GERMANS

There are eleven of them. Why I remember the exact number is uncertain, perhaps because it’s enough to field a football team. They arrive by train, a short sixty-mile ride west from Washington, D. C. to Winchester, Virginia, an old Civil War town that has the distinction of having been exchanged, North and South, more than seventy times, 1861-1865. They’re dressed in army prison khaki green, black boots, and are marched like soldiers — which they are — right through the center of town, right from the station past the Frederick County Courthouse and the Great Red Wooden Apple on its front lawn, past the Greco-Roman-inspired architecture of the Public Library, and on out to the P. W. Plumly Lumber Corporation sawmill. To say they march is probably an exaggeration of their very formal walking, whose stride is nevertheless very military. It’s a parade, maybe 9:00 or so in the morning, May, as I remember, 1944, my father, with his holstered .22 pistol, at the head of the local National Guard that is escorting them to the Quonset hut quarters my grandfather has had specially built for them.

In spite of the hour, there are lots of spectators along the sidelines, mostly mothers and small children, plus a few townie dignitaries, even Senator Harry Byrd (who has sponsored their arrival) and P. W. and some employees, though, now that I think about it, they’re all likely waiting for the Germans at the other end. It’s rained earlier, so the red brick streets are slick and the procession slower than it might be. That way you really get to look at them, enemy and alien, a whiter race, having arrived, as if from outer space, from a far-off foreign war. I’m still not in school since there’s no kindergarten; I have plenty of time and freedom to take things in, whether or not I understand them.

My father has complained for some time that he’s shorthanded for the out-in-the-field jobs, a consequence, by now, of nearly three years of American participation in the war. Lumberjacking, even in the relatively new-growth parts of the Shenandoah, is tough, young work. The Shenandoah is protected property, state and federal, but in these war years you can lease heavily forested areas for selective harvest. My grandfather also owns farmland just at the edge of the city, which he turns into apple orchards. So on the one hand, he’s in the business of bringing down trees — big hardwoods — and, on the other, planting trees for cultivation. (The economy for him, and for many American businessmen, is the war; and still will be well after the war.) My grandfather, in the best sense, then, is a farmer of trees. In good weather, as I remember, we camp out in the Blue Ridge for two or more days at a time, though I usually don’t last the third night. It’s the cold more than anything, the thick damp cold that settles in from the thickness of the leaves. It falls like breaths of rain.

The few men my father normally works with are all older: poor, white, heavy smokers, with drawn, mask-like faces, and bodies that seem, from forever, bone-tired. They’re leftovers — men too old or out of sorts to volunteer or get drafted. My young father is the straw-boss. The Germans are here to fill out the work force. They don’t seem to mind their mission, which is essentially forced labor: for them it’s a kind of freedom — from the war, from prison, from soldiering, from fighting, from death, and from filth, poor food, and, what I would imagine to be if I were older, the noises of death and death’s silences.

It turns out that as the war in Europe seems to be either building or winding down or simply exhausting itself — though who can tell with the ongoing prevalence of those button-size red coupons and white lard-like butter substitutes and rag-and-paper drives and endless ads for war bonds — it turns out that we have as many as five hundred Internment Camps here in America, mostly populated by Germans. These camps are everywhere, including farm country as well as just outside major cities. The 1929 Geneva Convention stipulates that war captives must be “housed safely and fed well” — a “Geneva holiday” it’s called. There are enough POWs nationwide to make a fair-sized international city: 371,000 Germans, 51,000 Italians, and 5,500 Japanese. Occasionally prisoners are “released” out into the community to fill in for the absent military-age population, which is how my grandfather secures his eleven Germans. Virginia’s senior senator Byrd is a friend, and as a gesture of thanks for my grandfather’s financial support against Roosevelt and the Democrats, as well as his war contribution (for one, the manufacture of Piper-craft airplane propellers), Byrd manages to requisition these prisoner soldier-officers for whatever work my grandfather’s lumber business needs doing — from labor at the sawmill to planting apple trees to, more importantly, cutting down hardwoods. The Germans are already in Virginia, in a camp outside Washington.

