KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS is a New Jersey based artist, writer, performer, and DJ. His new series of large scale watercolor and ink cutouts will be showing at Night Gallery in March, 2021. B O D Y‘s Art Editor, Jessica Mensch, caught up with him over the winter to talk about his work.

B O D Y: I just listened to your audio piece, Hey boo, I’ve been lonely. What’s up with you?

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: I want to make another one. I’m working with a producer right now… I want to make an album. I’ve been talking to a bunch of different people about what it takes to make an album. I’m calling it an album but realistically it’s really gonna be very similar in format to what you heard. It’ll just be, like, original music. “Hey boo” had a lot of found audio and samples in it and I want to collaborate more on making original elements. I want to do some ambient tracks and then, like, blocks of spoken word, with different voices, with five different people or something, and record the same text and overlay the voices so that it’s this weird omni voice kind of thing going on. And then make some break beats and drum and base sets.

B O D Y: Did you compose the sound for Hey boo…?

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: For the last couple projects I worked with different producers and made sure the writing and editing was really good. So, the sounds that you hear is stuff that my friend Zahir did. We found sounds that had resonated with us from childhood and adolescence. We lifted sections of the Moesha theme song, the free jazz break from flying lotus’ “tesla” and juxtaposed that with tekken sound effects and then a lot of really fun Tascam sounds and open-source audio clips. It was very much a DJ set in its essence. I just mixed together the whole 22 minutes or whatever. I’m more of a mixer and writer than I am a producer.

B O D Y: There’s so much layering in your work, from the layering of sound in your audio piece, the layering of paper in your paintings, to your depiction of time – I often feel like I’m seeing multiple moments compressed into one.

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: I like that, that’s an interesting point. It might be just the absence of time that you’re picking up on. It’s kind of frozen in perpetual timelessness or something that makes it feel … I don’t know. I’m looking at the stuff I’m doing now and I’m, like, I don’t know where these people are in time other than right now.

B O D Y: The sense of space in your piece with the two figures and giant jellyfish reminds me of looking into a snow globe, where things move at different pace from ours. Where do your figures exist?

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: I’m thinking less snow globe and hyperbolic time chamber from Dragon ball Z. Let’s slow time down and focus in on what’s happening. I’ve been wondering about architecture recently, too, like, what does it mean for my work not to depict rooms or even full landscapes? And I’m thinking maybe the architecture I’m most familiar with has always been kind of oppressive. I think the linkage between movement and essential plains and space within the image allows for the focus to be on the manifestation of the space through the people that are there. Like, how does the person make their own space? Not just inhabit a space, but what does it mean for a person to exist and how does the space relate to that? Or something.

B O D Y: I sympathise with that feeling.

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: Most spaces exist before you do, and everything has a different function and a different rule. Most people don’t get to build their own house, you know? They just move into a box.

B O D Y: Do you know Kurt Schwitters’s Merzbau? He was a German Dada artist who modified a few of his apartments, redoing the interior architecture. His modifications were pretty drastic and disorienting, changing how you would function in the space.

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: They look really horrible to live in.

B O D Y: Ha! Well, one is called the Cathedral of Neurotic Misery.

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: This guy was going through it

B O D Y: I’m into it.

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: It’s cool as an installation or something but I don’t know if I’d do this to my apartment and wake up every morning and feel good.

B O D Y: I went to a wildness camp in Cape Breton for a couple summers where we lived in an octagon-shaped log cabin.

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: Were there windows all around?

B O D Y: As many as there could be. The ceiling was acorn shaped, coming to a peek at the center.

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: That’s dope. It’s interesting that you wouldn’t just make a circular building. Circular buildings have existed for a long time and I’m sure there are plans that exist. I love it when people have the ability to choose how they live.

