SEX AND THE HOLOCAUST

I’ve been masturbating for as long as I can remember. Sometimes it seems that I came out of the womb with my hands on my penis. I started early and was, from day one, an avid practitioner. At the beginning, my technique was primitive. I would massage my penis with my thighs until my entire body was overtaken by a sensation I can only compare to a flash of light that illuminated me from within, briefly but with Klieg-like intensity, and left me gasping, limp and serene. It was that overwhelming climactic moment I was after, my dry ecstasy, again and again, and the tranquility that it brought in its wake.

How did I learn to jerk off? Was it a chance discovery while I was trying out my brand-new body, or are we all hardwired for self-stimulation and the pleasure it brings? I tend to believe we are natural-born pleasure seekers, in couples, groups or solo, in food, alcohol and weather, even in work. As Freud put it, in Civilization and Its Discontents, “The goal towards which the pleasure principle impels us – of becoming happy – is not attainable: yet we may not – nay, cannot – give up the efforts to come nearer to realization of it by some means or other” [emphasis mine].

Masturbating is pleasure principle’s most convenient medium, mere child’s play. And, after all, apes and monkeys masturbate, as do dolphins, whales and elephants, bats, lizards and walruses. To name just a few. Still, there was something unusual, if not downright freakish, about my onanistic compulsion when I was an infant. I did it whenever I was alone and lying down, any time of day or night. I couldn’t help it.

The question is why. I’ve come to believe that my obsessive autoeroticism was an instinctive response to stress and/or fear, and that the cause of the stress and/or fear to which I was so energetically reacting was the stress and/or fear my parents felt living in Germany after the war. They were Polish Jews who’d survived the Holocaust, had seen parents, spouses, siblings and offspring taken away to be murdered, had been abused daily, had survived brutal conditions amidst the constant threat of death, had seen the corpses, had witnessed many killings, most of this horror committed or ordered by Germans.

And we were living in Germany, just a few years after the war, among people who may have been part of the terror, who may still have harbored the racist hatred that led to the gas chambers. My parents could not have felt comfortable or secure during the 12 years they lived in the country after their liberation. It’s possible that I felt their dread and their history through my physical contact with them, perhaps as early as at my mother’s breast, that I felt the terror in the rhythm of their heartbeats, the pace of their breathing, the sound of their voices, the tension in their bodies.

But there might be another, more profound reason: epigenesis or, in its contemporary definition, a change in genetic expression of children as a result of the traumas their parents had experienced. In an interview published by Project for Media in the Public Interest, Eva Jablonka, professor of epigenetics at Tel Aviv University, explained that children inherit “epigenetic marks” from their parents that are carried in the eggs and sperm.

“Epigenetic input depends on what happened to our parents, what genes were active in our parents,” she said. “And the genes that were active depends on their own experiences, on their lives, on what they went through.” In other words, parents pass on to their children the consequences of their interaction with the world, especially when those interactions were traumatic or stressful.

Not long ago, I came across a story on the Internet reporting that researchers at Mount Sinai Hospital had found indications that the trauma suffered by survivors of the Holocaust can be passed on to their children. I read the article with great interest, of course, because here was a level of being fucked by history I hadn’t considered or believed possible (because I’d learned at school that it wasn’t possible). Though it made sense, of course. If the mind is a part of the body, the body is also present in the mind, and traumatic events that engage the deepest stratum of the psyche could leave indelible impressions on the body’s most profound component.

In the study, carried out by researchers at Mt. Sinai Hospital, 32 Jewish men and women who had either been interned in a Nazi concentration camp, witnessed or experienced torture or had hidden during the Second World War, were examined, as were 22 of their children. The researchers wrote of their results: “This is the first demonstration of an association of pre-conception parental trauma with epigenetic alterations that is evident in both exposed parent and offspring, providing potential insight into how severe psychophysiological trauma can have intergenerational effects.”

More specifically, what the Mt. Sinai team calls “Holocaust exposure” had an effect on genetic processes in both parents and their offspring that was described as “significantly correlated” and observed in a site on the gene “associated with parental trauma.” In other words, the child “feels” his parents’ pain.

“In summary,” the researchers wrote, “our data support an intergenerational epigenetic priming of the physiological response to stress in offspring of highly traumatized individuals. These changes may contribute to the increased risk for psychopathology in the F1 generation.”

F1, c’est moi.

And so, with the Holocaust deeply entrenched in my genes, I masturbated every chance I got. I was 10 when I first detected a wet smear on the front of my pajama bottoms after masturbating. I first thought I’d pissed myself. Then, slowly, it dawned on me. Aha. Oh. Okay. But this new element presented a logistical problem: I now had to hide the evidence of my erotic hobby. Toilet paper, obviously. A big wad to catch my small wad. Eventually, Kleenex tissues proved more practical and the load could always be passed off as something else, a spill, a crushed bug, snot.

