by David Biespiel

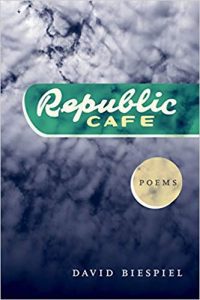

UWP 2019

81 pages

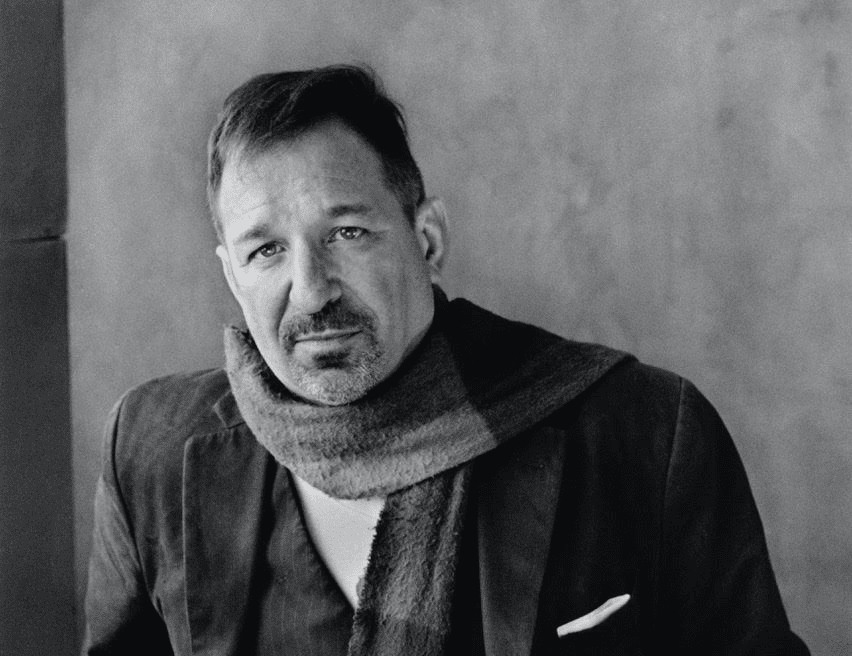

DAVID BIESPIEL is the author of six volumes of poetry, two memoirs, two essay collections, and is the editor of two anthologies of poetry. His latest volume of poetry is Republic Café, a long poem that recounts the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks from the perspective of a couple falling in love in the hours and days surrounding those events. A profound meditation on what it means to love in a time of terror, Biespiel’s poem explores the radical intimacy of public trauma and what it means to inhabit, within one’s own skin, the reality of the body politic. We caught up with David recently to talk about Republic Café and why he thinks “one’s most intimate feeling is always tethered to the world’s most hideous tragedies, including the intimate feeling of love or the intimate feeling of joy or the intimate feeling of remorse.” This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

_______________________________________________________________________

B O D Y

Your latest book of poetry, Republic Café, reads essentially as a single long poem, arranged as a sequence of fifty-four numbered sections. What was the genesis of this project?

DAVID BIESPIEL

One of the sources for Republic Café is the film Hiroshima mon amour, directed by Alain Resnais. This is a 1959 French New Wave film that stars Emmanuelle Riva and Eiji Okada, with a screenplay by the novelist Marguerite Duras. The narrative is fabulously anguished—about a brief, intense love affair after the Second World War in Hiroshima, about scarred memories, about love and suffering, about war and peace, and about memory. To get started writing Republic Café I studied Hiroshima mon amour: shot by shot, frame by frame.

There’s a case to be made that Republic Café is a cover of Hiroshima mon amour—at least in the writing of the poem. Once I was working with my own subject material—lovers in the American West, the tragedy of September 11, my private navigations of memory and forgetting, personal pain alongside public anguish—I didn’t think about the film much at all. I worked on the book initially in the fall of 2014, when I was back home in Texas for a month, and I finished it in the last days of 2018.

