PRAGUE AND MEMORY

Editor’s Note: This is the third installment in a three-part series of a new work by American poet and critic Burt Kimmelman.

Read Part I here

Read Part II here

____________________________________________________________________

History

Living in Bohemia, we come to realize we’re in a different part of the world. If you look quickly it all seems familiar. But then you begin to notice a few things.

Two historical turning points must be kept in mind, when trying to comprehend contemporary Prague. One is the Velvet Revolution in late 1989. The other is the formation of Czechoslovakia, seven decades before, more to the point its First Republic, in 1918. Before Václav Havel became the nation’s President, in 1989, the Czechs had been living under foreign rule for three centuries. The twenty glorious years of the First Republic—once sovereignty had been granted collectively to Bohemia, Moravia and Slovakia—were a flowering of democracy, the creation of an open society.

The First Republic, modeled on the US political system, came into being because of the vision and drive of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, who was married to an American woman, Charlotte Garrigue. (Out of respect for her, he took her maiden name as his middle name.) American democracy was foremost in their minds. The Czechs and Slovaks had compelling geopolitical reasons to join together then. The new nation of Czechoslovakia was formed at the end of the Great War, as it was called. In return for Czech and Slovak support of the Allies in the war, Woodrow Wilson prevailed upon the League of Nations to sponsor the new sovereign state.

Different culturally, speaking somewhat different languages, Czechs and Slovaks share a singular experience in all of Eastern Europe—that of a robustly free, self-determining society. It’s said that the new nation was the most democratic, functioning, thriving democracy on the continent. In 1938, the Nazis marched into the so-called Sudetenland, and the rest of Czechoslovakia the following year—the direct consequence of the Munich Agreement or what the Czechs still call the Mnichovská zrada (the Munich Betrayal).

The Cold War had already begun by the conclusion of the hot war, coalescing before everyone’s eyes. People watched it evolve. By pre-agreement, at the end of the Second World War in 1945, the Western forces stood back in order to allow the Soviets to liberate the Czech and Slovak territories. Two Czech factions vied for power (one headquartered in London, the other in Moscow, during the war). The Czech Communists—more ruthless, ignoring legal niceties—would seize political control. They officially won the election of 1948 and then invited the Soviets’ assistance. Life under the sway of the Soviet Union officially began then, yet such an outcome had been imagined by the time the Germans were being rounded up for imprisonment.

That the Czechs played a unique part in the Cold War is not merely an incidental fact. Czechoslovakia officially, having embraced the Soviets, suffered less deprivation than all other citizens living behind the Iron Curtain. While Communist rule was sinister, often cruel and cynical, Czechoslovakia’s material standard of living was better than even that of Russia. The Czechs were handled from Moscow, to borrow Havel’s phrase from “The Power of the Powerless,” with the “gloves on.” (In contrast, the Charter 77 dissidents, along with Havel, received the bare knuckles treatment.) The Czechoslovakian version of Communist control was terrible in its own way, to be sure. Beyond any physical abuse or impoverishment, the government’s control was truly Orwellian.

The story of Pilsen makes this point emphatically. Pilsen became a prime example of totalitarianism. The city of Pilsen and its vicinity were liberated by Patton’s forces—unlike everywhere else in the country and contrary to the allies’ 1945 agreement to let the Soviets enter Czechoslovakia first. The Communists now officially in power—including in Pilsen—clergy and artists, intelligentsia and all known dissidents were imprisoned or executed. There were some show trials. Only in 1990, a year after Communism’s fall, did the memorializing of the city’s liberation by American soldiers commence again, since 1948.

All of Czechoslovakia would eventually become part of the Warsaw Pact configuration, the Soviet Union and its satellite nations. During the Communist years, the people in Pilsen and the small towns around it, freed of the Nazis by the Americans, acknowledged to each other and to their children what really happened—Patton’s army had saved them from the Nazis’ further depredations. Publicly, however, the Czechs parroted what became the Communist official history, which held that Russian soldiers had removed the German forces. It was even claimed, as part of official Communist historiography, that some Russians had been wearing American uniforms in those early May days in 1945, uprooting the German forces, setting the Czechs free. This story was meant as a retort to a common, rash exclamation among the Czechs: “But I remember the American soldiers in their uniforms!” The question to be asked about this official lie, now, is whether the doubleness was the intention.

* * * *

Pilsen is the fourth largest city in the Czech Republic. It’s the home of pilsener beer, and of the Patton Museum. Patton placed fifth in the first-ever Pentathlon in the Olympics, in 1912. He is fanatically worshipped here. His life and deeds constitute, in Pilsen, a hagiography. That he is often viewed by Americans with a gimlet eye is a surprise to the Czechs. Once that point of view is shared, it’s quickly let drop—down the memory hole.

