IT’S SEPTEMBER, 1942, the Eighth Italian Army is camped just west of the Don River, preparing their latest counterattack against the Soviets in what will become known as the Battle of Stalingrad. On the other side a Russian soldier is undoubtedly carrying out reconnaissance, terrified of sniper fire, lying flat on the ground with binoculars pressed firmly to his face.

He’s risking his life to acquire vital advance information on enemy troop and artillery numbers yet his gaze is as transfixed as if he were a schoolboy staring at the girl of his dreams. What he is looking at so hypnotically has practically nothing to do with the war, a conflict that for the moment has altogether slipped from his mind. For in his sights is none other than the legendary founder of Futurism, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, in uniform and with a dagger sheathed firmly in his leather belt.

****

Marinetti’s first invasion of Russia took place almost three decades earlier, in January 1914, with the clouds of another war looming over Europe’s skies. In this case though, the head of Italy’s Futurist movement was mounting his campaign in the cause of the international avant-garde. It was an artistic, aesthetic invasion, but also one of well-planned and spontaneous publicity stunts and provocations. He came east seeking something between allies and followers in the hope that the Russian Futurists were on the same path as their Italian compatriots and were willing to acknowledge his leading role.

It turned out that many of them weren’t.

Poets Velimir Khlebnikov and Benedikt Livshits issued an anti-Marinetti leaflet accusing their fellow Russians of prostrating themselves before a foreigner, “…thus betraying Russian art’s first steps on the road to freedom and honor, and placing the noble neck of Asia under the yoke of Europe.”

Painter Mikhail Larionov’s broadside was less nationalistic and more explicitly Futurist, not unlike a provocation Marinetti might have penned himself: “We are arranging a gala reception for him. Everyone for whom Futurism is precious, as the principle of perpetual advancement, will appear at the lecture and we will pelt this renegade with rotten eggs, we will soak him with sour milk! Let him know even if Italy does not, Russia at least takes vengeance on traitors.”

Vadim Shershenevich was practically the sole Futurist among the literary delegation to welcome Marinetti at the train station. He would also go on to translate Marinetti’s Futurist manifestos, along with a couple of his literary works, into Russian.

Of all the Russian Futurists mentioned above, Shershenevich turned out to come the closest to meeting Marinetti on his second invasion as well.

****

We want to glorify war — the only cure for the world — militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of the anarchists, the beautiful ideas which kill, and contempt for woman.

– from the Futurist Manifesto, 1909

****

In 1942, Marinetti is sixty-five years old. He had fought extensively in World War I, been wounded and returned to battle. Now, this fighting machine is no longer a military threat and his value is evidently symbolic. Yet symbolic of what, exactly?

****

Marinetti was both the Malcolm McLaren and Johnny Rotten of his era, the impresario and figurehead of what was early 20th century punk. He charmed his audience with shock and provocation, telling his Russian hosts that the Kremlin was an absurdity, Tolstoy hypocritical, Dostoevsky hysterical, responded to a question about Russian art by asking if it even existed and going off about how women were inferior, and that of course the museums should be burnt down.

Many of the people who came to be shocked were shocked, others applauded this refreshing sense of disdain for the stale, decaying old order. The first lectures took place in Moscow on January 27th and 28th, 1914. Russian newspapers published a photograph of Marinetti standing at the lectern facing a packed hall. There is no air of mayhem. This well-dressed audience has come to listen to what Marinetti has to say, politely, to take him at his intellectual word, much like people today go to exhibitions of Futurists or read about their works and antics and go “Hmmm, interesting,” or “That’s too much!” and then go on to read about the Surrealists and their antics, or something else altogether, thereby missing the point.

****

If the Italian Futurists were like a punk band their Russian counterparts were more like intellectual versions of New York street gangs, with the appropriately catchy group names, bitter feuds and shifting allegiances. The only thing lacking was having their monikers emblazoned on the back of leather jackets as they prowled the streets of Moscow, Petersburg and more far-flung provincial haunts.

This assemblage of artistic, literary, intellectual futurist warriors included the likes of The Everythingists, The Nothingists, the Society of 317, the Jack of Diamonds and The Donkey’s Tail.