Lumber camp will be a camp of an altogether other kind. Mostly, I think, it has to do with focus and clarity. It’s all and only about the trees and the men — ten, twelve hours a day over, say, a three-day period, usually middle of the week. Other than the work, it’s like camping out, at least for me it is, whenever my father lets me tag along. I won’t be in school until I’m six and the war is over, so for me it’s an experience well beyond the task at hand. It’s an other-planetary German experience.

Though it’s the big trees that matter most. From my five-year-old perspective, looking up through an oak’s muscular branching, the older regular loggers are, too much of the time, men who seem diminished next to what they are trying to bring down. For me the largest of the trees loom like — what? — gods, though that’s a concept I have no idea of, only an impression of something wholly surpassing, like pictures of great animals in books: mystical oaks and spread-out, big-leaved maples and shagbark hickories among the most prized. On clear days, summer and fall, the broken sunlight falling through the oak and maple and hickory branches make for a deeper, higher stillness, and an even greater stillness if you can stand alone next to one and look straight up through the pieces of the green and blue canopy. It turns you around, just standing there, with your head back, so that you have to lean against the tree’s rough body in order to keep your balance. Trees, by themselves, are grand enough, but in vast numbers on the side of a mountain they take on a wild, other life. But it seems to me, in this moment, I’m the only one who thinks so. This is business and the task is too difficult to think much at all. The Germans, unlike the men my father has generally had to work with, seem to be a natural fit for the scale and labor of the trees, if only because they’re happy to be anywhere outside the stockade.

The Germans seem, to a child, to be as strong and stubborn as the trees — lean, straight, hard as the wood just under the bark. Then again, their blondish heads look square to me, as if their minds have corners. Out on the job in the Shenandoah, the Germans pay me no attention, which is easy all around, since my own job is to be sort of gone, to hang at the near peripheries. I am, therefore, neither seen nor heard, except when I’m not. It’s not natural to be completely quiet, though quiet is how you hear what’s really going on — nature, Germans, or otherwise. I guess I spend as much time watching the birds and squirrels and the occasional surprised deer as I do witnessing the work. The songbirds and the crows chatter and caw throughout the day and fly in and out of the shadows as if on business, which, I suppose, they are on. The squirrels sort of chatter too and zip electric from place to place as if wired — in a few years I’ll try to shoot them with small-bore bullets and never hit one.

There are probably black bears, but there are too many of us for the curious. This may not be the wild, exactly, the distant strange world you see in books and at the movies, but it’s natural, right along the edges of where people live. And there are ruins, natural ruins, fallen dead trees and parts of trees all mixed up together, limbs crossed over, trunks rotted and split open, root and branch in pieces. The universally-gray tree parts just lie there, like ghosts of themselves, between here and the invisible. Most of the parts will in no time turn into splinter and dust. Sometimes the look of an area of debris is like a book picture of a beached shipwreck or an old building whose rotted wooden interiors have collapsed — it’s hard for me not to want the picture to look like something else. The loggers move the debris if it’s in the way, or cut it up for firewood if it’s dry and there’s not too much of it, or simply work around it.

It’s different at the sawmill, where the huts are and where the Germans work in twos and threes on small jobs. I keep my distance there, as well, but not too far. They’re exotic and fun to watch; we get used to one another. If they’re dangerous, they hide it behind their stoicism or a humor that doesn’t translate, which is to say they go their own way or if they do become engaged with me they sort of laugh, sort of smile, or otherwise relax their tight faces as if in spite of themselves. Perhaps they see me as a kind of mascot. Looking back, the situation is absurd. I must be as exotic to them as they are to me or else I remind them of home. They have, more or less, the little freedom of the mill and later on the greater freedom of the woods. As for escape, where would they go that would be any better, and why would they go, since, as everyone says, the almost-over war is far away and Hitler is doomed. Hitler is the word used instead of the word war more often than not.

Around me they show, as my mother would call it, strict manners, but they’re not cold. They treat me with a certain trepidation and curiosity; I treat them with a certain fascination. We both speak a kind of Dutch English. Before they arrived, I hung around the mill and mill’s offices like a fantasy spy, keeping watch on the help at the big machines slowly rendering the raw wood into something useful or checking up on the small talk of the secretaries, busy with typing or filling orders. Compared to the regulars — in the yard or in the office — these Germans move at a different speed, so, of course, to me they add something spectacular, as if they’re playing at the work. I’m probably the only one who thinks so. Those in charge and those who are generally adults seem tense around them, as if they expect to be challenged or suddenly treated to violence.

