ELEANOR KING is an interdisciplinary artist working in installation art that responds to our physical, social, and economic landscapes. Her works have been presented at the Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto, Nuit Blanche, Franklin Street Works, Spring/Break Art Show, Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, and Diaz Contemporary, among others. She attended residencies at The MacDowell Colony, Yaddo, SOMA Mexico, the Banff Centre, and A.I.R. Gallery. Her work has been featured in Canadian Art, C Magazine, and Art in America. Eleanor is a Fulbright Fellow and received grants from the Canada Council for the Arts and Arts Nova Scotia. Eleanor holds a BFA from the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and an MFA from Purchase College, State University of New York, where she works in the School of Art+Design.

B O D Y: What are you currently working on?

Eleanor King: I’m working on a few things simultaneously. A couple of outdoor pieces, a possible sound commission, and ongoing studio experiments (which are mostly painting). I’m teaching, administering an art school, and living through a global pandemic like everyone else. The most imminent project is part of an outdoor group show called Owning Earth, curated by Tal Beery at Unison Arts Center in New Paltz, NY. There, I’m building an elongated beehive structure. The piece itself will be a tall tower of stacked beehive boxes, and it’s the first time I’ve had to engineer something to last in outdoor conditions (on a non-budget) so it’s been a new technical and artistic challenge. I’m planning to use the entire thing as a tall, skinny, four-sided painting surface, which I don’t tend to do when working when re-purposing sculptural objects. The show was of course delayed a year, so it is exciting to have it finally come to life.

This piece was inspired by Thomas Seely’s research in wild bee colony behavior. He suggests how beekeeping practices could be adjusted to suit bee colony preference and to safeguard their health over human convenience. In his book, “Honeybee Democracy”, he describes the bees’ collective process when migrating to a new home, which influenced my thinking about how we might learn from their swarm intelligence when protecting our own ecosystems and fragile democracies.

B O D Y: That sounds really interesting! You’re one of the few white settler Canadian artists I know who has dealt with Canadian settler colonialism in their work. Has living outside of Canada (i.e., NY) changed your work?

Eleanor King: I live on the ancestral unceded territory of the Lenape people, and since being here, I have learned more about the histories of white supremacist settler colonialism in the US context which has helped me to see connections to the Canadian (and global) colonization playbook. Racist dominion over resources, money, and power is replicated everywhere and continues to play out in the global economy today. The impacts of race-based colonization are intrinsically connected to capitalism and the issues that most concern me; white privilege, the environment, labor, economies. There is a thread running through my work that points to the ways the commons are endlessly colonized for capital.

Living in NYC forces (nearly) everything to be commodified. As you know, it compels the artists to make paintings because there are no alternative income sources – as Canadians, we take for granted access to institutional grant funding and public healthcare. So, in terms of the work – I’m not always thinking so much about a place as I commonly have (when making a site-specific Canadian museum show for example), which often considers the economic and social conditions of particular regions of Canada.

B O D Y: In 2014, Sarah Fillmore, chief curator at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, described your wall paintings as a kind of “visual mapping and place-making/setting”. She was referring to your then-recent installations at the Southern Alberta Art Gallery and the Confederation Centre Art Gallery. These exhibitions were comprised of site-specific wall paintings. The patterns and colors (European White, French Silver, Deep Waters, and PEI’s Morning Breeze) you used recall the socioeconomic and topographical history where each museum is located. Is this a strategy you still use in your work?

Eleanor King: My last solo show with a theme of mapping was Inverted Pyramids and Roads to Nowhere at Kamloops Art Gallery in British Columbia, Canada. The inverted pyramid refers to the Highland Valley copper mine nearby, and roads to nowhere, specifically the dead-end logging roads. I’d say the paintings in my studio today are less about human intervention into a specific geographic landscape and more about the current political landscape and in reply to city life. They’re graphic and text-based, they’re signs with slogans that can’t be easily read. They obfuscate meaning by crisscrossing words and mixing up the figure and ground. This tendency of working with coded messaging has grown in tandem along with the growing fascism here (and everywhere). But I also stopped wanting to make art entirely, because of that fascism … It feels necessary to do more to fight it on the ground instead of through art, wanting to commit to other forms of social justice, education, and community instead.

B O D Y: I first recall seeing your text-based works at the exhibition that concluded your residency at A.I.R. gallery in Dumbo, Brooklyn. Your paintings cleverly recalled the green construction plywood walls you encounter throughout New York City. These walls are location markers of sorts — marking a place that’s in transition but also separating public spaces from corporately-owned spaces. What was your thinking behind introducing text to these surfaces and/or these spaces?