There were the Hylaeans, led by Vladimir Mayakovsky, Khlebnikov, Aleksei Kruchenykh and David Burliuk, aligned with painters such as Larionov, Natalia Goncharova and Kazimir Malevich. This inter-art alliance was eventually dubbed the Cubo-Futurists. Spurning the Cubo-Futurist’s objectivity for a more egotistical and sensual approach were the Ego-Futurists, started by Igor Severyanin, and later led by Ivan Ignatiev after Severyanin broke with his former comrades.

Then there was an offshoot of the Ego-Futurists called the Mezzanine of Poetry, counting poets such as Lev Zak, Riuruk Ivnev and Shershenevich, before he broke away and briefly joined the Hylaeans though his pro-Marinetti sympathies ultimately were too much for them.

Centrifuge was another Futurist group in the rumble, comprising Nikolai Aseev and fledgling pianist Boris Pasternak, then just starting to dip his feet in literary waters.

They carried out their rivalries through poetry, public disses in rhyme like today’s feuds between rappers, except slower of course, because they had to be printed, published and read. And just like the feuds between today’s versifiers these confrontations necessarily spilled over into real life. Pasternak describes a Centrifuge-Hylaean clash:

It was a hot day towards the end of May, and we were already seated in a teashop on the Arbat, when the three named above [Shershenevich, Bolshakov, Mayakovsky] entered from the street noisily and youthfully, gave their hats to the waiter and without dropping their voices, which had just been drowned by the noise of trams and carthorses, made in our direction with an unconstrained dignity. They had beautiful voices…

Besides being impressed by their voices and bearing, Pasternak notes how impeccably dressed the Hylaeans were compared to his contingent. The truth is, they were outmatched.

Suddenly the parley ended. The antagonists whom we should have annihilated went away unvanquished. Rather the terms of the truce which was concluded were humiliating for us.

****

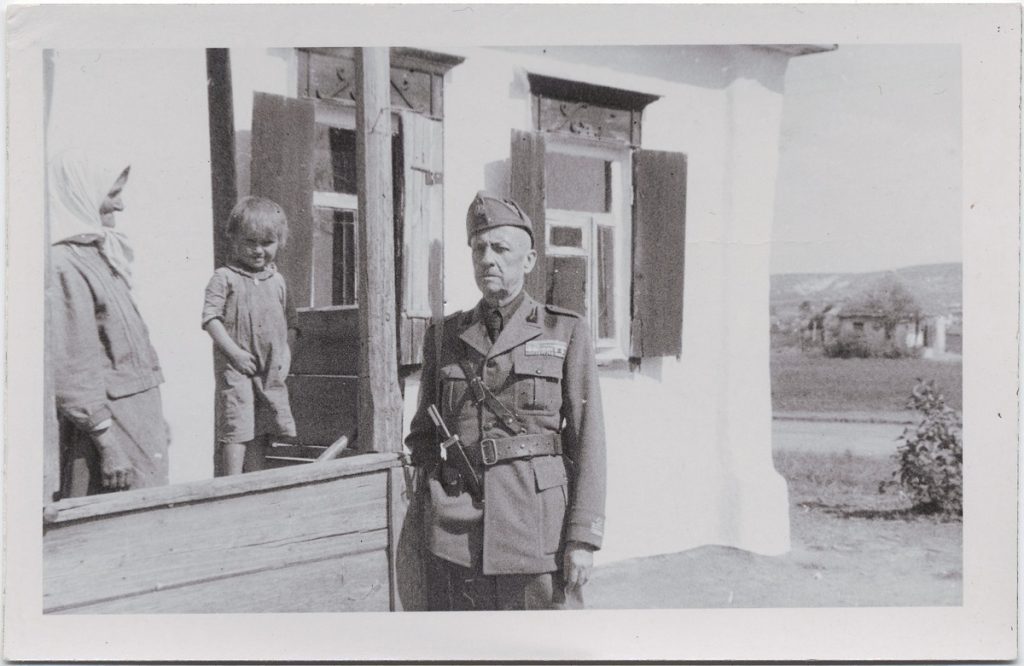

There is a photograph of the sixty-five year old Marinetti in uniform on the train headed to the eastern front. There he sits, the founder of one of the avant-garde’s groundbreaking movements, surrounded by beguiled listeners as he reads from a book in his hand. It’s an old black and white photo and it’s impossible to see what book he’s reading, so it’s also impossible to say whether it’s a work of cutting-edge Futurism or some patriotic dribble that would be more likely to please the group of officers and nurses seated in the train car around him.