Why did you decide to write a long poem as opposed to a collection of distinct, self-contained pieces?

For as long as I’ve been writing poems, since my early twenties, I’ve had the ambition to write a long poem. Something of my first readings, I think, quickened that ambition. Poems like Dante’s Divina Commedia, Wordsworth’s “Two-Part Prelude,” Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” of course, T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, Crane’s The Bridge, William Carlos Williams’ Patterson, Galway Kinnell’s The Book of Nightmares, large swaths of Charles Wright’s poems.

All of these are lyric poems, no matter their length. I was attracted to that sort of big vision and oversized scale of a lyric poem. Something like Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale” on steroids. And especially the opportunity, the challenge, to sustain a single utterance over hundreds and hundreds of lines, and across multiple chapters.

Every time I set out with the intention to write a long poem, and I did so many, many times, my ambition, I guess, bumped up against a failure of capaciousness on my part. So, I mostly gave up the ambition to write a long poem or a book-length poem, or at least I forgot about it, or stopped perseverating about it. Even when I began writing Republic Café, I don’t think I was intending to write a single poem. I wrote scratches of lines, making and remaking scenes, that sort of thing, with the Resnais film as my ghost structure.

Best I can remember, it was my situating the narrative in the form of a journal, with a journal’s lanky, periodic nature, which the poem sort of talked itself into, that broke open the process and permitted me, if that’s the way to put it, to leave the film as foundation behind. What I found was: By writing in a poetic journal I felt free to say anything X juxtaposed to anything Y.

Form has always been an essential and singular concern of mine, though I think I’m less a formalist in the classical sense and more of an informalist. By form I mean, an announced vessel to contain the content. For instance, I composed all the poems in Wild Civility, my second book of poetry, which was published in 2003, in the form of a nine-line sonnet, a form I invented, if you will, and called an American Sonnet. In 2013 I published Charming Gardeners. All the poems in that book were epistolary poems. And so on.

Your publisher has described Republic Café as inspired by, among other works, Tomas Tranströmer’s Baltics, a long poem in which he examines his family’s history, intertwined with the broader history of his country and the land itself, as a kind of extended exploration of his own mind. How did reading Tranströmer — and this work in particular — shape the way you approached the twin themes of the September 11th terrorist attacks, a very public trauma, and the intensely private dynamics of an intimate relationship, which your book follows in the aftermath of that terrible event?

Tranströmer is such an important poet for me. He’s a refuge. His gift is to say something that always seems like it can’t be said—even after he’s said it. His poems are full of beauty and mystery. It’s like the wind can speak in his poems, or the darkness can, or the house that withstands both wind and darkness. His poems accept what is most spare about existence and transforms that into a luminosity.

Now, no one would go to read Tranströmer’s poems if you’re looking for other people, other human beings, in any sort of civic experience. There are hardly any people in the entirety of all Tranströmer’s body of work. And if there are, they are characterized as a multitude, as in a poem like “Schubertiana.” Throughout Tranströmer’s poems there is open land, endless sea, snow, wind, dark, light, and a solitary consciousness, a dreamy, clean, invisible consciousness.

I’ve always wanted to write like that—and fail at it again and again. Baltics is a special poem, the way Tranströmer journeys through archipelagos of all the things you mention in your question: fragmented islands of violence, splintered landscapes of faith, the shiver of dreams, shattering of history. But, as music underneath my own effort in Republic Café, Baltics was an inspiration.

The poem that prefaces the sequence is “Room,” which follows a bird that has flown into a house, “Like a shapeless flame, it flew / A dozen times around the room.” The image of the bird opens a wider meditation on the world, which “turns to parts … cunning spheres,” and introduces the question of morality: the speaker’s interlocutor instructs the speaker to “always love the face of sin,” which rather than being something distant or abstract, is fully, locally embodied “here, [in] the lips and eyes and skin.” The end of the poem clarifies the bird and the room as a metaphor for life itself, as, “Inside, the tremor of our life Flew in and in and in.” Can you talk a bit about why you chose this poem to preface the book?