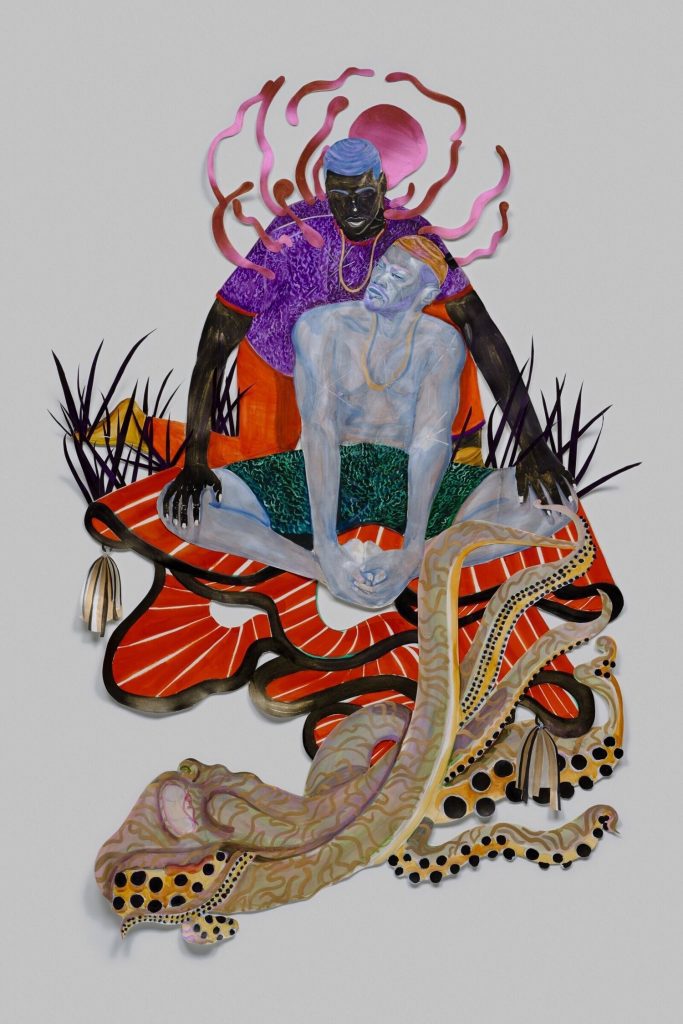

B O D Y: Yeah, it was an unusual choice. I’m curious about the animal life and vegetation in your work.

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: Well people are animals so maybe… I’m just wondering why humans have separated themselves so much from the “natural world”. But for me, I kind of think there’s always an animal doing something. Whether or not you notice it. Even if you’re in the city there’s a pigeon or squirrel or a rat or bug doing something. I feel like they should be included. They should have agency. The first time I ever really drew an animal in relationship to a figure in a work was when it was, like, a pet or something. But then there are animals that hang around that aren’t pets.

B O D Y: I see this purple guy carrying two frogs.

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: Oh yeah, that’s funny.

B O D Y: A lot of current portraiture and figurative painting attempts a kind of naturalism by sticking to what’s easy to get people to do, like sit in a chair, for example. But your figures are all in motion, they’re doing something.

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: Yeah, I’ve struggled with entertainment as a framework. I think a lot of figurative painting positions the figures to tell a story or act as an aspiration or portray power in this certain kind of way. So much figurative painting is about what a person symbolizes and for me I’m, like, struggling to figure out what it means to depict someone riding a bike or stretching in the morning or at a lake or something, just hanging out. And, like, it’s funny that a lot of curators will come in and say the vibe in here and the work are so happy. And I’m, like, yeah – most of the time I’m happy unless some dude does something fucking stupid or mean. You know what I mean? Most of my days I’m pretty fine unless something fucked up happens.

I listen to The Daily and I hear something crazy or whatever and then I have to readjust, you know? And I feel like, especially with figurative painting, there always needs to be this justification for why a Black figure is happy. Like, either there needs to be a justification for why the black figure is happy, like there needs to be a very specific occasion that people can place in our history, or, like, in the very specific entertainment realm, like, “oh these people are listening to records”, and “these are the records they’re listening to”, and “this is a depiction of like Sunday dinner”, or whatever kind of well-known tradition Black people observe. And I’m, like, actually there are these spaces, in-betweens, that are totally fine things to depict that don’t have anything to do with that.