The Germans, as if naturally, learn the ear-splitting and dangerous ripsaw jobs of the mill with ease, jobs that involve lifting the logs by small crane onto a great table, then unchaining them between vises and making sure they run true into the teeth of the huge saw-wheel that turns like a wheel of fire. First the bark is trimmed, then the naked logs themselves are run back and forth and sized into lumber. The whining of the ripsaw machine is an ear-killing sound — its high-scream octave drives straight to the heart. To save their hearing, the men wear plugs. I simply hold my hands over my ears and stand at a distance, in awe. The resonant smell, too, has power — it’s almost like a drug on the air the way the heartwood odor carries and dominates and makes you cough to clear your nose and throat. It’s the kind of odor you never lose a sense of.

The war, at this point, is wearing out everyone’s patience. My father, at twenty-eight, is in charge here at home, whatever that means. I think what it means is that he’s responsible for the Germans’ and the mill Virginians’ full day of work. He’s at a soldier’s age. He is, in fact, a contemporary of the prisoners he’s responsible for. And these soldiers know who I am. I think they must see in me something of normalcy. And since there is no kindergarten — a German word — they and their schedule represent for me a kind of school. I’m around sometimes in the morning, sometimes the afternoon, breakfast or lunch. What I remember most about breaking bread with them is that they not only work hard but eat hard. They eat tremendous amounts of cheese and eggs and pour milk from heavy diary containers that come directly from the farm, my grandfather’s farm, where the apple trees are. The containers are cold, metal cold; milk is the Germans’ manna from heaven — they often lift the containers to show off and drink the fresh chilled milk flush.

My lasting eating impression is that they take in their food primarily with their hands, very washed hands. They eat rapidly and completely. This all makes sense to me because I envy them their permission to eat with their hands. To be fair, much of their food is intended to be eaten with their fingers — chicken, corn-on-the-cob, boiled potatoes, raw vegetables, apples, and, of course, fresh bread, which they dip into milk. I imagine that some of what war is, is eating with your hands and eating fast. There are worktables in the middle of their two Quonset spaces, where my father sometimes joins me and eats lunch with them. More times than not the Germans prefer holding their plates on their laps sitting on cots or folding chairs. The fresh milk is the best I’ve ever tasted.

Sleep is another thing: those mornings that I follow with my father on a work detail out into the woods, the Germans seem to have slept with the same hard sense of their ultimate mealtime purposes, as if they were eating sleep. The long, hot work hours are part of it; the strict time-frames of the daily schedule are another part; the clarity of their situation is another — their responsibilities are pure. They haven’t lasted long as apple-pickers, planters, or orchard mowers. But they’re a natural for loggers. Their skills on the big table saws and their abilities as a working group have soon moved them to the mill or transported them out among the Shenandoah’s shadows, which is where I first notice what strikes me as their unusual whiteness, their mental intensity, their inherent suggestion of superiority, even if — as I would read years later — “they were in the forced service of their captors.”

They are, after all, Nazis, a self-proclaimed race apart. They have doubtless killed Americans, yes, but also all kinds of people, including children. They have, as representatives, murdered people in their sleep — at least as I imagine. I will be close to seven or eight and the Germans will be long gone before I see the first Pathé half-time newsreel pictures of the concentration camps, let alone the forties’ war movies in which allies are tortured, shot down in cold blood, or sent to the camps or — if lucky in the happier films — successful in making their way out of capture to safety. (Casablanca is the preternatural example of kiss-and-run escape.) Yet, in this moment, in this spring and summer of 1944, at the mill or out in the woods, this sense of this enemy as the absolute enemy, this sense of these particular men as evil fades in close company. They are, at worst, a rumor to me; at best, living, very-present presences.

Who knows what wounded and disabled veterans now home, now here in Winchester, for the rest of their altered lives, think….