Imagine the equivalent today: A unit of US marines are flying into Kandahar or Fallujah, and in the back of the cargo plane the troops and commanding officers listen to a former East Village underground poet read her work, a poet now wearing an officer’s uniform and armed with a pistol and dagger. One of the soldiers wants to tell the now gray-haired poet his parents had seen her perform with her band at CBGBs back in the day but decides it isn’t the right occasion to mention it. Punk, it turns out, is dead, but it’s been posthumously promoted.

This image is absurd, unreal, just as the image of Marinetti is absurd yet all too real. The anti-Catholic, internationalist innovator of the pre-WWI avant-garde had sworn to tear down the establishment. But now he was fighting for the establishment, was doing it in the name of the nation, of family, of God. And yes, here he was on a tearing down expedition. He was taking part in an unprecedented destruction – museums and culture included – but not quite the museums and culture he had taken aim at in his manifesto.

This Marinetti on his second and final trip to Russia was less like one of the early figures of punk than a bloated 70s rock dinosaur living on past glory and greed. Instead of cocaine he had fascism, and just like the rock megastars with their producers and managers he had the backing of a bald, fat megalomaniac.

****

On January 19th, 1914, just a week before Marinetti’s arrival in Moscow, Ivan Ignatiev got married. The very next day the leader of Ego-Futurism proceeded to attack his bride with a straight razor, that classic weapon of gang fights. She managed to escape, so he opted to turn his weapon on himself and cut his own throat.

Khlebnikov wrote about the incident:

…To the frozen path between stars

I shall not fly with a prayer,

I shall fly there dead, cold,

With a razor covered with blood.

There are the violins of a tremulous throat, one still youthful, and of a cold razor. There is the luxurious landscape of my darkening blood on the petals of white flowers. One friend of mine—you remember him—died that way; he thought like a lion but died like a lamb…

The honeymoon was over.

****

It turns out the future generally wasn’t kind to Futurists.

Khlebnikov wrote that he wouldn’t live past the age of thirty-seven and proved to be correct, dying of gangrene, in abject poverty, out of favor with the new Soviet government at thirty-six on June 28, 1922.

Mayakovsky famously shot himself in the heart on April 14, 1930, also thirty-six years old.

Of those who lived into the era of Stalin’s Terror, Benedikt Livshits never even made it to the Gulag. He was arrested in 1937 and executed in September, 1938. The Soviet authorities falsified his records to say he died of heart failure in 1939.

Igor Severyanin really did die of heart disease, in Estonia in 1941, having emigrated just after the Revolution in 1918. Though he made numerous attempts to return to Soviet Russia throughout the years he never made it back.

There were some Futurist survivors, but mostly in exile. Goncharova and Larionov moved to Switzerland, then Paris, just months after Marinetti’s 1914 visit and would never return. David Burliuk crossed Siberia, went through Japan and Canada, and ended up settling in Long Island, New York, dying in 1967 at the age of 84.

****

Another image, this one only preserved in words: Mayakovsky, Larionov, Goncharova and Marinetti are about to tramp into the Hotel Metropole bar when they come upon snowdrifts blocking the entrance. So the Italian picks Goncharova up in his arms and carries her over the piles of snow.

Marinetti was supposed to be attending a lunch in his honor that day but was waylaid by these three Futurist rebels telling him how much more Futurist it would be to cavort with them then go to a stuffy luncheon they were forbidden from entering. A true Futurist, he opts for alcohol and rebellion.

One irony of the Italo-Russian Futurist interaction is that beneath the very real artistic, social and political differences between the Italian and Russians, much of the invective seems only to have been part of the back-and-forth, a game – we’ll threaten to pelt you with rotten eggs, then let’s go for drinks.