I guess I’m interested in mundanity and magic or something. Last year I got really into Yoko Tawada. She’s a German/Japanese writer and she wrote this book called The Emissary which is like a really bizarre climate change novel about a guy who’s taking care of his grandson, but his grandson is getting old. Like his grandson was older than him. It’s a really bizarre story and her sentences are like ten words or less. It’s so concise and so poetic. There’s a book called The Bridegroom Was a Dog, which is about this lady who meets this werewolf and they have a bunch of sex and she finds out that he’s like married to this fox. The fox is like, “it’s cool, I don’t want him anyway”. It’s a messy story but it’s so poetic and so beautifully written and there’s so much weirdness going on. I’m like, how do I do that with painting?

B O D Y: Like, blur the boundaries we take for granted?

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: Yeah, but with simplicity. I don’t feel I need to make a wholly abstract or wholly psychedelic painting to depict the strangeness of living. There’s so much magic and strangeness that gets disrupted and I guess I want to capture them before the disruptions happen. So that’s where I’ve been with that.

B O D Y: Can you tell me about this figure in the overalls?

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: That’s my mom.

B O D Y: Is she wearing a spacesuit or maybe it’s a strange sweater?

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: She’s an ice fisher. There’s a sled and a big ass sunfish.

B O D Y: Oh, does she go ice fishing?

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: No, but I want her to. She’s always talked about starting a fish fry restaurant, so I wanted to do a fantastical painting of her as an ice fisher who caught a giant fish.

B O D Y: Has she seen it?

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: She came to the opening and I was surprised at how well of a job I did at depicting her.

B O D Y: I really like the pastel palette you used.

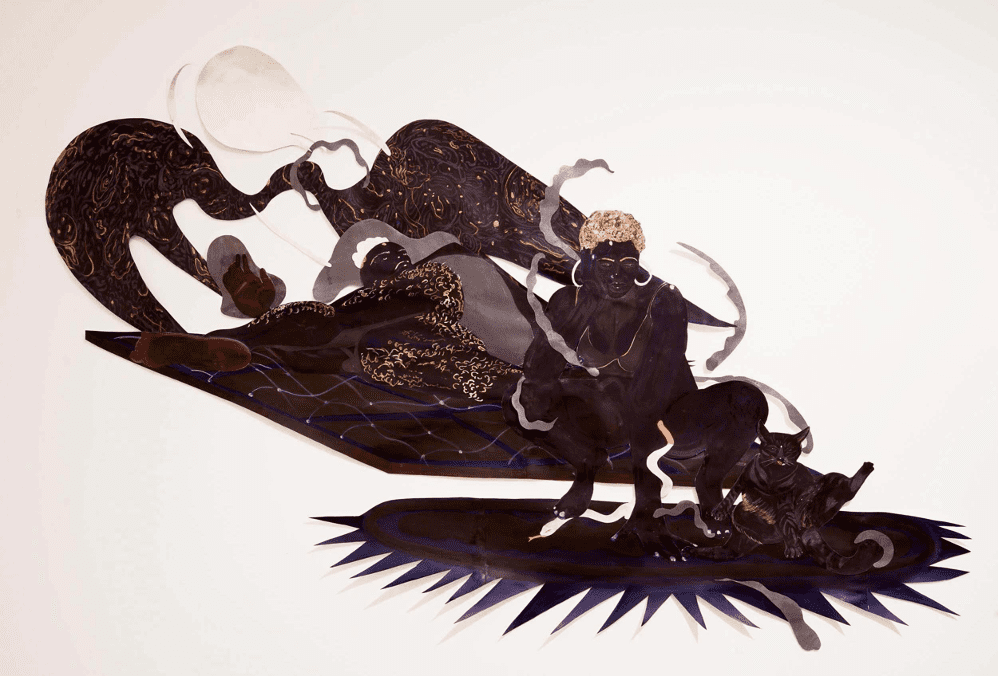

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: On a technical level I was trying to challenge myself to do a white painting. I ended up making a whole iridescent painting instead, but I think it still works. Recently, I’ve been trying to figure out ways to do paintings that are all one color.