I had to hide the evidence because my parents beat me whenever they caught me at it. They were against it, violently. Especially my father. He’d grown up in a very large family – he was the eldest of 11 children – who’d lived together in flat in Łódź, and then in a much smaller apartment in the ghetto of that city. I assume that all the children dressed, undressed and slept in the same room. It’s not difficult to imagine the potential for incestuous fantasies and longings. So, there must have been a strict and harshly enforced taboo against anything erotic. There must have been beatings for any transgression. My paternal grandfather, as my father told me, was a big man with a fierce temper who never spared the rod. As the eldest child, it’s possible my father inherited the role as enforcer of the taboo, and he went to great lengths to do it.

Once, when I was about four, after the standard good night kiss, he turned off the lights, as usual, and then I heard the bedroom door close, as usual. I started right in, no hesitation, no warming up in the bullpen. Within seconds, the lights went on and my father loomed above me, a grin of sadistic glee on his face. He hadn’t left the room; he’d simply pretended to, by shutting the door from inside the room. The beating that followed – on my buttocks, as usual – was a little more severe than usual. But it didn’t stop me. I merely became a bit more circumspect, a little more paranoid, holding my breath to better hear a foreign presence in the dark, waiting until my eyes became accustomed to the dark, just in case he thought he could fool me twice.

I once asked my father why I wasn’t allowed to play with myself. He replied,

“Because I say so.” The four words that define tyranny: Because I say so.

“Patriarchal laws pertaining to culture, religion and marriage are essentially laws against sex,” that brilliant madman Wilhelm Reich writes in The Mass Psychology of Fascism. I believe this, absolutely.

“The sexual act, successfully performed,” George Orwell has George Smith reflecting in 1984, “was rebellion. Desire was thoughtcrime.” And, elsewhere in the book: “The aim of the Party was not merely to prevent men and women from forming loyalties which it might not be able to control. Its real, undeclared purpose was to remove all pleasure from the sexual act. Not love so much but eroticism was the enemy.”

This was the first battle my parents and I fought, and it became the engine for all my future resistance against them, which lasted until both had died. Eros versus repression. Gratification versus tyranny. My pleasure versus their authority. Because I rebelled against my parents’ vigorous attempts to suppress my quest for pleasure, I eventually rebelled against anything they asked of me that I found unpleasurable. And what I found most unpleasurable was their demand that I devote my life to compensating them for their suffering in the Holocaust. The German word for reparations is Wiedergutmachung, literally ‘to make good again’. They wanted me to make it all good again by becoming a rich and successful, a son to boast of and display, a son that justified and gave meaning to their survival.

“We come to America for you,” my father explained. “So you can be a big success and make us happy. We come to America for you. So you owe us this.”

But I didn’t want to do that. I didn’t know why I didn’t want to do it, but everything in me rebelled against it.

“Your parents suffer so much,” my aunt told me. “You are smart. You have to study and make them feel good. This is all they want. You owe it to them.”

So, not only was I born with a trauma, but I was also born indebted. I nodded, poker-faced, and kept silent.

It’s possible that without this obligation they imposed on me, this debt, I might have gone after success and affluence on my own. But I didn’t want to give it to them, I didn’t want to do it for them, for their Holocaust. I wanted the polar opposite of the Holocaust, the antidote to blood and ashes, loss and suffering: love and pleasure. I wanted to live my life, not theirs.

I can see that now. But at the time, when I was an immature adolescent, all I knew was No, not that! Anything but that!

In my parents’ vision, I was to become a lawyer or a doctor or a banker, or even, as a last resort, a college professor, something professional with standing and an excellent salary. But, as my father never tired of telling me, and which I certainly knew, I was a great disappointment.

Here is a partial list of the jobs I worked at during their lifetimes (in the order of how they tumble into my memory):

– dishwasher

– short-order cook

– pizza cook

– bartender

– grocery store clerk

– fabric sample cutter

– construction gofer

– store detective

– caddy

– bookshop flunky

– sawmill flunky

– telephone salesman in an illegal scheme, run by Hungarian racketeers, to sell office supplies to businesses and schools by pretending to be a high school teacher who had run a small stationery store to supplement his income but was now liquidating his entire inventory, at cut-rate prices, because he had taken a job with UNESCO in Lagos, Nigeria

– bicycle messenger

– taxi driver

Not long after my mother died, I was hired as an editor at Sterling Publishing. Less than two years after my father died, when I was 46, I became a professional journalist. Coincidence? Hardly. My ignoble curriculum vitae was largely the result of my refusal to engage in any activity that smacked of concession or Wiedergutmachung. That may be a classic example of cutting off your nose to spite the face – but I couldn’t help it. My resistance wasn’t planned or in any way voluntary. I was not, and never have been, the Che Guevara of infantile rebellion. I was simply a toddler with a grudge, who grew into a grudge-bearing adult. And to some extent, because they wouldn’t let me jerk off in peace.

