque from 2001 — noise music. Really cool to hear all that stuff that was originally released on like, you know, micro CDR or whatever. We’re also asking and looking for other independent labels, local labels to share some of their catalogs, Foxy Digitalis is a great example.

B O D Y: What projects do you have coming up?

Malinda: We’re working on a public art project here in Tulsa with the artist, Florine Démosthène. There are so many variables to it, because we are working with the city and multiple organizations, that I don’t want to say too much more than that we’re working on a public art project with her, and we’re really excited about that. We’re aiming for it to happen sometime next year. And then we’re really just focusing on Cinetelechy Lab, wrapping up this year and hopefully developing next year’s program.

Mateo: Nothing is set, so we’re just kind of waiting it out.

B O D Y: Do you have a little bit of breathing space in the waiting period?

Mateo: Not really, it’s pretty stressful.

Malinda: Matt works on his own projects, and I’m working on various different projects with other organizations. And so, the end of the year is never the downtime. January to March you feel – yeah, okay.

B O D Y: What are you working on, Mat?

Mateo: I’m doing a lot of sound work, continuing to record and work on different projects. Doing some video stuff, too. Just been kind of working slowly.

B O D Y: You just had your record come out?

Mateo: Yes, it’s called crieslol “Self Title”. A label in Tulsa called Peyote Tapes released some vinyl and It’s also on Bandcamp.

B O D Y: What was that process like?

Mateo: That was something that I started in like 2017, it’s just stuff that I recorded in different art studios and just wherever, you know … field recordings in the subway, in the desert. But it also has like lo-fi pop stuff. Basically my travels from 2017 to 2020. It was interesting to try and create a narrative mixing the two in that way.

listen to CRIESLOL

— Interview by Jessica Mensch