“Room” is a poem I wrote before the Republic Café sequence. I published it in 2012 in Poetry magazine. Even though I was long done with working on “Room,” it still rattled around in my head. Not that I could work on that poem any more, but the scenario, the scene, the impetus of the room, tasked me, I guess you’d say. I see “Room” as a detail of the entirety of Republic Café.

It is the only poem in the book with its own title and, as the book’s preface, “Room” instructs our reading of the sequence that follows it. What are its implications for the rest of the book?

Right. Exactly. Well, for one thing, it’s a stand-alone poem. So that’s why it gets its own title. Etcetera. Too, I’m hoping whoever reads Republic Café will see “Room” as an invitation, an overture. It’s the summons for the rest of the book. “Room” opens the book as a true accounting of my own feelings, while the poem, “Republic Café,” is a dramatization of the events, current and historical, that produced those feelings. I wrote the poem in parts or movements, in various orders, and I tried to arrange these moments into a clear narrative order, so that I wouldn’t have to announce the links between them and could focus entirely on the moments themselves.

Republic Café is essentially a love story set against a backdrop of horror. In a way, all love stories are, in the sense that people fall in love every day while horrible things are happening in the world around them. Implicit in this parallel is a subtext of guilt or shame — how can a person allow oneself to be consumed by happiness and pleasure when there is so much suffering around them?

Isn’t that true? It happens every day. And yet, we do. We do all the time. We’re consumed by the paradox. Ilya Kaminsky writes about this as well in his republic book, Deaf Republic. I haven’t seen anyone write about this point, what I’m about to say, but Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic and Biespiel’s Republic Café appear, to me at least, to be in conversation. Can I say that? He has that wonderful poem at the beginning of Deaf Republic that captures the spirit of your question. It’s called, “We Lived Happily During the War.” He writes—I don’t have the book in front of me—but it goes: “forgive us” for living happily during violence and tragedy. That’s the gist. At the end of Republic Café, the very last couplet goes, “You ask—after all that, why does one fight to love? / Because people want to love.”

Ilya and I haven’t talked about this—we hosted him at Oregon St. University for a reading last month—but I think both of us are channeling Czeslaw Milosz in this regard. Milosz’s poems make the argument that one’s most intimate feeling is always tethered to the world’s most hideous tragedies, including the intimate feeling of love or the intimate feeling of joy or the intimate feeling of remorse. I’m thinking of a poem of Milosz’s like “And the City Stood in Its Brightness,” that ends —

And the city stood in its brightness when years later I returned,

My face covered with a coat though now no one was left

Of those who could have remembered my debts never paid,

My shames not forever, base deeds to be forgiven.

Your book centers this tension by repeatedly projecting the imagery of terrorism (ash, debris, falling buildings) onto the body of the lover. The effect is a kind of collage, an overlaying of one set of images over another. At one point, the public horror collapses fully onto the body of the lover, such that “the soundless ashes, scattered and misbegotten, are the color of our lips.” “[T]here are miles of smoke cooling through your shirt, feeling for your throat,” you write. And later in the same section, which falls almost at the exact center of the book: “We understand this to mean that another city must be burned down.”

Yes. There is a widespread ignorance about the past and a lack of interest in the relevance of history among Americans, don’t you think? You’re a Canadian living in Europe—of course you think this! What I was rediscovering about my own existence in the writing of Republic Café is that history is what we are made of, that in order to be present and mindful inside the most intimate of experiences, like making love, like sharing a meal, like talking as friends, we have to forget so much about time and history. And yet, those very things, time and history, are what make us who we are in those moments. They’re what we’re comprised of. Like the words you quote, they’re the “miles of smoke cooling” inside our clothing, “feeling for your throat.”

