Waking in the middle of the night, I down a glass of water then plod off to pee, which seems funny enough to laugh about, but I don’t. Recently there’s been plenty to both laugh and cry about, but I haven’t. Just yesterday, I learned of the death of John White, a once close friend. (When you live abroad, as I do, there are times when “once” close friends—as opposed to far close friends—seem far more common than any other kind.)

When I shuffle back to bed my girlfriend asks what time it is. “One,” I say. (No need to say one AM—the night says it.) In fact, besides my girlfriend, I’m not sure I have any close friends. Only close acquaintances. She nods in the dark and turns away from me and the light of my iPad. (Upon which I’m jotting down the thoughts you are now reading, or even hearing being read. Believe it or not, I’m conscious of you, both of us conscious of the fourth wall breaking.)

John White was a good man. Set against the background of braggarts and swindlers that most people turn out to be—once you delve beneath the initial, cheap sheen of tinselly smiles and handshakes—John White was a very good man. Maybe even great. With his unchiselled jaw, and rather clenched features, he wasn’t conventionally good-looking. He’d never been the kind of guy who just strode over, brandished a smile, and got the girl. But, with his far-ranging mind and quick wit, he was the kind of guy that that very girl might become good friends with (if she didn’t happen to be the pretty, snotty type that avoided him as the proverbial nerd—John was, after all, assiduously bookish and studious) and brashly confide in about the boy she was currently pining for.

But since John had relocated from Prague to America he’d found the love of his life in a woman named Heather (an Australian English teacher, they’d actually first met in Stuttgart) and they’d gotten married. (Rumi wrote “Lovers don’t just finally meet somewhere—they’re in each other all along.”) They had two kids. One four-year-old, Vivienne, and one, Laila, just an infant. (I like to joke that people are much better at naming their pets than they are at naming their kids: I heard about a dude who christened his cat Captain Morgan; with spritely and elegant names like these, however, John and Heather had proved an exception.) I’d recently gotten reacquainted with John when I’d started conducting online poetry workshops via Zoom. (The damn Covid had to be good for something, and my English language student load at Berlitz had been severely diminished.)

John joined the group and, in his gravelly and nasally tone, regularly and astutely weighed in on his fellow students’ poems. John’s own poems were untamed stallions, stomping, whinnying and galloping towards an oasis of sloppy epiphany. Shifting metaphors, John wrote in bursts of passion that often seemed to geyser across the page, and gush into a reader’s dry head. But, in such bursts, punctuation and spelling could get neglected, and sometimes tangents sprang the eye of his passion down a highly personal trail that veered off the road he’d initially been going down in any given piece. (Sometimes the detours, turning up shimmering waterfalls of insight, made sense. Sometimes, turning up dull junkyards, they didn’t.) John was consistently humble, and honest enough, however, to accept our critiques and always did his best to rein in his stallions.

News of John’s battle with cancer percolated into the group during one of the assignments. (Considering the irrefutable proof of his illness’s seriousness, that John had just died, it was retrospectively remarkable how stoic he’d been.) Stricken with colon cancer, John wrote about the betrayal of his own body, bile erupting from within. As classes accrued, the topic of his illness came up more frequently, especially as his condition took a sharp turn for the worse.

And something else happened. (In a way both good and terrible, illness focuses us.) As John’s body got leaner (in a private message, John confided that, already semi-skeletal, he’d recently lost yet another thirty-five pounds), his poems got more focused too. Occasionally they galloped and geysered, but in a more refined manner. Gone were the extravagant tangents. Gone the pitched-at-the-edge-of-pretentiousness language games and intellectual diversions. In most cases, John’s word-stallions strode across the field of the page, spare and stately. As if, whipped by mortality, they’d been stunned into an awareness of just how gallant they could be, just by being themselves.

For instance, in one assignment, which was simply to jot down everything you did that day, and then compose a poem from the list, John conjured:

Sick for a Day

Muscles almost too weak

To pack an overnight bag

For the hospital.

Sitting on the floor,

I reach for socks and underwear.

Sitting on the floor,

I reach for my phone charger.

Sitting on the floor,

I reach for a book on Heidegger,

Put it back,

Then reach for it again.

His thoughts on authenticity

Keep me coming back.

This morning I had been purging my stomach

Of unnecessary contents

3-4 times.

Thorough like the TV show,

“The Art of Tidying Up”.

Unlike the TV show,

It did not give me pleasure to bid goodbye

To my foamy yellow bile

(It’s all I had left).

My mom came to pick me up.

She suggested an ambulance.

“That seems extreme,” I said.

We got detoured getting there

“I’m in no hurry,” I thought.

The staff in the mobile ER tents

Were in no hurry either.

Much later that night,

I’d get a cat scan (meow),

Then they’d stick a rubber hose

From my nose

To my stomach

To pump what remained.

I’d had the procedure a month ago

(it never gets old).

That irritant was hours away.

For now, I’m sitting in the shade

Watching the ducks in the pond,

The fountain jetting up,

And the emergency helicopter

Rise majestically into the blue

Banal of every day.

How tactfully sublime, that final image: “the blue/ Banal of every day.” And, in his last completed assignment, which was to take the opening line “I’m [enter your age] and I still don’t [fill in the blank, and keep going…] John wrote:

I’m 38 and still ignorant of the word “terminal.”

Terminal is a train station. Terminal is an airport.

Terminal is not the inability to scrape gew from one’s abdomen lining.

Terminal is not a Physician Assistant shaking her head sadly through her N95 mask.

But it is these things.