In all other aspects of my life as a child and adolescent, I was obedient and polite, passive, industrious and meek. I tried to be a good son, and was. Until university, I did well at school, kept my room and nose clean, never whistled at the table, went to synagogue on the High Holy Days, went to Hebrew school, kissed ass, gave them cards for their birthdays as well as on Father’s Day and Mother’s Day, smiled in the presence of adults, never jerked off in public.

But I did continue to masturbate, even more prolifically than before. Because America was a jerk-off paradise. Playboy. Marilyn Monroe and Jayne Mansfield. Girls that wore skirts ending at the kneecap. Push-up bras. The Maybelline TV ads (which showed matching bras and panties, with the model discreetly airbrushed out, slowly revolving, as in a dream). The movies, tumescent with suggestive sex and populated by beautiful, seductive and scantily dressed women.

In Germany I’d had very little to inspire my erotic fantasy life but the sounds of my parents having sex. America gave me a world of erotic images: the lips of the young woman smoking a Chesterfield, the hips of the model leaning against a Chevy Bel Air Impala, the breasts of Anita Ekberg in “Sheba and the Gladiator” – all of it fuel for my fire.

But, socially, I was messed-up. There is a photograph of me, taken by my mother on my first day at junior high school, when I was almost 13 years old. It shows a short, pudgy, unhappy adolescent with hunched shoulders, a rounded back and a ridiculous haircut, wearing a white shirt, white socks and an expression of pained embarrassment. I carried that sad, anguished boy around for years, and I think his image haunts me still.

What was the matter with me? Well, first, I was an immigrant and outsider, just as I’d been as a Jew and an outsider in Germany. Though no one ever said anything or acted in any way to suggest that I was different, it was a constant embarrassment because I knew I was. I felt different. I identified with the chubby Bulgarian boy I knew from elementary school, who collected empties every Sunday in summer at Orchard Beach to bring home for the deposit that would be repaid on them. He was fat, perpetually sunburned and ill at ease, so clearly ashamed of being who he was, a poor immigrant in glittering America, where normal people were beautiful, owned color TVs and new Chevies and didn’t need the nickels from bottle deposits.

And, then, I felt guilty because I was a bad son. I knew I was a bad son because my father always told me so and because of what I did and thought in secret. I masturbated and thought almost constantly about girls. And I had very ambivalent feelings about my parents. Sometimes I loved them and sometimes I hated them. And sometimes I felt nothing at all. In Germany, adults had often asked me, “Do you love your parents?” It was, in their minds, a question with only one answer. So I always gave them what they wanted to hear. But I didn’t know what I felt, I didn’t know if it was true that I loved them.

Still, though I was painfully shy, I tried to be normal. I went to dances, clumsily gyrated to rock music, always a whisper behind the beat, and tried to learn how to talk to girls without revealing what was on my mind. Because my father was brutal and severe, I had to look elsewhere for a model of manhood. I found it in the movies. The ideal man, as I construed him from the films I saw, was an assemblage of Bogart, Burt Lancaster and Paladin, the gun for hire played by Richard Boone in “Have Gun, Will Travel,” a ruthless cynic dressed in black. These were all men who seemed to play by their own rules and were indifferent to what others thought of them. Unfortunately, I had no rules of my own, and I lacked the self-assurance to play by Bogie’s.

The seminal social event of my early teenage years was Nicky Bloom’s birthday party. I was 13 years old, and Nicky was my best friend, if only because he lived across the street from me in the Bronx. His father had died when he was young, and his mother was bitter, domineering and clearly out of her depth as a single parent. Growing up fatherless, as Nicky had since the age of six, made him feel underprivileged, and he was ashamed of it the way kids are ashamed of being poor. He never talked about his father, and refused when asked. He was as socially inept as I was, yet he had the bold, slightly lunatic idea of inviting the three most popular girls in our class to his birthday party. And for the other side of the gender divide, he invited me and Jimmy Drano. Nicky, Jimmy, me – the three biggest twerps in the class.

