MY BUTTON EYES

I have a big head. My face is flat and doesn’t have cheeks. I have button eyes. I cannot stand on my feet. Someone needs to help me walk, otherwise I will break at the hip and fall on my face. My hair is like the fringes at the end of the rug. I like the smell of Fati’s breath very much. I made her laugh and rubbed my face against the sound of her laughter.

When Fati used to go out with her father, she would leave me in my velvet blue dress, in the niche behind the window. Seeing the street, where among people, she waved at me would make me forget my inability to move my limbs.

It felt as if the window was hanging by a rope from the sky and I was swinging in between the buildings from one side of the street to the other.

One day, from that very same window, I was thrust into the street. The mirror on the niche came with me too, so did the bricks. With a sound that tore the sky, Fati’s mother was thrust from the room also. I was thrown onto the sidewalk, motionless. A few steps away from me, Fati’s mother moved her legs twice and then, just like me, with button eyes began to stare at the crowd. But, I looked over at the mosque’s minaret whose tall green body reached toward the middle of the sky. With the sound of Azan, the minaret caressed the back of a cloud.

People were running around me. Smoke was coming out of the house with the door wide open. The scent of burnt sugar filled the sidewalk. Beyond the smoke, a palm tree was on fire. The people who were carrying the dead and whisperings prayers were a lot bigger than the ones walking under my window just few minutes ago. Amongst their legs, I was searching for Fati’s shoes and her chubby ankles. The tiles on the minaret looked so blue that I was certain Fati could have not been crushed under their weight. My chin was still wet from her drool. (Every time she’d kiss my neck, she’d drool on me.)

The sun came down and there was still no sign of Fati. The next few days when people were leaving the city, no one who passed by would drip the smell of her breath on me. As soon as the city was empty, without opening or closing my eyes, I burst into tears.

I missed the sound of Fati’s mother’s sewing machine. On the day I was born, the smell of fried onion wafted into the room from the kitchen. The curtain leaning against the wind, walked to the middle of the room and brushed her lacey legs against me. Back then, I didn’t know that I won’t have any teeth and later I would be lying next to the open door of a house and watch the burnt branches of a palm tree for hours and days.

Sometimes, I would see a Saturday walk down an alley and slip into another. Right there, it would turn into the sunset and leave.

In one of those sunsets, a dog that was holding his left leg up in the air appeared from behind a bed that was turned onto its top in the middle the street. His toes had fallen off. He put his gray back against the wall in front of me, laid on his stomach and licked the wound on his paw. He looked at me with his eyes full of boogers. Then, he put his head down and slept till dusk. When it was completely dark, again, he put his gray back against the wall, held his left leg up again and slowly walked away. I was very scared. I talked to myself all night.

The empty streets in the next few days grew boring. I knew that my arms were stretched next to my shoulders and blue of my dress was fading.

One night, it rained for hours and the ground under me turned into mud. Raindrops seeped into my eyes. Water ran under me and the inside of my head got wet. Even when the sun came out, it took a long time for me to dry. Once, a strong wind blew that moved one of my arms. It tossed a shadow from the sidewalk to the other one across the street. Gradually, I got to know all the objects around me. The asphalt dragged itself on the ground and bent around the square. A young boy from the center of a poster glued to the wall wouldn’t take his eyes off me. My head had stayed on the ground for so long that I could hear the river pass under the bridge. I even heard a piece of metal come through the water for the first time. Then, sometimes later I saw a massive iron thing approach from the far end of the street.

On its face, it had a long pipe-like nose. Its iron legs were round, and it scratched the ground. It drove past my face. Behind it, a few men who were holding their hats like buckets were walking. They were not talking to each other. Only one of them was sitting on the iron thing and was yelling at the rest. He didn’t have Fati’s accent and didn’t know that the burnt palm tree and I were watching him. Behind them, two people were carrying a gurney with a man turned on his side. They went inside the mosque’s courtyard and put the gurney down besides the fountain. They lowered their heads into the fountain to cool off and wash their faces. Right there, they laid down for a rest. Later, without taking the gurney with them, they got up and walked away. The man who was turned on his side, did not move at all. I think he was looking into the ground. Sometimes I wonder if he, just like me, doesn’t have anything but the scraps of fabric inside him. The day people come back to the city, I’m sure, they will pick him up by the fountain. I say this, so you know where I’m lying down.

I’m talking to you, Fati.

_______________________________________________________________________

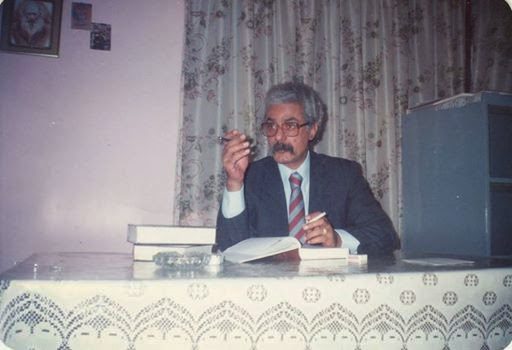

BIJAN NAJDI (1941-1997) was an Iranian writer and poet known for his collection of short stories, The Cheetahs That Have Run with Me. Najdi’s poetry and prose rich with elements of surrealism are considered some of the early experimental postmodern literature in Iran. They reflected the green and generous landscape of his hometown by the Caspian Sea and the Elburz mountains, as well as Iran’s struggle with revolution, war and modernity.

_______________________________________________________________________

About the Translator

PARISA SARANJ was born in Isfahan, Iran. She holds a BA in journalism from University of Massachusetts Amherst and MFA in Creative Nonfiction Writing from Goucher College. Parisa works as a freelance translator and editor, currently completing a memoir of growing up in 1990s’ Iran. Her writing and translations have appeared in several online publications, including Aslan Media, LobeLog.com, Your Impossible Voice, Empty Mirror and Nimrod International Journal.

_______________________________________________________________________

Read more stories by Bijan Najdi:

Story in Asymptote

Story in Exchanges: Journal of Literary Translation

Read more literary translations by Parisa Saranj:

Poems by Bijan Najdi in Empty Mirror

Poem by Bijan Najdi in Your Impossible Voice