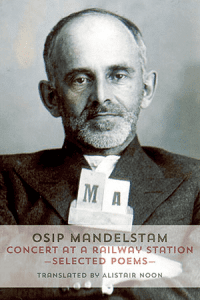

Concert at a Railway Station:

Concert at a Railway Station:

Selected Poems

By Osip Mandelstam

Translated by Alistair Noon

Shearsman Books

142 pages

Born in 1891, Osip Mandelstam is a contemporary Russian poet. His poems were indeed published during his lifetime and he was appreciated and read by contemporaries, but after his death in 1938 he was banned by Soviet censorship and remained essentially inaccessible to most readers in Russia.

After Stalin’s death, Mandelstam was gradually reintroduced to the Soviet reading public, but it was only in the 1970s and 1980s that his oeuvre was published in its entirety. Even today the conversation about Mandelstam and his work continues to develop. Alistair Noon’s translations of Mandelstam are an important contribution to the study and appreciation of this vital writer.

Mandelstam was a difficult, intellectual poet. He put the joy and pain of western culture, its beauty, mythology, and spirituality, into filigreed verse forms in which the rhyming of allusions, quotes and ideas is echoed by the rhymes of words. Translators of Mandelstam tread on thin ice: any false step creates cracks. Noon’s method for avoiding this is to preserve the formal features of the poems rather than finding the exact corresponding expression. This does not mean that Noon’s translations are not precise. On the contrary, they are very precise, but in their own specific way. In most cases, Noon preserves the rhyme and the rhythm of the originals, but he himself is a poet, and often it seems that his own poetic sensibility stands behind certain choices. A translator is always an active interpreter of the poet translated.

Noon’s emphasis on formal features allows him to reveal meanings that might not appear obvious at first sight. For example, the poem “Tristia,” which is the central piece in Mandelstam’s second poetry collection of the same name, begins with the statement “I’ve studied the science of separation” in Noon’s rendition. Here the word “separation” stands in for the Russian deverbal noun “rasstavanie.” One may argue that its literal translation would be parting, leaving, or going away; the word has an aspect of intimacy, romance, closeness, and melancholy. Noon’s choice reflects this, yet “separation” is a more intellectual concept that presupposes a poet-observer who divides the world into contemplated parts and studies them as if he were indeed a scientist.

Apart from the advantage of sibilance, Noon’s choice here also brings out the central leitmotif of Mandelstam’s life and poetry: his life-long history of breaking up with things, ideas, people and places, which sometimes happened against his will. From that perspective, the poem also shows how radically Mandelstam’s poetics had changed in his second collection. As the philologist Mikhail Gasparov pointed out, in Tristia “the texture of the imagery that constitutes the fabric of Mandelstam’s verse had become immensely more complex” than in his first collection, Stone.

This complexity is described by a contemporary of Mandelstam, the symbolist poet Valery Bryusov, as the “poetry of paradox.” Elaborating on this, Bryusov wrote “every word [in Mandelstam’s poetry] is a bundle of meanings that stick out in different directions and never head towards one official point.” The word “bundle” is particularly important in discussing Mandelstam. The smallest unit of meaning in Mandelstam’s poems is not a word, but a combination or group of several words. These groups may sometimes appear paradoxical, but their overall semantic construction is always a precise poetic statement. A good example of this method is the following untitled love poem from 1925, as translated by Noon:

Through the gypsy camp of the darkened street, I’ll rush

After a cherry branch bouncing away in a carriage,

Its bonnet of snow and endless din like a millstone.

In this stanza the metaphors are not really metaphors, as one thing is not conveyed through another. Rather, two images are combined to enhance and supplement each other. Take one word away and the construction will fall apart. “Gypsy camp” is Noon’s rendition of the word “tabor,” which in Russian is most frequently used to denote a gypsy settlement, although it is not limited to that. But what is important is that by using this word Mandelstam imbues the image of “the darkened street” with a feeling of claustrophobia, a lack of personal space. Adding the adjective “gypsy” to the word, Noon not only amplifies this initial meaning, but also foregrounds the ideas of motion and unpredictability that are inherent in the image of a camp. This is also natural to the process of moving down the street. The sense of movement continues at a different level:

All I recall’s how the chestnut locks misfired

And their smoky bitterness – better to say, ant acid.

Their amber dryness lingers here on my lips.

Here the semantics of the poetic statement are broken into smaller pieces that only make sense when combined into a whole. It is hard to say precisely what the pun “ant acid” actually means, but the image evokes a sense of bitterness, and since ants are often black there is also a visual aspect that echoes with “the darkened street.” Clinging to one another, these pieces create a unity that conveys a feeling of love and slight confusion, a kind of synaesthetic vision where senses are intermingled and color has the quality of smell and vice versa.

On the other hand, sometimes Mandelstam’s complexity of expression is determined by the intricacies of Russian morphology. For example, in one of his most famous poems, about the rise of Stalinism, there is the word “pol-razgovortsa,” which is a diminutive of “pol-razgovora,” which literally means “half of a conversation.” It is a problematic word to translate. The diminutive suffix “tsa” in combination with the prefix “pol” creates a sense of doubled diminishment which, with the political context of the poem in mind, makes the word sound ominous and despicable. How to convey this in English? Noon elegantly solves the problem by extending the metaphor:

We live, but feel no land at our feet,

nor ten steps off any whisper of speech.

Where half a conversation finds enough lips,

it’s the Kremlin-Climber our thoughts are with.

The image of a conversation that cannot happen because there are not enough lips to have it seems to be totally in tune with Mandelstam’s original intention. This metaphor renders the crucial idea of speech disconnected from the speaking subject. Noon’s choice of expression sounds authentic: it reflects the suffocating atmosphere of the 1930s that Mandelstam captured. The rest of the poem also preserves Mandelstam’s poetic intuition, and here again Noon’s choices bring out some unexpected meanings.

For instance, the euphemism for Stalin, “Kremlin-Climber,” is an alliterated rendition of the word “Goretc” used in the original. It means a person living in the mountains, especially someone from the Caucasus. Whereas Noon’s translation loses this allusion to Stalin’s place of birth, it highlights the political career of the tyrant who, by way of intrigue and deceit, managed to climb to the top.

In his essay “Fourth Prose,” Mandelstam wrote that all world literature can be divided into books written about resolved themes and those that have no resolution. The latter he called “stolen air.” Mandelstam’s own poems are a kind of stolen air. It is air that is electrified with the meanings of world culture perceived through the lens of his own intense and tragic life. Alistair Noon’s selected translations of Mandelstam’s poems illustrate this life-long activity.

Starting with Mandelstam’s first book Stone and ending with his late uncollected poems, Noon’s translations preserve the icy perfection of Mandelstam’s rhymes and rhythmic patterns. In so doing, Noon’s own poetic voice can be heard, which is appropriate in translations of Mandelstam’s poetry, as Mandelstam himself propagated an idea of creative, interpretative translation. Mandelstam’s poetry was, among other things, a result of his vigorous commitment to art and world literature. His poems were attempts to render his encounters with culture into language, and it is only by subjective interpretation of these experiences that he can be translated into other languages.

–Anton Romanenko

_____________________________________________________________________

ANTON ROMANENKO is a student of English and American studies, and Russian literature at Charles University in Prague.