But even the barky tone of the Germans’ spoken language — its guttural, blunt-edged, consonantal sounds — strikes me as familiar, human, like someone who is constantly trying to clear his throat. Ich, kartoffel, milch, baum. In the woods, among the echo-chamber stands of trees, their rough dark voices reclarify the silences and give the summer warmth of the trees a ringing feel of abruptness, all business. These Germans don’t seem to me to be bad men, yet by their being here they also imply an ability to reduce the world around them to function, to something they can stand against, even dominate, engineer into submission. I’m a child, an American, so I don’t qualify as important enough to worry the final questions of their future or the future of the war. Insofar as I’m a concern I’m not; their field of vision begins at about a foot or two above my head. Americans, generally, here at home, seem to be beyond their bother. The trees, though, are the perfect challenge, which is why the Germans prove to be so good at bringing them down. I remember this feeling about the trees because I don’t like it and because the trees are alive to me, especially since they must die.

So to me the trees are warm bodies. They’re certainly warm in the summer sunlight. But cut them down, they’re suddenly cold — wounded, killed. That’s the difference between a living tree and lumber: lumber is dead wood, regardless of whatever magical thing you turn it into and how beautiful it can be in its afterlife. Mature oaks and maples and shagbark hickories and black walnuts can run four-to- six and more feet deep and more than a hundred feet tall. Given room to grow they can spread from tip end of a branch to tip end of a branch at least half of what they are high. Normally, though, crowded in a forest, they narrow and elevate toward the sun. They become more like ladders, ready for climbing. Before power tools, band saws are the means of cutting and handsaws the means of culling away the limbs. (The P. W. Plumly logo includes a script that advertises “Band Saw Hardwood Lumber.”)

By hand, forties-era logging is arduous, risky, painstaking work — it takes time, by hand, to humble a tree, to trim and cut it down: hours sometimes; and trees of a certain size you wouldn’t start work on if it was late in the afternoon. The work of the big band saws, in particular, may be a wonder to watch, with a man on each end of a six-to-seven-foot blade, that at its widest is at least a foot, tipped with dinosauric teeth. But it’s a back-breaking business that requires two men in a sort of awkward dance, in a seesaw, tug-of-war rhythm. It’s a rhythm that demands a good number of rests. Yet the Germans turn the dance into something routine, not quite an art, which is to say that they minimize the effort in favor of the achievement. They take their time and save their energy and therefore, ultimately, work faster. And they work through the most dangerous moment of the cutting as intuitively as possible — which I couldn’t then have appreciated — since it involves knowing where at some place past halfway through the trunk the point of departure exactly is, depending on the size and inclination … the point at which the tree begins to accede.

Unlike my father’s usual help, the Germans treat the exhausting job of taking down trees with something like efficiency. The newsreels are constantly referring to “the German war machine”; here — at a ridiculously reduced level — it’s the German tree machine: the work done with dispatch but without apparent passion. It’s as if the better and quicker they do the job the sooner it can be over — not just the day’s job of work but all of it, including the war in Europe and their internment in America. This is how I imagine it now, though at the time the way they worked seemed more like sleight of hand than engineering. Part of it must have had to do with no complaints. The locals were always, it seemed to me, complaining — if it’s not the labor, it’s the weather; if it’s not the extra hour or two, it’s the cold food. Perhaps it’s because they have no choice, but the Germans waste neither time nor energy being personal. As for complaints, they keep their own counsel. The ratio between the height and weight of a tree, it turns out, is personal, individual, and there is no precise predicting how much help it needs in order to make it safely fall. Experience helps, yet the angle of the felling of a tree is predictable only up to where it will likely fall.

Whoever is doing the work — young or old, Virginian or German — an even more dangerous job than cutting is the trimming of the upper-to-lower branches of a standing tree, a one-man exercise, which skill includes strapping onto the tree in a sort of hug as you climb until you reach where you need to be then sawing off, as necessary, various branches and limbs as you walk your way back down. It’s possible, I suppose, to saw as you climb, though I don’t remember it that way. Only the reverse. The important thing is that you do the trimming with care, so as not to be a victim of your success. A suddenly cut-off branch can sometimes work its own will. The obvious advantage to trimming the tree standing is the possible havoc caused by the width of its branches coming down among other trees.

Even so, I hate, from my head-back-looking-up distance and perspective, watching the limbs free-fall, my eyes half-blinded by the sun. It feels too helter-skelter, chaotic, dangerous, plus the noise and the crashing. Even at five, I can see that trimming, in any form, is denuding, an embarrassment to the nature of things.