Our partners were to be Ronny Lynn Spindel, a beautiful Jewish American Princess with long honey-colored hair and slim, elegant legs she never hesitated to display, weather permitting; Lynn’s best friend, Ellen Weinberg, statuesque, straight-backed, with short dyed blonde hair and the daunting manner of a Mafia don; and, finally, Gail Solomon, blonde and sophisticated but very thin, bespectacled and generally ill at ease, her social status deriving primarily from her being Lynn’s second-best friend.

I wonder, now, why they had accepted the invitation. Were they as self-assured as they appeared to be? Was it just for a lark, something to laugh about later? Did they get a kick out of being admired by the likes of us? Or were they genuinely kind? I could see that in Gail, because she was not very self-assured. But Lynn? Never. For a long time, I did not believe that beautiful women were capable of kindness – because they didn’t need to be kind to be admired. In those days in America, and especially among teenagers, beauty was a kind of wealth, a natural resource that you did not spend on a whim.

When I heard that they’d accepted the invitation, I was terrified. I was sure it would be a disaster. Nicky was an unattractive boy, with a pasty, yellowish complexion and hair the color of wet rust, which he wore in a ragged crewcut. He wore boxy black-frame glasses and stuttered in the presence of girls. Jimmy was a tall, ungainly boy with an aw-shucks manner, a large wart on his left cheek and a protruding Adam’s apple that bobbed and weaved when he spoke or swallowed. And then there was me, pudgy, pale, timid, badly dressed and with the social savoir-faire of someone suffering from a fatal disease.

I still remember the six of us heading for Nicky’s place that Saturday afternoon, after we’d met the girls at the bus stop on Tremont Avenue. We walked through a greasy drizzle, the girls dressed in their party clothes, their hair Teflon-perfect (Lynn’s had a blue ribbon in it), the three of us shielding them from the raindrops with umbrellas.

Nicky played music on his record player. I remember now that the pretext for the get-together, besides his birthday, was that the girls would teach us to dance properly. We danced. We tried to. The girls were patient. Jimmy turned out to be a natural dancer. Dancing with Lynn was thrilling. Her skin was soft and warm, which surprised me, since I’d expected her to be cool as marble. Her body smelled of Ivory soap and something else, a subterranean perfume, faintly pungent, almost like the scent of blood.

“Not bad,” she told me, after our first dance.

I thought so too.

Nicky’s mother brought the usual refreshments, potato chips, cupcakes, Coke and a chocolate cake with 13 candles. But she did not miss the opportunity to criticize Nicky for getting crumbs on his shirt. We ignored her. She flitted in and out, like a nervous maid, until Nick ordered her to stay away. Because there would be kissing lessons.

Ellen was my instructor. “You’re doing it wrong,” she told me.

“Sorry. Let’s try it again.”

I tried to remember how the boys of the Silver Screen did it. Purse the lips. Open them? How wide? Ellen was demanding. She said I’d improved with practice but still didn’t quite have the hang of it.

Of course, Nicky – the birthday boy – was put in Lynn’s hands. His problem was that he turned bright red and got the hiccups. Gail informed everyone that Jimmy was an excellent kisser. There was a round of applause. Jimmy took a bow.

After the party, and after we’d accompanied the girls to the bus stop, Nicky, Jimmy and I were smug as studs. We’d survived a test of sorts, overcome our own shadows for a few hours.

At home, I lay in bed and remembered the feel and smell of Ronnie Lynn Spindel, the soft heat of her when she leaned against me as we danced to Elvis’s “Are you Lonesome Tonight?”, the press of her padded bra against my breast, the down on the back of her long neck, the secret scent of her body.

I reached for a Kleenex.

_______________________________________________________________________

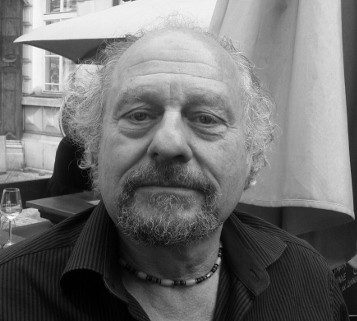

SIEGFRIED MORTKOWITZ works as a free-lance journalist and lives in Prague. His work has appeared in B O D Y, Brown’s Window, The Prague Revue, and After Hours. His first chapbook, Eating Brains and Other Poems, was published by After Hours Press in 2014.

_______________________________________________________________________

Read more by Siegfried Mortkowitz in B O D Y:

THE STORY: Siegfried Mortkowitz on Leonard Michaels’ “City Boy”

Poem in the May, 2013, issue

Poem in the September, 2012, issue

THE POEM: Reading Frank O’Hara’s “The Day Lady Died”

Poem in the January, 2018, issue