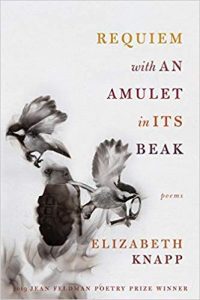

Requiem with an Amulet in Its Beak

By Elizabeth Knapp

Washington Writers’ Publishing House

2019, 73 pages

Reviewed by Francesca Bell

ELIZABETH KNAPP’s new book may carry an amulet in its title, but it will not keep you safe. Requiem with an Amulet in Its Beak is a dazzling collection, an expertly curated exhibit of grief and loss and questioning. Knapp thrills with her deeply imaginative, original perspectives, and she impresses with the deftness of her command of language and the skill with which she wields the tools of her poetic trade. But this is, first and foremost, a book of devastation, and its sorrow will sweep a reader into its current and carry them away.

In the title poem, the speaker states, “At night, I leave all the lights on in my head. / This way, I know the dead can find me.” And the dead will find you here. This is a collection of elegies, and laments, and the excruciating struggle to grasp death’s essence and parse whatever personal meaning can be found in its aftermath. Those left behind to continue the difficult work of living must grapple with absence, as the speaker does in “The Great Mysteries”:

Sometimes, when the wind blows a certain way,

I think I can hear the dead laughing.

All they have to do is open their throats,

and the leaves rattle, as the sky makes

a little pathway for their party.

Other times, it’s quiet.

The stars burn, but remain hidden.

They may be waving. Maybe not.

When we pay a visit to “The Cemetery … Full of People Who Would Love to Have Your Problems,” we are invited to “think of those poor souls who’d gladly give / their rotting right arm for [our] general malaise,” and in “Elegy with a Cameo by Linda Ronstadt,” we get the chance to pre-masticate mourning as we grieve, along with the speaker, the death of someone who has not yet died: “Neither of you was gone, / yet at that moment my own life // skipped, and for a moment / I heard its silence.” Knapp even gives us “Self-Elegy with Hand Grenade” which opens, “Like a pearl, or an egg, / it waits, my death,” and continues, “See me there / on the street corner // exploding myself / in the sun.”

Which brings us to suicide, a subject that seeps into many of the poems in this book the way that pollutants seep into groundwater. Famous suicides feature in the narrative in large and small ways. The focus of several poems, such as “Self-Portrait as Kurt Cobain’s Childhood Wound” and “Self-Portrait as Kurt Cobain’s Imaginary Friend,” is the Nirvana frontman. Cobain is a big presence here, as arresting as he was in his own life, “still strumming with desire and the karmic fears that kept him trapped inside the coffin of his body.” Anthony Bourdain and Robin Williams also make quiet, poignant (dis)appearances, and the speaker of “Threnody with a White Ford Bronco Inside It” loses her virginity to a boy who tried to kill himself once, while the speaker of “Koko the Gorilla Is Dead” admits, “That was / the summer I wanted to die.” Even poems about other subjects seem haunted by self-harm. “Lament in the Style of Monica Lewinsky’s Blue Dress,” for instance, closes with the line, startling in the book’s greater context, “Even the hangers are lonely.”

Though Requiem with an Amulet in Its Beak fixes its kaleidoscopic gaze over and over upon death, it also makes a close examination of life, in particular the life of a woman who is both a mother and a long-partnered wife. One facet of Knapp’s gift as a writer is her ability to get vividly, fiercely at one thing by describing something else. Directly following a poem about new motherhood comes “My Past Life as a Songbird” with these lines, describing the plight of a mother bird: “What did I have to live for? A nest full of hatchlings and a / drowned-out song?” And in “Song While the Children Are Napping,” Knapp muses about the thorny issue of whether a female poet should even write about the domestic life, “no matter how banal or uninspiring.” (It is worth noting here, as an aside, that, buried in this poem, as a fragment of a light-hearted line, is the phrase you nearly killed yourself, an example of how, no matter the subject of a given poem, the book’s theme of suicide lurks quietly in its pages, like a ghost.)

Of particular delight are five love poems marking each year’s wedding anniversary by riffing on that year’s traditional gift. These poems are tender, clear-eyed, and often very funny. In “Fifth Year: Wood,” Knapp’s speaker muses on the bonsai she has gifted her husband, so aptly describing a bonsai, children, and a marriage itself, “one more / ward under our charge (what do we know / of husbandry?), cutting back its wayward roots / and every year replanting. So much upkeep / required.” Anyone who’s made it through seven years of marriage will appreciate the wonderful ending of “Seventh Year: Wool”: “No delusions / here, and anyway, you hate wool: / something else to make you itch / for the life you gave up for this bitch.”

Some of Knapp’s finest work occurs when she widens her focus to survey our collective, American predicament and our planet’s problems, biblical in their proportions. In the sonnet “Black Friday,” even one’s sanity can be purchased at a 50% discount, and Walmart carries a Camo Barbie, complete with a pink AR-15: “Because we can’t get away / from ourselves fast enough, she observes, we let shiny / objects distract us.”

If shopping doesn’t do the trick, “Is That a Gun In Your Pocket,” another sonnet, offers an antidote to modern life along while making sly reference to Trump, our 45th president. “America,” the speaker says, “in one tiny fist you held a bottle of pills / marked Amnesia; in the other, a concealed .45.” “After the Flood” seems to look both backward, at a flood that has already washed over us, and oddly, prophetically forward, at a flood that is yet to come.

No one remembered the days leading up

to it—how the birds grew strangely quiet,

how the horses crossed the sudden fields

as if spooked by their own shadow, how

everyone went on about their business

behind the wheel in the kingdom of God.

An at-times crushing, always beautiful chronicle of sorrow and its afterlife, Requiem with an Amulet in Its Beak will haunt you long after you’ve turned its final page. With an adroit sleight of hand, Knapp uses playful surrealism and a profoundly expansive imagination to reveal our plain, damaged, human selves to us, helping us to “lean into despair / the way one leans into a mirror.”

– Francesca Bell