Patton officially liberated Pilsen on May 6, 1945, his soldiers first engaging the enemy there two days earlier. The annual celebration of the liberation begins on May 4th. Diane and I attended the opening ceremony. A huge congregation of locals and press was packed into the opera house, to hear from surviving American and Belgian vets who had carried out the military assault. A great many high-schoolers were present. The event went forward in dignified, stately pomp.

Over the three days, some eccentric version of Mardi Gras unfolded. Probably a thousand people—who were among more than ninety-thousand taking part in this three-day bacchanale—had dressed themselves in World War II American uniforms or 1940s civilian garb and makeup.

They clogged the streets and squares, along with hundreds of vintage US jeeps, armored cars, tanks and trucks. A parade of these vehicles, driven by American-uniformed celebrants, took nearly two hours to pass. Surviving veterans were seated or standing, one to a jeep, waving at the crowd lined up along the avenue, and Patton’s grandson was an honored guest, he too waving at us from a passing jeep. Two American fighter jets flew over us, wagging their wings in a salute. Then came two vintage fighter planes, single engines buzzing, flying back and forth along the same path.

It was beautiful weather. That evening, the Count Basie Orchestra was the featured event in the town’s main square. A couple of thousand people danced, drank beer and ate a variety of foods, milling about on all sides of a church with its tall steeple. There was some great jitterbugging—ecstatic. People were still in uniform, and stayed that way for the full three days. The best of the bands we heard, the next evening, was a fabulous Blue Grass ensemble (an artifact of a back-to-the-land movement that predates the Nazis). All their lyrics were in Czech.

When, on the sixth of May, 1945, the commanding German officer along with ten thousand German soldiers stationed in Pilsen surrendered, some Czech collaborators were also arrested, with the aid of Czech resistance fighters. The next thing the German commandant did, after signing the capitulation document, was to shoot himself. At the same time, American soldiers were methodically firing at German snipers who were, in turn, trying to pick them off from upper-story windows and a bell tower. Their skirmishing is vividly on display in archival footage that is shown in an endless loop at the Patton Museum.

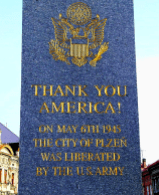

The closing ceremony was held at the Czech-American War Memorial featuring two towers, one inscribed in Czech, the other in English. The Czechs in Pilsen are deeply grateful to America for freeing them from the Nazis—but also from the Russians and their allies. We were told that the festival is an expression of great relief for having gotten free of the Soviet Union’s grasp. It’s clearly not forgotten. Each year this mock-up of the American war is presented—not any fake battles as you’d see in the States, but, even so, replicated bivouacs, that sort of thing—as people celebrate with a vengeance. They’re making up for lost time.

East-West

Before we left for Prague in January, we attended a superb staging of a play by Egon Bondy, Havel’s contemporary and theatrical rival, at the Bohemian National Hall in Manhattan. The deeply disturbing drama, titled The Visiting Experts, was written and performed in Slovak (with supertitles in English). After the Czech-Slovak separation in 1993, Bondy chose Slovakian citizenship.

The storyline disappears within a phantasmagorical surrealism. The plot is simple: two experts visit two other experts in another country, to study their methods of state-sponsored torture. Torture is random. Only Russia is mentioned, its secret-police methods compared with the other two countries’ and said to be not as gruesome. I don’t think an American actor could have adequately rendered any of the drama’s four roles. After viewing that drama, I began to grasp why, in Eastern Europe, the West is considered soft, weak, and decadent.

On our flight to Prague, I read an article by Masha Gessen about some brave Russians who had located, marked, and were now honoring a killing field and burial ground with a public ceremony. Gessen covered the event. Aside from the now well-documented Katyn Forest exterminations, thousands of executions of Poles at this new site had gone unacknowledged. The Russians had systematically massacred them. The mass burial ground contains their bodies. The Russian citizens who created the memorial did so at risk to themselves.

On our first evening in frigid Prague we had some delicious, restorative, hot soup in a nearby restaurant. At that moment I adopted a mantra that I’d hold to myself throughout our time there: “soup and murder.” I would come to learn about the ravages of the Czech Communist regime.

The Vltava River meanders northward through the city, nearly looping back on itself at one point. Ten degrees Fahrenheit felt especially cold. Prague is based on that river; life in Prague is conditioned by it. This is why (as I’ve suggested) the city has evolved over time into the thing of utter beauty it is. And this is why Czechs traditionally have soup twice a day in the winter months. The French military campaign of 1812 ground to a halt in the snows of Russia. So did the German invasion, marking the decisive turn, in the Second World War. What do beauty and endurance have to do with one another, if anything? The Czechs have endured for half a millennium.