A great tree without its branching is no longer a tree but a pole rising into dead air. The Germans seem to enjoy this trimming exercise considerably more than the rest of the process, if only because it’s more of an individual challenge compared to the tiring, mechanical byplay of the two-man band saw. As trimming can be tricky, my father’s older help is happy to watch this enemy take the risks. The Germans seem to like, especially, the standing-tree method.

I should say that it has required some negotiation for me to talk my father into letting me come along on these “German” logging trips. Three or four of my father’s regulars, working the woods at a relatively slow pace is one thing; these new young aliens added into the mix is another. There are, if memory serves — at least at the beginning of the work schedule — a couple of National Guardsmen along, more for comfort than protection, to whatever extent the Germans appear to be just fine waiting out the war in my grandfather’s employment Their single escape plot seems to be survival, and they couldn’t plot any better than here where they are. Forties’ war movies set in Europe tend to allow escape routes for Allied spies and POWs — Switzerland, Britain, or some French or Dutch Underground hideout. But here, in Virginia, where would you go, and why? Besides, not all eleven of the Germans are in the field at once; it’s always the safer number of half.

Besides, the Germans appear to take pride in their work. They are inherently strong, their bodies tightly boned, and their skins, when they take off their shirts in the heat, almost lucent with sweat, proud sweat Their minds, too, are lucent, and master, in short order, any of the thinking involved in the labor, starting with the procedure of turning trees into logs, then, with the help of pulley-and-chain, moving the logs one at a time into a mass on the flat beds of trucks. Once on board the men use long axe-handle-like poles to direct the different sizes into a more secure place, after which big chains are wrapped around the whole tiered pile and jacked tight Loading the logs may be even more tricky than cutting the trees. Even so, driving the whole load back down curved mountain roads is the next difficult step, the weight shifting here and there so that you feel it in the cab. And there’s always the unloading at the mill, no less dangerous. My father is always the driver, the Germans always together in a separate van.

Why do I remember horses, large plow horses, instead of only tractors or bulldozers? Horses like the horses at my great Uncle Hub’s farm. Memory is a romance with the past or something you bury as deep as or deeper than a hole in the ground. Why go to the trouble of using horses? But I remember them even if they never existed. And sandwiches, scabby old roast beef with butter on white bread and beer and sometimes sausages and apples, from a two-day supply, before somebody brings more, maybe ham sandwiches and milk, and of course water, in big containers, like the milk. The food, regardless, has the faint taste and smell of pine resin and cut wood and dust off the leaves. And then there is the woody coffee, in smaller containers. There would’ve had to have been grain for the horses, and big water.

This is my family’s business, the harvesting of trees, the way you harvest wheat or cattle. It’s a killing, necessary business. Trees, however, are especially different, not only in their bearing but in the fact that, left alone, they are potentially immortal — immortal as individuals but even more as species and presences to the life on the planet and to human beings in particular, no less so since we climbed down out of them. Bristle cone pines out West can hang on for thousands of years; Great White Oaks in deep forests in the Northeast can last for hundreds. Trees literally stand at the green source of life on the soft earth. As a practical matter they are as essential to our ancestry as to our oxygen supply. And on an entirely different level, they are indelible to the green imagination of the planet. Yet their beauty and necessity are inseparable from their function as timber, even as they represent animate beings, “necessarily sensitive,” writes scholar J. G. Frazer, “and cutting them down becomes a delicate surgical operation, which must be performed with as tender a regard as possible for the feelings of the sufferers.” The Ojibway believe that cutting down living trees is like the wounding and killing of animals; there is silent pain.

From the contemplative outside, trees appear absolute in their stillness, as if they depend on the wind to animate them. But inside they are moving, within themselves, all the time, ring by ring, season after season. Like all living things they grow from the inside out; and like all living things they are alive with fire.

One Shenandoah summer afternoon, I’m wandering around trying to stay out of trouble and trying to find some real shade. Wandering is an exaggeration since you have to be careful where you sit or stand or walk among the clamor and confusion of who is cutting and who is climbing and at what stage the different jobs are. So you have to walk around with sense. I may be waist-high, maybe a little more. The air is hot and wet with an atmosphere richly mingled with the deep, dry odor of the woods. Sound may be muted but it carries. The men are talking their business — in German as well as Virginia English — and the saw sounds and cut limbs dropping and the scattered sounds of birds are all normal and nothing else, until suddenly a scream, no, a shout of pain that ricochets and echoes, like the snaps of a gun, a sound I think the Germans must be familiar with.

