Magnetized: Conversations with a Serial Killer

By Carlos Busqued

Translated from the Spanish by Samuel Rutter

2020, Catapult, 179 pp.

The serial killer genre has never held much appeal for me. Neither the lurid fascination with blood and whatever else the murderers get off on, nor the statistics of their kills and captures, nor even the controversies over unsolved cases. I’ve seen some of the films, watched some of the shows, read a few of the books and some were worthwhile, well-done, much better than mere entertainment. Still…

When you read a book about a serial killer it is understandable to expect the dramatic stress to fall on when the trigger is pulled, when life is taken, or when the police close in and make their arrest. Then again, maybe it comes after years of imprisonment and psychiatric treatment, when the killer finally registers what he has done. This can be another earth-shattering moment, described with intensity and literary panache.

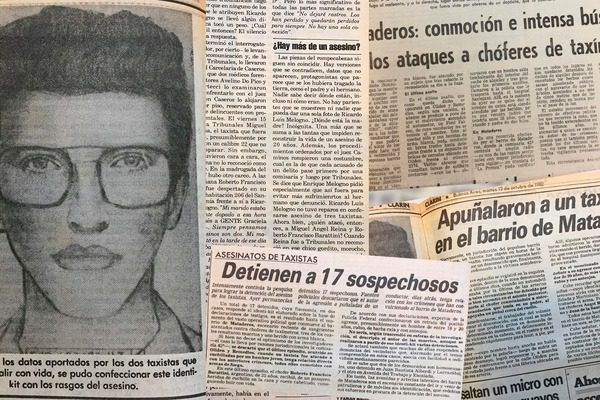

In Magnetized, Argentine writer Carlos Busqued tosses aside all these conventions to write a vivid, consuming and unnerving account of the case of Ricardo Luis Melogno, who murdered four taxi drivers in Buenos Aires in the space of a week in 1982. Melogno was nineteen when he was caught and put in prison shortly after the murders took place. However, due to a bureaucratic glitch, he remains in a state of potentially permanent yet undeclared imprisonment, a legal limbo the state has chosen to ignore.

The majority of the book is drawn from ninety hours of interviews the writer carried out with Melogno from November 2014 to December 2015 and is supplemented by a narrative account of the killings and Melogno’s capture, newspaper clips of the case, shorter interviews with therapists and the killer’s case files.

It is a singular narrative strategy, highly structured but not aiming for a conventional dramatic arc. In some respects it is reminiscent of a George Simenon novel, where the the identity of the killer is revealed right from the outset along with his ultimate fate. What’s left is everything else, and you realize that it’s this everything else that is what truly counts.

What adds to the effect is that the case is written about and told as the murders seem to have been committed, coldly and matter-of-factly, without the heart-pounding excitement writers usually aim for. When drama finally rears its head it becomes clear that the real mystery lies elsewhere and involves haunted houses, pharmaceutical torture, devil worship and forms of cruelty that make ordinary murder seem fairly quaint.

This Pandora’s box in the book is opened up when Melogno’s therapists mention his mother, a character long absent from his life. One psychologist asks him if he had ever thought of having his mother committed to a psychiatric hospital. Melogno says how, “Another time a psychologist told me ‘Ricardo, schizophrenics aren’t born, they’re made. And your mother did everything she possibly could to make sure you ended up with a severe mental disorder.'”

From there, the reader is brought into a world of warped spiritualism and tortured childhood in which the young Melogno would keep a knife under his pillow to protect himself against spirits. “My mother used religion as a weapon: she beat the living daylights out of me, but she’d say it wasn’t her who was beating me, it was God punishing me through her.”

A healer tells him as a child of his innate power but that he sees a darkness in him and that Melogno is “marked for the other side”. At one point he goes to Brazil to learn the Afro-American spiritualist practices of Santería, not out of faith but only to fight his mother. “I joined the cult. I was baptized in blood,” he says.

How horrible does someone’s relationship with their mother, their childhood, have to be that its description is so much more harrowing than the account of that same person’s serial murders? To read about the last time Melogno saw his mother or about whether he would consider seeing her now is harrowing.

In Busqued’s writing and Samuel Rutter’s outstanding translation, Melogno speaks with a clarity that makes it easy to forget he’s speaking about himself. He’s talking about his own childhood being taken away, his own emotional development destroyed at the roots and it’s as if someone were watching their own violent murder taking place on film and describing it dispassionately and in the most minute detail to explain exactly how they died.

For the assemblage of healers, con artists and lunatics surrounding his mother, “the other side” was the realm of evil and darkness, but there was another world Melogno was tempted to cross into to escape the misery of his daily life. This was a fantasy world drawn from movies and comics, something which everyone does to a certain extent, but which he inserted himself into to such an extreme that fantasy took over from reality:

“I crossed over because I was much happier on the other side. If I could have found food and shelter I would have stayed. I would never have come back.”

Some of the most powerful and poetic moments in Busqued’s book are Melogno’s coming to terms with this fantasy world, a world which he says began to disappear when he was in his mid thirties. “It’s like waking from a dream you want to get back to, but when you go looking for it you realize it’s too late…I thought it would last my whole life, because in jail a fantasy world is a wonderful tool, almost a necessity to mentally escape from where you’ve been confined.”

You read a book about a serial killer expecting to feel terror when he raises his gun or knife but here it comes in bursts of hard-earned self-insight: “I fantasized about being a person, which I never was in real life.”

Busqued has found a form and style which effectively renders this counterintuitive, alternative take on a serial killer, a perspective which isn’t at all just or even primarily the writer’s, but was also a realization claimed by Melogno during the killings themselves.

Looking at his first kill his reaction was, “How stupid killing seemed.” Busqued asked him why he thought this and Melogno’s answer shows he had seen the movies too, and expected something different:

“Because of how easy it was. How simple the act itself was. There are also these societal expectations, what you see in movies, that if you shoot someone and kill them, you’ll feel bad, you’ll vomit, you’ll have this huge oh-no what-have-I-done moment. I felt none of that; I didn’t feel any of those things that you’re supposed to feel, I just thought, “Is that it?” There was no special feeling of pleasure, or fear . . . nothing. I don’t remember feeling anything.”

— Michael Stein

More by Carlos Busqued:

Fiction in B O D Y

Review of Under This Terrible Sun in B O D Y

Interview in Asymptote