On the other hand, the fact that the Czechs and Slovaks share an experience with the West, one simply lying outside the scope of the rest of Eastern Europe, including all of what is now the Russian Federation, makes me think about what it means to be civilized. For all their great art, architecture, literature, music, philosophy, food, drink, and so on, the peoples of the East have never really known democracy, but for the Czechs and Slovaks. A Czech friend observed that it takes time to learn to think democratically, to harbor expectations of what a democracy implicitly promises, what it also demands, to insist on one’s rights.

* * * *

The Czechs became subjects of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the year the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock, 1620. Prague’s grand castle, at times the seat of Holy Roman Emperors, would be put to other uses. During the Austrian rule of more recent times the Czechs would learn which streets in Prague, which hotels, restaurants, cafés, theatres and opera were off limits. The boundaries, at times unspoken, were inviolable.

Given that the language of power was German, it’s striking how little of this language made its way into Czech, even allowing for the difference between Germanic and Slavic language groups. The difference is cultural. In some respects, whatever else might have been in play during the centuries of subjugation, Czechs could not ignore the history of Bohemian relations with France and Italy (as well as with Prussia and Austria) in the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

What of the other Slavic nations? It’s said that the Czechs’ relationship with the Poles, who share a common border, is like two people who are standing with their backs to one another. So much is the same. So much is different. During the Cold War, dissidents from the two countries used to meet secretly at the border.

The Czechs, like the Poles and Germans, are beer drinkers. The Czechs consume more beer per capita than any other nation. It’s said that all things get really discussed over beer. The Poles also consume vodka, like the Russians. The French and Italians drink wine, as do the Germans and Austrians.

* * * *

Slavonice is a story of German and Czech. This small town lies a kilometer from Austria. It’s not far from the Slovak border and closer still to Brno and Vienna. There’s a larger truth in this geography. Located in southwest Moravia, Slavonice is now said to be a part of the South Bohemian Region. The town’s character is the result of complex cultural, geopolitical, and linguistic mixings over extended periods of time marked by sudden upheavals.

The border with Austria runs along a hill. During the Cold War, the hill featured a 3,000-volt electrified fence, within eyeshot of the town. A low-lying stone wall behind some houses would lead one’s sight off to it in the distance. It was a weird, subliminal experience, people told us, to live on the Czech side of that hill, especially knowing that the fence was lethal.

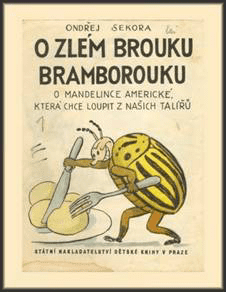

The pages of what had once been a popular children’s book, during the Cold War, are filled with lovely illustrations. The book was read to Slavonice’s children. It’s about a bug infestation that ruined the American potato crop one year (those stupid, capitalistic Amerikanski!). The bugs are quite cute. We found the book on display in a gallery in the town, when we visited there.

The town has a community arts center now. The building was constructed by the Soviets and was meant to be a commons, a leisure center for Communist elite who were allowed to live in the town or its periphery. Slavonice was part of a restricted zone then. No one got in without first undergoing intense vetting.

The town had been a major stopover along a trade route in ancient times (the principal exchange was amber for salt). Much later, Slavonice was a stop on a postal route connecting Prague and Vienna. Sometime after the postal route was in place, a rail line was completed between the cities. Jewish merchants produced textiles in Slavonice, which were bought in Vienna, transported there by train.

There have been various regimes under which the town has survived as part Czech and part German. In 1938, the town was occupied by the Nazis (who claimed Slavonice and its environs as part of the Sudetenland). Many of the Czechs were removed then, as were all of the town’s Jews to concentration camps. At the end of the war, Slavonice’s German families were uprooted in a single night, after living there for four hundred years. Seven families were allowed to stay because they could prove that they were anti-Nazi, which, in the circumstances, was nearly impossible to do. Six of them were of mixed marriages.

The Germans being expelled were allowed to take no more than thirty-eight kilograms of belongings with them. They were given a half hour to pack. Elsewhere in Czechoslovakia, Germans and Austrians suffered a similar fate at the war’s end. In Brno, the Czechs’ second-largest city, twenty thousand Germans were hastily marched fifty kilometers out of the city. Two thousand of them died along the way.

After the expulsions following the war, Slavonice was repopulated entirely by Czechs. In more recent times, the grandchildren of that 1945 expulsion were welcomed into Slavonice by the Czechs living there. Many of these Czechs were the grandchildren born since the expulsion, who had grown up there.

Slavonice is famous for its Renaissance sgraffiti on the sides of some of the buildings and for frescoes within them. An enlightened Czech ruler had invited Italian and French artisans to come there at that time. Some of the sgraffiti is still being uncovered and restored.