Eleanor King: Great observation. When you and I were coming of age in Halifax, Nova Scotia, those green walls usually meant stalled development, a covering-up of urban “blight”. I remember when they started up the city for the G7 summit in the 90s by adding crown molding along the top of a long-standing vacant lot at Barrington and George, haha. Here in NYC, green walls are a tangible sign of rampant gentrification (capital) moving through the city, which changes so rapidly, even just in the few years I have lived here.

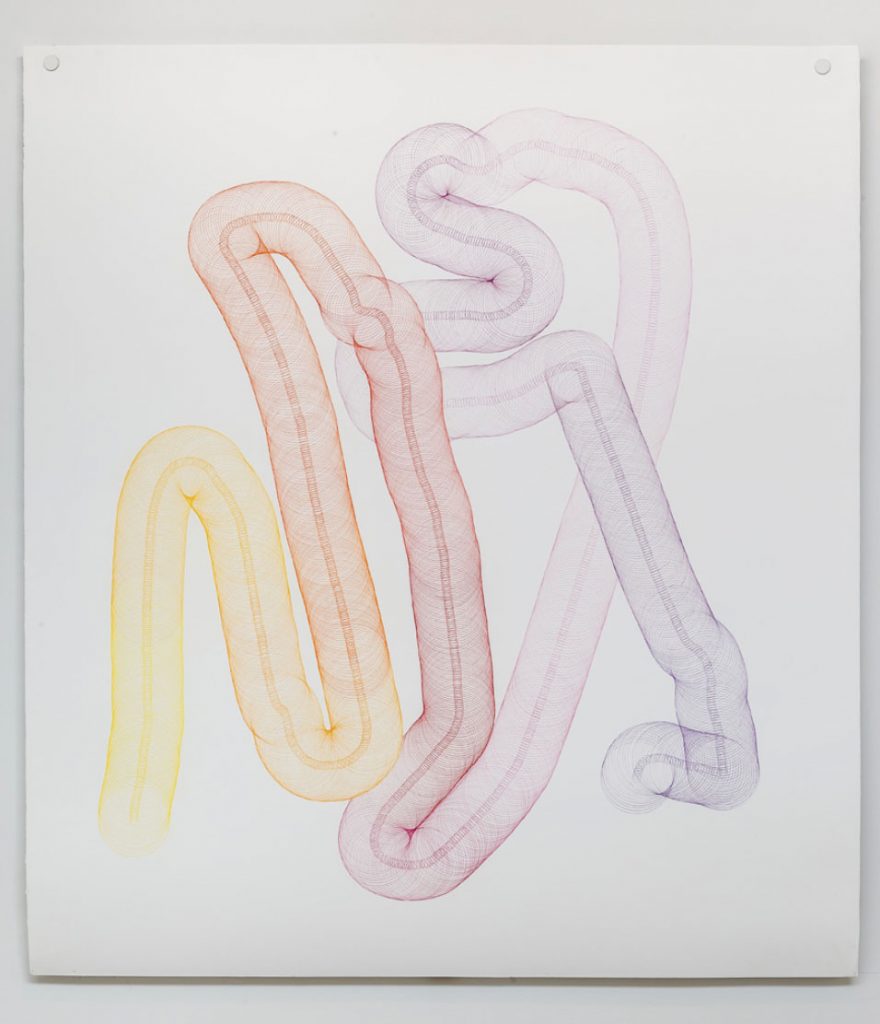

When I first arrived at Purchase College (NY) in 2014, Obama was president, Canada was still in the horrible Harper years, and Eric Garner had just been killed by the NYPD. Black Lives Matter, Peoples Climate March, and anti-ICE protests were happening. Being in solidarity with thousands of people on the streets — it felt angry and hopeful and real. I got criticism that my work was too “nice” and incongruous with my political fire. The careful, obsessive Wormholedrawings for example. I was trying to figure out ways to work faster and obviously say things more directly, but my perfectionist, Modernist (white supremacist) ideas of beauty and concept were always getting in the way, still always wanting to abstract everything. In SLOW DOWN / DONT STOP (2017) at AIR Gallery, the green wall component had been repurposed from my master’s thesis work. I wanted a substrate so I could re-use my labor. Having exhausted myself making these intensive site-specific projects, I was developing alternative methods in grad school to painting directly on walls. It also happened that the green wall piece fit EXACTLY on the diagonal, precisely bifurcating the A.I.R Gallery without needing to be resized. Absolutely magic! Unaltered but for the door cut into it, creating the new video space inside the gallery.