The speaker then raises the question of forgiveness: “You say, and the forgiveness?” The tone is ambivalent, but one gets the sense that forgiveness, along with love, is a necessary condition for survival.

Is there a religion in the world that’s not, in some form or another, scaffolded by this concept? Forgiveness?

How else to extract the body of the lover from all that debris?

How else to have lunch?

Fair enough. But how did your understanding of forgiveness — and the role of forgiveness — as well as guilt (or shame) take shape as you were writing this book?

That’s a good question. I’m not sure I was able to solve that for myself in this book. I feel like the book raises the question, but doesn’t resolve it. Or, if it does, then it does so by implication, the threads of which, or the contrails of which, I’m not sure I understand. And yet the question of shame, less so guilt, remains of interest to me.

I have a new book coming out in the fall of 2020, a memoir, called A Place of Exodus. In that book I navigate the issues you’re raising about understanding forgiveness more. Or, at least I’m trying to. It’s a book about the rise and fall, if you will, of my Jewish childhood in Texas, about how I came under the tutelage of the head rabbi of the largest conservative congregation in North America. But after the rabbi kicked me out of the synagogue during a public quarrel, I left Texas and my religious upbringing behind. I became all at once an expatriate Texan and a retired Jew.

That sounds really traumatic! I can see how forgiveness would be a necessary part of your reconciliation with that. But there are different kinds of forgiveness. What kind are you attempting to come to terms with: forgiveness of the self? of others? or both?

Time. Is that possible? I mean, can you forgive Time? Can you even forgive yourself? I suppose the answer is yes. But, can you? I mean, the stain is the stain. Right? I write about this very subject in this new book actually. About the Jewish concept of forgiveness, as depicted in Genesis 32, when Jacob wrestles with the angel before reuniting with his brother Esau at the Jabbok River. The concept goes like this: a Jew, when seeking forgiveness, is obliged to compensate the victim, an eye for an eye with something of commensurate value.

In Jewish law, as I studied it as a young man, what we were taught was, when you ask forgiveness, the victim must forgive. For both, it is an act of turning away from one’s former self and becoming a renewed self. Faith is put in humanity and not God. Faith that people can change.

One of the motifs that recurs throughout the book is the idea of forgetting. “For the sake of forgetting, I write,” you tell us early on. And elsewhere: “When I say forgetting, I mean reconstructing.” “If you ask me what is the shape of the world,” you write at one point, “I would say it’s a spiral, a cone, a wisp of smoke / Spinning on the long axis of remembering and forgetting.” Of course, “Everyone forgets,” you remind us. And yet, “It’s not true that I forget things, the memories are there.” The relationship between remembering and forgetting is clearly one of complex entanglement. It begs the question of what it means to memorialize – to preserve in the public memory as well as personal memory – events like 9/11. Was this something you wanted to work out, somehow, in your poem?

I’m not sure I had very much certainty about any of that. And I’m not sure I arrived at any answers. Poetry comes about through the tactile particulars of experience, and not through generalities. I tried to focus my writing, for as long as possible, on the questions, on dramatizing the questions, on immersing the questions inside of metaphor, as well other questions not unlike what you’re asking: what kind of forgetting? what kind of remembering? what kind of history? what kind of love? what kind of faithfulness or faithlessness? I don’t know that I ever developed a fluency at all regarding the answers to those questions. I was just trying to dramatize my own realization inside the political elements of 9/11 or the bombing of Hiroshima or the calamity of the Holocaust and so on.

My early attempts writing the Republic Café were filled with questions such as: What is forgiveness? What is forgetting? What will come of them? Why do we experience them? Same goes with my last attempts writing the poem: What is forgiveness? What is forgetting? What will come of them? Why do we experience them? The only answer I’ve found, a temporary answer is, we experience these things through mourning, through suffering, and through love.

But it’s the precision of memory that gets lost.