B O D Y: Why is that?

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: I don’t know. My color education was all about harmony or something, so I kind of want to unlearn color harmonies, put the wrong colors together or make an all brownish-grey painting. What does that do? How do I show the values and chromatics of like a single color? I also really like iridescence, too. Not too many people do, they kind of hate it. I love them, I feel they’re underutilized and I don’t use them the way people normally use them, and they also just add another element.

I’m all about just using materials that I feel people turn their nose up at. A lot of people don’t have the skill to really use watercolor or ink, it’s too hard for them and paper is too unforgiving – once you put something down you can’t cover it up. I’ve been thinking about all the ways you can use these materials. The Western art tradition tells you that these are limited mediums. You can’t make a large complete work with them the way you can with oil paint. It’s always watery … but then you find out about these Persian miniatures and then it’s like, how did they do that? And nobody wants to tell you. That’s the thing that I want. And it’s really just a skill set. It’s like anything – oil painting or whatever.

B O D Y: So, you mix your own paints?

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: Yeah, I got a bunch of different pigments and stuff. I only buy pigments now from Kramer Pigments and I have everything in here – the shellac mediums and all kinds of stuff that I be playing around with. The shellac ink is different from the watercolor. If I want it to be opaque, I’ll use shellac ink.

B O D Y: Your pieces aren’t framed. They’re made out of paper, in many parts, and pinned to the wall. They’re delicate looking. Have you noticed people feeling nervous about showing them because of this?

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: Well, every time I have a studio visit with a curator or someone, they always give me the same spiel about framing my work or that collectors might be nervous about having my work in their homes. Every time I have a conversation with a new person, they go, “It’s on paper, why?”. It’s kind of goofy.

B O D Y: Your work has a lot of dimension – it pops out and folds over, etc. The grass kind of folds over like grass does when it grows too long.

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: Yeah, the best people to work with for me are people who think about ways to enhance the quality of the work, like, make it more dimensional and fluid. I have been working with Soull Ogun from L’enchanteur to make these amazing pins as a substitute for framing. They have different shapes and sizes and are often studded with semi-precious stones. That to me feels like an energetic that makes more sense for my work than a box to put it in. I’m really glad I’m working with brave collectors and gallerists who are not pressuring me to make my work fit into what might be the easiest for folks to understand right away.

B O D Y: Have you experimented with wall colors?

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: Yeah, I plan on doing that for my show.

B O D Y: When’s your show?

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: March 20th.

B O D Y: Night Gallery?

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: Yeah. “Feel Me.” Night Gallery, March 20th!

B O D Y: Do you have any zines that you’re working on right now?

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: I’ll probably start something in the new year. I just need some time. Like, that’s a whole body of work. I don’t have a whole separate body of work in my brain right now.

B O D Y: Returning to your sound piece, Hey boo, I’ve been lonely. What’s up with you?, I was wondering how that kind of storytelling relates to your paper pieces (if it does at all)?