B O D Y: Where do you stand with your current painting practice in your battle between making something beautiful and making something that’s politically engaging?

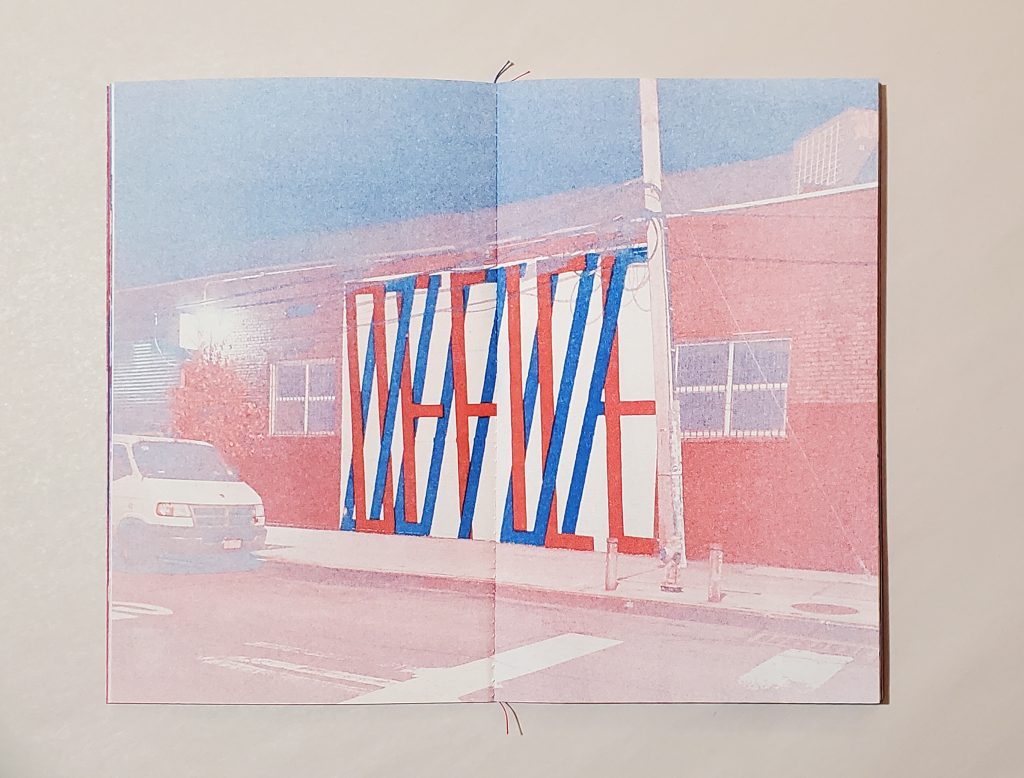

Eleanor King: I always battle it. My body just wants to make uptight stuff. I think I need painting to soothe the fire and despair; the act itself is a personal salve. When I’m painting it is maybe the only time my mind is calm and yet it feels so incredibly indulgent and stupid to make a painting in this political moment. Sometimes, I don’t know what else to do. My recent piece, OUT OF OFFICE (2019-20) starts as a small watercolor, literally an out-of-office reply — one of my favorite things in the world. Then, a demand to Trump, a spell in advance of his impeachment when translated to 20’ x 25’ painting on the side of a building in Brooklyn in September 2019. Made with Lucy Pullen at Level Foundation, the red OFFICE and blue OUT OF lean left and right, pushing and pulling. We made an artist book edition from the project which ended up being shipped to us from the printers on the day Trump officially lost power to Biden – a beautiful conclusion. Working on the street and publishing with Lucy was really a great collaboration which has continued into the project at Unison. I’m always excited when I get opportunities to make work in new ways. I had previously disliked using the word “mural” (because I’m a snob), but in this context, the Bushwick graffiti dude tours were stopping to talk about the work. I loved that! Using bright colors, visual punch and virtuosic scale have all been strategies to bring people into the conversation I’m trying to have, calling in instead of calling out. Also, making something beautiful and political shouldn’t have to be mutually exclusive. That sounds like a cop-out maybe. Anyway, these two ends of the spectrum visual/political spectrum literally manifest themselves in different ways. Slow Down / Don’t Stop was also a manifesto authored as a part of my written thesis, then published as an open edition poster on newsprint given away freely. The writing seemed a bit passé after Trump was elected in 2016 but then became even more relevant in the COVID pandemic; “Artists shall be grounded….”

B O D Y: I know some of your newer pieces have been painted on canvas. This seems like a development in your practice. Does it conflict with your politics?