Yes. Memory is inherently imprecise. Memory is ultimately a sacred space, with sacred places, sacred landscapes, and a sacred language.

“The imprecision of it is what is most precise,” as you write.

Precisely. Imprecision makes up the particulars of the inner landscape of memory. It’s the result of paying attention to being alive.

One gets the sense, then, that forgetting is a known constant, an act that one can anticipate — one remembers that one has forgotten — and so forgetting is an act that you must keep reminding yourself of. At one point, you even write a memo to yourself about it:

“Tomorrow I must write: Already I am forgetting the first body to be recovered from the debris.”

And later:

“The clouds arrange to meet in the middle of the sky like lovers,

And then part, so that forgetting about clouds becomes a new

pattern against the dead.

“Now the clouds are a parade of flickering light above the city

Like portraits of the missing.”

What role does forgetting play in the act of remembering, of preserving the past and those whom we, the living, have lost to it?

Forgetting is like breathing. We do it every day. Forgetting is one of our deepest responses to life and death. We can’t do much of anything in life without an ability to forget. We would be paralyzed otherwise. Memory, though, might not be the opposite of forgetting. Memory is our version of events. Our private sequence of events. Poetry is one way—one art—to restore, or invent, or mythologize, or ceremonialize these sequences. To reorder them. To locate the metaphors in them. Or drawn from them. I’m not unaware that this forgetting vs. memory framework can quickly become tautological. But forgetting and remembering are eternally betrothed in our ways of making metaphors about our lives. To transform experience in literary art is about selection. What you select is remembered. What you remainder is forgotten.

You have been compared to Robert Bly, one of the essential poets of the “deep image,” as well as to Wallace Stevens, who had an interesting way of triangulating the objects he observed into a kind of prism through which he could see more clearly the hidden planes of reality — a kind of geometric view at the world.

I’m so happy to hear that. Bly and Stevens are touchstones for me.

What is your relationship to these poets? What have you borrowed from them? Have they influenced the way you relate to the image as a lens through which to view and understand the world?

I could say so much. Bly is a poet of the erotic mind. I love that about his best poems. Silence in the Snowy Fields, his first book, with its Jungian clarities, opened in me a new way to travel in my imagination, one that let me bring sadness and tenderness into my first poems in a way that was based in observation more than feelings. I’m deeply impressed by Bly’s moral intensity. He writes with such a direct and forthright approach to the fullness of real things. He’s like Walt Whitman in that regard, like some English models from the 17th Century—though I suspect Bly would reject those comparisons.

Bly’s translations of Spanish surrealists changed American poetry. The influence of his translations and his curation of translation in his magazine is impossible to measure. Stevens is a different cat altogether. He’s a symbolist, for one thing. By that I mean he’s a poet of mortality and invention. He has a powerful feeling for real life and an urgent need to express the way it gets transformed visually by the imaginary. Stevens writes as if letters and syllables and words are paints, and poems are paintings. Don’t you think? Both Bly and Stevens have something in common with Tranströmer, too. No? They are no people in their poems. Well, Bly adds people in his poems late in his career — in all those ghazals with all those literary and artistic allusions.

The consequence of that aura of solitude is that Bly and Stevens’s poems come across as if they’re spoken by the last person alive talking to no one. Bly’s early poems especially are so snow-covered and snow-whipped. Silence. In. The Snow Fields. As for Stevens? Chris Wiman once said that Stevens will never have a great public readership because they are no people in his poems. The only person, Chris said, if I remember this right, is a snowman. Or a man with a blue guitar. But that’s how these guys saw their experience, Bly and Stevens, that’s the sense through which they approximated existence, through which they exactify the inexact. They do so as individual consciousnesses alert to the movements of life and nature and death, the great themes of literature.