One of the Germans, apparently, has been trimming near the top of an older oak, a large one and one that is oddly top-heavy and bent above an open space removed from the light-seeking straighter trees, those less filled out with foliage. You could see, afterwards, how dry the tree was, the kind lumbermen call a burner, since on its own, in the heat, it can ignite. I remember everyone running in the direction of the shout. By the time I get there it’s clear that one of the thinner cut upper branches has blown up into the hand not holding the saw, the German’s left hand, and has penetrated the palm with splinters the size of wood spikes, some as large as the sharp ends of pencils. In spite of it all, he has managed, amazingly, to walk his slow way back down on the limbs that are left. My father, who is no doctor, pulls out each of the spikes with care, washing and pouring iodine over the mass of the wounds. Then he wraps the hand in gauze and tape and we call it a day. All this while, except for that first moment of as much surprise as pain, the German soldier has been silent.

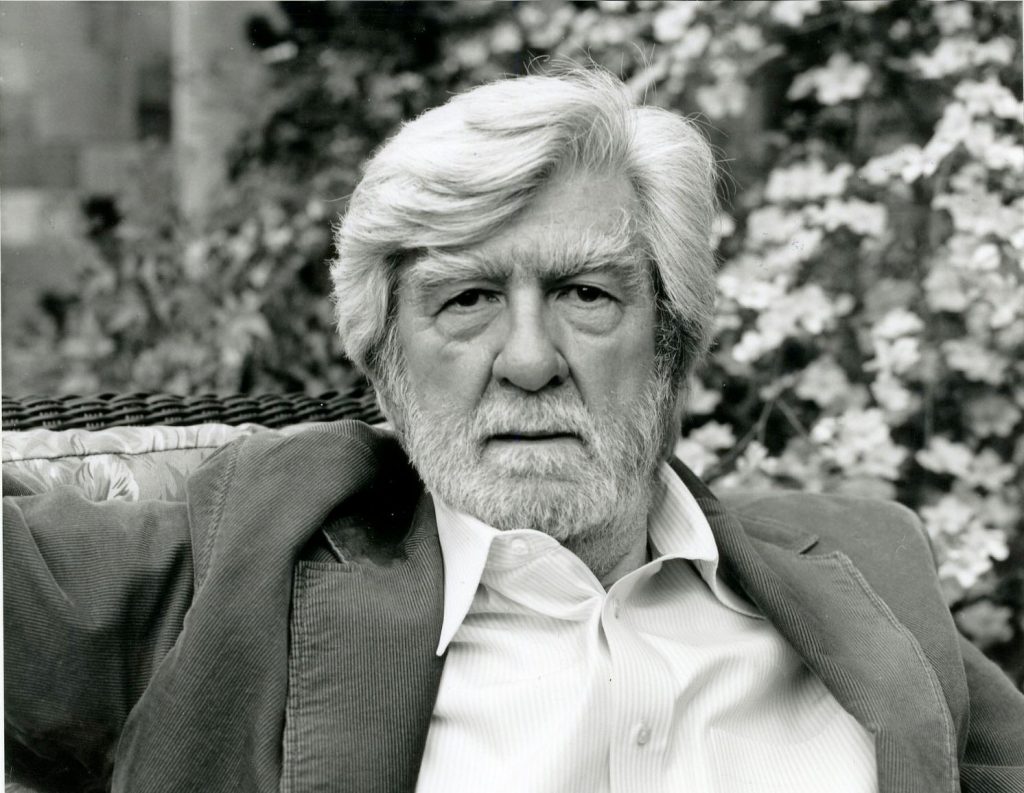

STANLEY PLUMLY has authored ten books of poetry and four works of nonfiction, including Elegy Landscapes, Posthumous Keats, and The Immortal Evening. Winner of the Truman Capote Award, Los Angeles Times Book Prize and the Paterson Poetry Prize, among others, Plumly teaches at the University of Maryland and lives in Frederick, Maryland.

More by Stanley Plumly:

Two poems in B O D Y