Prose Poetry and the City

by Donna Stonecipher

Parlor Press, 2017

182 pages

Reviewed by Kate Singer

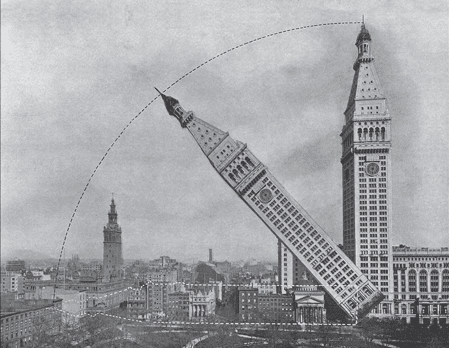

I once asked Donna Stonecipher if she, formidable prose poet that she is, ever felt a nostalgia for the line. I surely wouldn’t have asked that question had I already read her Prose Poetry and the City, a probing, flâneur-like meander through the history and poetics of the prose poem. Stonecipher’s history is written not unlike the prose poem itself—an open space of relations that view modernity and its poetics not as a matrix, a network, or a panopticon, but rather as a series of moving tensions. She builds the space of the prose poem by perusing Paris’s nineteenth-century urban landscape that gave the hybrid genre birth. We start oriented in language as it takes root in the city’s ways and means, especially the tension between, on the one hand, the “vertical” city conceptually rendered through maps and understood through a bird’s eye view of patriarchal control and architectural planning and, on the other, the “horizontal” city of lived experience. The conceptual city, with its godlike vertical first-person perspective, structures not only the monologic lyric but the formal control of meter and rhyme. Yet, it is the latter where Baudelaire’s flâneur roams, making acquaintance will all sorts of people and dives by way of a dialogic, prosey sentence.

Such a crux shapes several interlocking discoveries about a genre that has come to be so all-pervasive and yet still so mysterious in our own poetic landscape. It allows her to explain why nineteenth-century poetry fractured the formal bounds of form and meter in strikingly different ways in America and France. Whitman developed free verse just before the vertical power of skyscrapers came to dominate the New York state of mind and authorized the bold, individual excesses of his long line that remained married to the strictures of the iamb. The more grounded prose poem, by contrast, labored through Paris’s more sedate horizon. In Baudelaire’s sentence, Stonecipher finds an equilibrium between the capitalistic individual and the crowd, the vertical sublime and a more uniformly horizontal city, the formal commands and limitations of meter’s imposed hierarchy and the lackadaisical habits and heartbeats of breathy clauses, attached one to the other indeterminately or contingently.

If the prose poem leads out of the supposedly monologic lyrical voice of solitary Romanticism, as Valery and Rimbaud would have us believe, it does so by exploring the novelistic dialogism that was the boon of capitalist fictions from the eighteenth-century onwards. Here we see again the capaciousness of the prose poem, and not only for its polyvocal polyphonies of place and person. In part, born out of the desire to make money, Baudelaire capitalized on the lucrative success of the novel and other popular prose forms by publishing his first set of prose poems in the newspaper La Press. The prose poem adopts the garrulous variety of the novel, not to mention the legal, journalistic, and other urban discourses of modern prose, and tempers it with metaphor. This hybrid genre has always been associated with freedom, openness, subversion, and social critique. However, as Stonecipher shows us, it does not simply throw off the suffocations of the tight alexandrine or the teleological concepts of symbol and form (e.g., the courtly blazon and the sonnet); rather, it incorporates the conceptual, paradigmatic transformations of metaphor amid the urban sprawl of utilitarian prose.

Thus, the dynamism of the prose poem works reversibly, in both ways, integrating the discursive and lyrical, or more specifically the metonymic and metaphorical. In perhaps one of the most fascinating discussions of the form’s texture, Stonecipher counterposes the filled-in space of the text-dense prose poem with its tendency to inaugurate breaks, gaps, and ruptures within that crowded (urban) space and the sentence’s usual hypotaxis not via the exterior control of line breaks but through a variety of parataxis, asyndeton, juxtaposition, jump cuts, association and other “leaps and gaps.”

For readers who think, as I did, of a prose poem as a block of prose amped up by metaphor and lyrical language, Stonecipher shows how a prose poem’s sentences create unexpected spaces, or gaps, within their own continuous (and urban) flow, gaps that can be even more numerous than lineated poetry’s caesuras and line breaks.frequen Think of a neighborhood amble that is, of course, continuous yet consciously represented by a series of landmarks, remarked-upon items in shop windows, the Michael Jackson impersonator sauntering by, a clownish Frenchie licking the pavement, and other O’Hara-esque effluvia. Stonecipher cites Rosmarie Waldrop’s tricksy use of conjunctions, where “and,” “but,” “though” bring the expectation of hypotactic logical connection (“I like poetry but also prose poetry”) yet enact asyndeton that cuts out logical connection (“I like poetry but it is gloomy in LA in June”), creating what Stonecipher coins as “hypertaxis.” Here we have all the crowded arbitrary richness of the city’s fortuity that holds its own jangly, frequent serendipity.

A reader might crave a bit more context, possibly a longer historical sense of the urban or a view to British or other global prosey contexts, or perhaps a consideration of the “dissents” to her argument throughout the book rather than placed in a short section toward the end. But this focus serves the lilt of the book: there is something wonderfully prose-poemish about its writing, which seems to create a critical, investigative prose form all its own. Interfusing academic studies with contemporary and current poet musings about the form, Stonecipher writes something both lyrical and discursive, critical and imaginative. Perhaps taking her cue from the very form she is so adept an architect of, the twenty-four short sections muse on the space and architecture of the late nineteenth-century city even as they weave through the spaces of the prose sentence, the page, and the commodity culture that encircles and yet is escaped, at least in moments, by both. Take this in your bag as you traipse through any city this summer, and your mind will surely follow into unexpected pleasures.

— Kate Singer

_______________________________________________________________________

KATE SINGER is Associate Professor of English and Chair of Critical Social Thought at Mount Holyoke College. Her work has been published in Studies in Romanticism, European Romantic Review, The Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy, and Literature Compass. She edits the Pedagogies section of Romantic Circles. Her monograph Romantic Vacancy: Gender, Affect, and Radical Speculation is forthcoming from SUNY this summer.

_______________________________________________________________________