Speaking of lenses, one of the features of your writing that really comes through in this book is its intensely visual and cinematic quality. The sense of movement — of objects in motion — is constant. Clouds are moving; birds are moving; even in the stillest scene, emotions are pushing the perspective forward. Has the visual architecture of cinema influenced the way you construct your approach to writing?

I don’t know that cinema per se has influenced the way I approach writing. I’m sure you’re right. I appreciate that observation. Thank you. I’m going to have to think about that. I do conceive of poems as scenes. I conceive of metaphor as drama. Metaphor, best I can define it or best I can make a definition that works for me, is, using the words of one experience to dramatize another experience. The comparison isn’t the most essential aspect of that definition. The dramatization is. The wearing of masks is. I want my writing, vis a vis metaphor, to amplify. I want to write poems that perform. If I’ve any regular habits of metaphor, it would appear to me that by dramatize I must mean tragedize, to amplify the intersections between calamity and love.

As a long poem, Republic Café has a propulsive force that pushes the reader through it. The poem builds upon itself, gathering force as the weight of experience piles up — in much the way that a good novel does.

It’s the thread for sure. I like your characterization. Thank you. That’s very much how I conceive of the poem too. As a narrative. Narrative is essential to its propulsion. Stan Plumly used to say narrative is indispensable to the lyric poem, and I guess that’s what I mean by saying that narrative, in Republic Café, is the poem’s thread—its wire or fiber or filament, its gossamer, its braid.

The effect is a narrative weight that is cumulative, and whose gravity is deeper than can be summarized by any of its various plot points. Yet there is a clear narrative in this work: it follows a couple over a several-day period before and after 9/11. In a way, it reminds me of Mrs. Dalloway, Woolf’s famous 24-hour novel, or Saul Bellow’s Seize the Day. Why did you want to follow a linear progression for this book? Why choose such a concentrated period of time?

Republic Café is a love poem that takes place in a single room, buoyed by the finiteness and infiniteness of time and history. The progression is my take on the verbal energy in the surfaces of things, in the face and body and heart and spirit of things — and by things I mean people, I mean landscapes, I mean history, I mean memory, I mean experiences, etcetera — and then the progression brings all that into myself and resurrects them within myself. An epigenetics of the imagination.

Implicit in Republic Café’s narrative is an argument. You want the reader to understand something about what it means to love in a time of terror — what is it that you want your reader to take away from this book?

There is an argument, yes, and I hope it’s being made by implication. I don’t know what any reader will experience when they read my poems. I always feel incredibly fortunate when I am made aware of any reader. Grateful for every reader. I hope they take away some delight. That’s a very seventeenth century poetics — delight in disorder — but it suits my ambitions best. I hope, too, a reader will take a sense that the details in Republic Café are dynamic. They want to be transformed, but not into something else merely. I want the details to appear as archetype, which makes the details act not as something universal but as something common, something shared, something mutually realized. In this sense I’m a Whitmanian through and through: “…what I assume you shall assume…”

I want to say too, related: the moment is not enough in any poem. The moment is always an activator of memory, dream, even afterlife. I want the reader to be taken away when reading Republic Café. To travel without being anchored to resolution. I can only offer something to the extent of my own limitations as a poet. I have only these words in the poems to offer. I have only my perceptions, and what’s at the core of those perceptions. That’s what organizes my poems. I don’t know that I have much control over that. But it’s through my limitations I offer a reader a way to discover and to recognize existence. I guess I mean: I’m merely the maker of the poems, and my role is to recognize and to discover something afresh about existence, best I can.

So, I guess I’m asking a reader to take away something that is essential to my nature as I relate to the world. I’m asking a reader to accept my poems on those terms. As Frost says in “The Pasture”: “I shan’t be gone long.—You come too.”

— Interview by Joshua Mensch

_______________________________________________________________________

Read more by David Biespiel:

Poem in The New Yorker

Poems in Poetry

Poems at The Academy of American Poets

Essays in The Rumpus

More interviews with David Biespiel