Eleanor King: It turns out, canvas is simply the most practical thing to paint on if you want to move the artwork from one place to another. I’m always trying to find ways to make my work as portable, light, and logistically simple as possible, and I started making paintings on roll canvas as a way to make large banners (NO JERKS, 2017) or mural scaled works that could be installed quickly and didn’t require my physical presence (like (She’s come) Undone, 2018). I had initially started painting on walls in 2012 as a way to make the installation environment an ephemeral “leave no trace” kind of gesture, in opposition to my collecting STUFF to make sculptural installations in the earlier works. But eventually, I felt frustrated by my own trap of temporality and depleted after giving everything away. My first works on stretched canvas were just mock-up ideas for larger murals. Now, working on stretched canvas as the finished “product” makes me feel very insecure because it’s all so unbearably related to art history and the market which I find to be very annoying … and I have trouble with “painting” being the only context of a work. I never trained as a painter so I really struggle with technique — I don’t know when a painting that’s on an easel is done! Somehow it is much easier for me to paint an entire room than a 30″ x 40″ surface, it somehow doesn’t carry so much baggage.

B O D Y: Are you amenable to selling your paintings?

Eleanor King: I would totally sell them! Making paintings on canvas is the most straightforward way to make art that someone else might be able to have. And, as I said, I’m tired of always making things that disappear immediately. However, I haven’t yet shown any of this series, nor do I want to sell it, mostly because I don’t yet fully grasp this work and need more time with it. I also want to be careful not to fall into any binary categories including those of “selling” or “not selling” as a mode of being an artist. My experiences in public art school education were often underscored by this idea that you couldn’t “sell-out”, or that money ruins art, yet everyone wishes they had a solo booth in the fair or were represented by Zwirner. Or that you’re not viewed as a serious artist if you have another job. I try to address these contradictory messages in my own teaching. Talking about money and class is always taboo among artists and I’m bored of that — we all need money to survive and so many artists are only able to continue their practice due to their privilege (and/or secret trust funds). At a state school, we need to give middle- and working-class kids permission to go get it wherever they can, so long as it’s ethical. Speaking of teaching, my own privilege of working at art schools and in unionized environments has always funded me and my practice, and those positions make it so that the work doesn’t need to exclusively answer to the market. It’s slower because I maintain a day job, but I think it’s worth it?

B O D Y: Can you tell me about your recent choral work and what got you into that?

Eleanor King: Oh, yes I’m so happy about that work. The Kamloops Art Gallery was incredibly supportive, and I’m specifically indebted to curator Charo Neville who helped facilitate my most ambitious work to date and the subsequent publication. While producing the show, KAG connected me with the Kamloops Thompson Honour Choir who learned and premiered the piece, Take Days, 2018. This choral work was based on a pop song initially written and performed by Wet Denim (a Nova Scotian music collaboration with Victoria Parker, Jess Lewis, Leigh Dotey, and myself) and arranged for youth choir by Zach Catron.

The song’s lyrics had been written years before, and came out as a warning to not “steal from your future self” — both as a person making bad choices for your health and a society accelerating toward climate crisis. I imagined the choir much later; the Parkland shooting had just taken place; the anger of Greta Thunberg and youth movements were galvanizing. I had come back to NS for a much-needed break and I attended my nephew’s middle-school band concert and practically wept the whole time, seeing those kids perform with such joy. All of these things combined to inspire Take Days. I wanted the lyrics “DON’T SAY YOU DIDN’T KNOW IT WAS COMING” to be spoken by those youth, having their future sold out by our shitty environmental and economic policies, lack of gun control, and endless capitalist greed leading to an uninhabitable future.

We rehearsed at a day camp out in the woods, they were such amazing kids! We recorded at a proper recording studio which was a first-time experience for them — super exciting. The choir leader, Christy Gauley, was so incredibly enthusiastic and generous, the project simply would not have happened without her leadership. It felt like a mutually beneficial experience for everyone. I’m tearing up now just thinking about it because it was totally moving for me. They performed the work in person on two occasions in the gallery, and their recorded singing became the core sound material for the installation.

B O D Y: Do you want to keep working with kids?

Eleanor King: I think so! I really enjoyed that and would welcome another opportunity, especially to produce another choral work. A rewarding component of my other job is working with first-year undergrads, so a lot of my time is spent working with those incoming “kids” in a university art school setting.

*Listen to “DON’T SAY YOU DIDN’T KNOW IT WAS COMING”

Further Reading:

To see more of King’s work check out her website: http://eleanorking.com/