Another irony, they end the day’s festivities with a toast. When Marinetti is asked if he’ll come visit again, he replies, “No, there will be a great war,” and that, “we will be together with you against the Germans.” The linguist Roman Jakobson, who recounted this scene in his memoirs, writes that “I recall how Goncharova, quite strikingly, raised her glass and said: ‘To our meeting in Berlin!'”

****

In his 1913 book Futurism Without a Mask, Shershenevich insists on the idea of poetry as inherently combative, that the Futurists are taking up a kind of mad fight, writing that “an army of clowns and jesters, turning somersaults and shouting absurd boutades, is rushing from Italy.” He explicitly states that Marinetti’s pleas to burn the museums aren’t meant literally, and it’s true that on that first invasion of Russia there was no actual burning or pillaging going on.

Shershenevich just missed Marinetti on his return trip to Russia, when the burning was no longer figurative and when a sixty-five year old invading soldier with his pompous poses and pretensions of fighting was serving as an altogether different kind of jester. The Russian poet had been evacuated from Moscow to Siberia with the Moscow Chamber Theater where, already suffering from tuberculosis, he died on May 18, 1942.

****

When Marinetti returned from the Russian front in November 1942, he reportedly told his friend the fellow Italian Futurist Alberto Viviani that “only the Russians, the Japanese and a few genius Italians, including [writer, Ardengo] Soffici, understood futurism.”

Perhaps behind the war enveloping the world there was another war, one between Marinetti the Futurist, the avant-garde provocateur, innovator and ruthless critic of smug bourgeois pretension and that of Marinetti the praise-seeker, movement leader, lover of crowds and bold declarations. Just like the military war, this war was reaching its tipping point. The Futurist side of him was on its last legs, but in that acknowledgement of his Russian comrades of long ago, of a people he had just participated in slaughtering millions of, there was a glimmer of the Marinetti of old, a last desperate radio broadcast as his former self is overrun by the forces of his victorious identity.

****

The Russian Futurists famously wrote in their 1912 manifesto A Slap in the Face of Public Taste to “Throw Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, etc., etc. off the steamship of modernity” yet those Russian bards are chugging along into the 21st century just fine, their books read, translated, re-translated, found in bookstores all over the world, their work adapted to the stage, television and cinema.

Steamships on the other hand have almost entirely vanished from the seas. These quaint, archaic relics are occasionally used as floating museums but otherwise the symbolism of that iconic phrase has taken on an unintentional irony.

Yet the contemporary artists and writers who attempt to define the cutting edge still often do so in Futurist terms with their manifestos and bold declarations, their shock and provocations, their performances and publicity stunts.

****

In October 1943, Marinetti wrote to Mussolini that it was his time in Russia that had provided his death blow: “My cardiac condition (a degenerative pulmonary edema) that I contracted in four months of war on the Russian front, has withstood until now the lacerating pain of seeing the assassination of Italy, you, and Fascism… But I no longer have the strength to walk and eventually return to the battlefields…”

As it turned it he didn’t get to see the actual assassination of Mussolini because his heart gave out first. Marinetti died of a heart attack on December 2, 1944. Il Duce was assassinated just about five months later.

****

From The Futurist Manifesto 1909:

The oldest of us is thirty: so we have at least a decade for finishing our work. When we are forty, other younger and stronger men will probably throw us in the wastebasket like useless manuscripts—we want it to happen!

They will come against us, our successors, will come from far away, from every quarter, dancing to the winged cadence of their first songs, flexing the hooked claws of predators, sniffing doglike at the academy doors the strong odor of our decaying minds, which will have already been promised to the literary catacombs.

But we won’t be there… At last they’ll find us—one winter’s night—in open country, beneath a sad roof drummed by a monotonous rain. They’ll see us crouched beside our trembling aeroplanes in the act of warming our hands at the poor little blaze that our books of today will give out when they take fire from the flight of our images.

They’ll storm around us, panting with scorn and anguish, and all of them, exasperated by our proud daring, will hurtle to kill us, driven by a hatred the more implacable the more their hearts will be drunk with love and admiration for us.

Injustice, strong and sane, will break out radiantly in their eyes.

Art, in fact, can be nothing but violence, cruelty, and injustice.

— Michael Stein