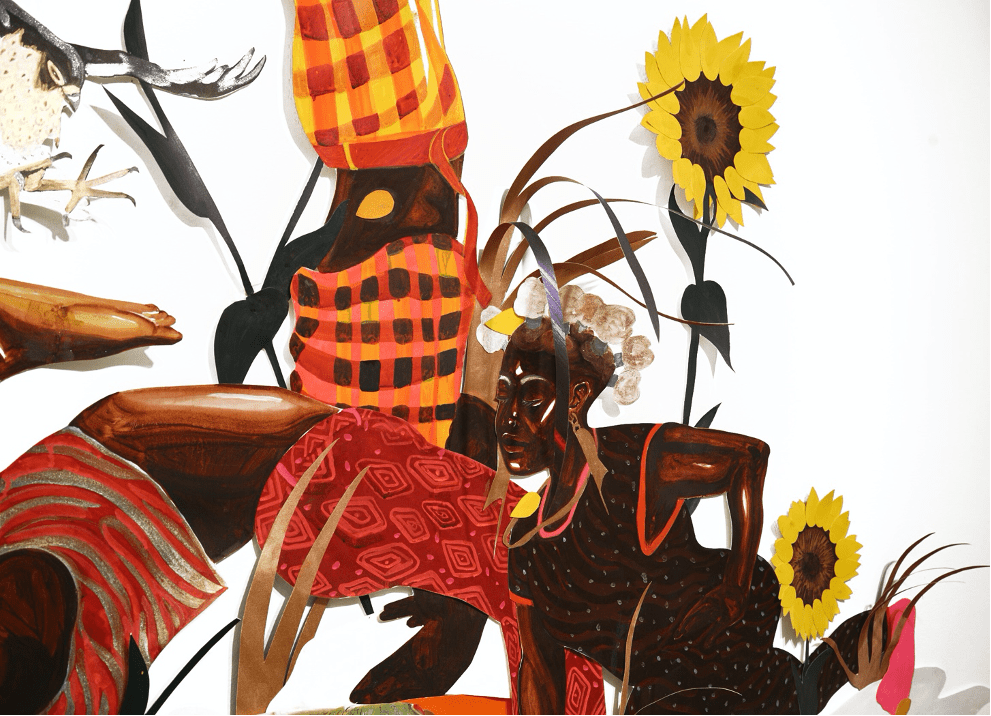

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: Well, the audio you heard is the audio for the performance in my MFA thesis – it was the same audio. It had a bunch of different relationships and purposes, but I think in relationship to the paintings, specifically, I feel there’s always a narrative regardless of whether or not it’s seen as an important narrative or something in every painting. Each text meditated on an important relationship and the lessons I had learned from that relationship. The painting with all the sunflowers, “Ants in my Juicer” was about the ways that people you love could inhabit spaces you don’t want them to and the architecture of boundaries. I was looking for ways to metabolize these schisms and find poetic ways to share them. All those pieces (in the sound piece) are less than 500 words. I think a few of them are 200 words. How do you make someone feel something in a minute and a half, two minutes, three minutes, versus spending an entire book building up a universe?

So, also, on a technical level it was a writing exercise for me. The stories were kind of like the glue between the performance and the paintings in the show because every story refers to a painting behind me, and the choreography of the performance was related to like a tradition that I had practiced over my life. Like these forms like – karate, and jersey club dancing. All these things that I had learned. There’s narrative implicitly connected to these things. And like what are those narratives for me? So, I wrote those down and paired them with the performance in hopes to use the movement as an embodiment of the text.

B O D Y: So, when you were listening to the piece and performing, did it change the way you performed those movement forms?

KHARI JOHNSON-RICKS: It’s interesting for me because within these practices there are barriers for how much you can change something. Like, in a couple critiques I had, they were like, “to a certain extent I see what you’re trying to do, the respect that you have for the form that you’re doing, but by taking it out of its context this becomes your work. So, what does it mean to build your own choreography from these forms and make a thing that’s specific to you, you know?”. I took that to heart.

For a long time, I would not ever change the karate moves, I would never do anything to bastardize the forms that I was doing, but you know this is just a language for how someone can move. So, once I turned it into a performance, it’s not about the tradition. And that’s what I took from the critique. I’m doing a traditional thing, but it doesn’t have to be about the tradition, and learning to be ok with that. Recently I’ve been trying to freestyle every night and see what comes out, without plans or anything. Sometimes it’s really good and sometimes it’s really bad. Hopefully a new performance will come out of me doing that all the time. Whatever, we’ll see.

–Interview by Jessica Mensch

Further Reading:

Khari Johnson-Ricks website: https://www.madebykhari.com/