Terminal is an end point beyond which nothing can be done.

Except the flow of life that still breaths despite all odds.

A powerful piece. Especially now, I think. (Despite the typos of “gew” instead of “goo”, and “breaths” instead of “breathes.” A poetry workshop leader must sometimes be an anally-retentive bastard, or he or she will have nothing to say.)

Speaking of nothing to say, one of my most cherished anecdotes is about another great John, John Cage, who composed a piece called 4’33” in which the performer of the piece walks on stage, opens the piano, waits in silence for four minutes and thirty-three seconds, then closes the piano. A journalist asked Cage, “Why four minutes and thirty-three seconds? Was that just a random number?” Cage glared back and said “No. I counted every note of silence and it added up to be exactly four minutes and thirty-three seconds. I have nothing to say—and I’m saying it!”

In the dark, my heavily pregnant girlfriend, several days past her due date, sighs in her sleep. Never again will I speak with John, who had intimately described (hearing of his death, I scoured my inbox for a few old emails from him) his wedding to Heather in a message from 2018: “We walked down the aisle with a Swiss music box playing Ode to Joy, one of my favorite compositions of all time. The ring she gave me is tungsten steel with a band of abalone seashell around it because she knows I like intricate and colorful patterns.”

Intricate and colorful patterns of a steel ring. Intricate and colorful patterns of a stolen friendship, a stolen love, a stolen life. Intricate and colorful patterns of time and home and fate, weaving this gorgeous and merciless enigma: across an ocean, my dear friend has died while, across the bed, my new son awaits his first sunrise.

–Lucien Zell

_______________________________________________________________________

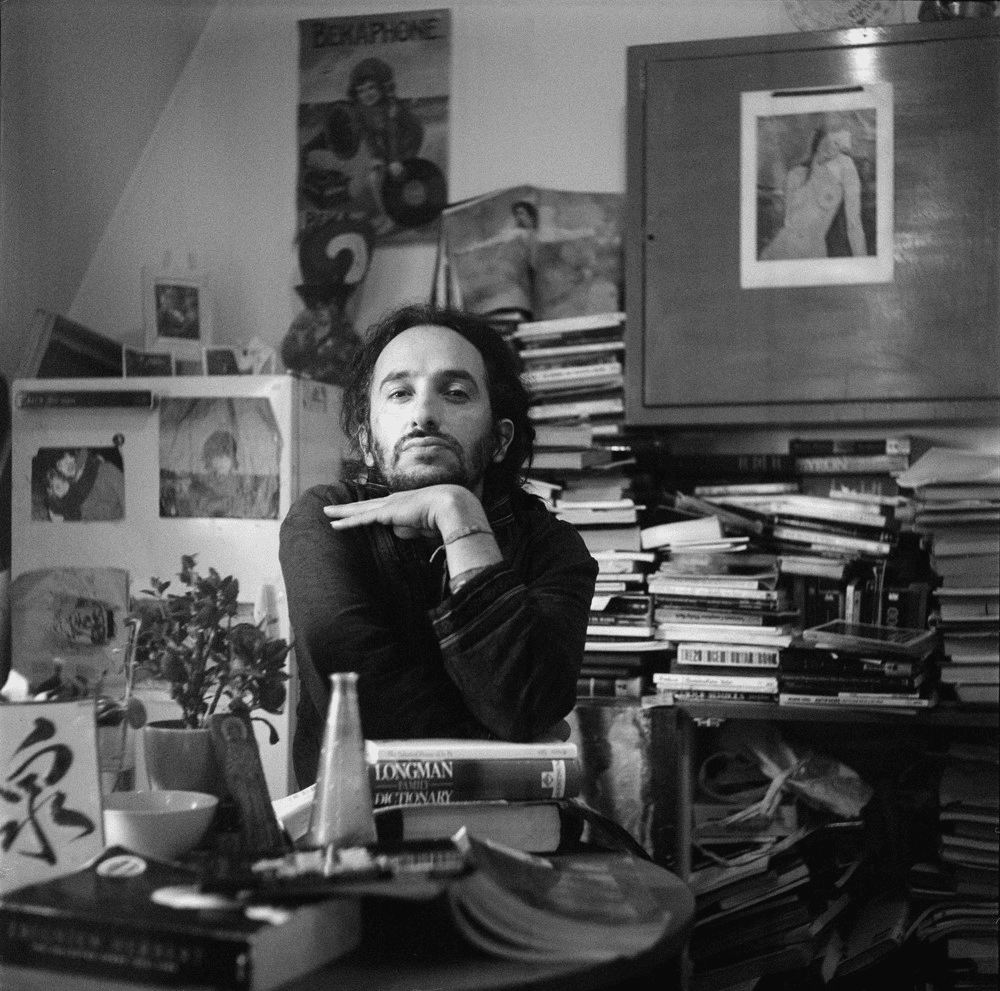

LUCIEN ZELL is a published poet and acclaimed singer-songwriter currently based in Prague. An American expat, his life experiences have taken him from his birth city of LA to Seattle’s U-District, to Greece and Israel, and finally to the Czech capital. His bibliography includes Tiny Kites (2019), Bright Secrets (2006), and The Sad Cliffs of Light (1999). Zell also acts, composes lyrics, takes photos and has been described in the Prague Post as a “Twenty-first Century Troubadour.”

_______________________________________________________________________

Read more by Lucien Zell:

Review of Tiny Kites

Poem in New Orleans Review

Two poems in Buddhist Poetry Review

Email Lucien if you’re interested in joining his poetry workshops.