As much or more German is spoken in Slavonice today as Czech. The town is a major arts destination now. Really, it’s a live-in museum. But many tourists show up mostly to eat and drink in the cafés on the town square, where they admire Slavonice’s beautiful buildings, towers and fountains—which exist both in and out of time.

* * * *

Czech was always an underground language. The first Czech dictionary was created only at the turn of the twentieth century, derived from a 1870 translation of the King James Bible. Czech literature didn’t start to be written until the mid-nineteenth century. Czech, more to the point Bohemian, humor, similar to that of all Eastern European cultures be they Slavic or not, is nonetheless unique. It’s quite different from what’s to be found in German or, generally, Western European cultures.

Czech humor is quirky and uniquely dark. It’s not that the Czechs don’t also possess a drollery —as do the Russians, Lithuanians, Poles, and Romanians. It’s more that the Czechs, especially the Bohemians, own a viewpoint that gives them insight into the ways in which power and grace may coexist, thus a delicate humor that takes irony for granted. It’s extremely incisive, wickedly hilarious. The Czechs’ history helps to account for this.

In explaining the Russian mindset, in another article, Gessen recalls a remark by Slavenka Drakulić (who is Croatian): Being able to laugh was, Gessen says, “the ultimate personal triumph over the daily humiliations of life under Communist rule,” including in Russia. Gessen can’t resist sharing a current Russian joke that goes like this: Putin opens his refrigerator and the “jellied meat begins to quake, but he reassures it by saying he is getting the yogurt.”

The joke is blunt. It expresses unmitigated power, as if that could be the entirety of the human experience and without consequence. Gessen’s purchase on America’s political paralysis these days is, along with our cultural dilemma more broadly, required reading. But it’s Russian. In other words, it’s different—slightly, yes—in certain key ways.

Russians have, in their history, often discovered themselves in the role of overlord. Russian has always been a dominant language. Czech, also a Slavic language, has been a language of abjection for nearly half a millennium. It has been spoken by people who have been forced to live under the rule of others.

Epilogue

On Easter Monday, Diane and I set out to visit Terezín. We had no idea that everything in Prague, including most buses leaving the city, were to be in brief hibernation that day. The Easter Sunday was a bustling, big, festive day, the holiday mostly a good time out for families who shopped and dined. (The Czechs are, for the most part, atheists.) Prague was abuzz. Monday was silent. There was no notice anywhere, online or at the bus stations, that the bus from Prague to Terezín would not be running.

The Nazis renamed it Theresienstadt. Terezín is an hour’s drive from Prague. We did manage to get there a month later. Like the Czech Roma, who were collected in the Lety concentration camp near Prague, nearly all of the Terezín inmates in both the prison and ghetto (comprised of Jews and non-Jews, many of them Czechs) were shipped to their deaths in Auschwitz. Many didn’t live long enough to make that last journey.

Once the Communists took control, anyone deemed to be potential trouble for the regime was imprisoned in a far-flung facility and put to work nearby in a uranium mine. Among these prisoners were former Nazis. The prison administration soon recognized that these people had a particular talent, so they were elevated to serve as something like the Auschwitz capos. What these Czech Communists saw in their Nazi charges was a likeness. They were soulmates.

* * * *

The first of May, called Labor Day in the Czech Republic, is a major holiday. Yet Prague was empty and silent. I sat alone in a café, reading and writing over coffee. My waiter, with little to do, hung around to talk. I commented on how deserted not only his café but also the whole neighborhood was. He said, simply, that everyone had gone to their country houses for the long weekend.

He volunteered that the custom of retreating from the city to the family’s country cottage had become all the more cherished once the Communists took control. Alone in your house in the country, with your family, you were free of surveillance. You could relax, and talk as you wished. The Czechs who were children under the Communists tell about how, back when they were kids, they knew full well to adhere to a different story of family life and conversation, once they stepped out into society, through the door of their home.

* * * *

Diane and I had been the special guests at a bytový seminář (an apartment salon or group discussion in someone’s home). Such a get-together used to be clandestine. The custom hung on after 1989.

There was plenty of food. Children were also attending. The evening’s topic was the Sixties. The adults were mostly in their fifties. They listened intently. Later, they asked questions and made some comments—following Diane’s reading of one of her short stories that takes place in that period. The story had been translated by one of our hosts, who read the story in Czech after Diane’s pauses in her English. The Prague Spring of 1968 was prominent in these people’s minds, and they came to the seminar knowing what a disruptive year it was around the world.

The discussion went on from Diane’s story, the two of us sharing remembrances of the period. At the end of the evening we had to rush to catch the last train back to Prague. Before we left, we signed some people’s logs; these were their diaries from past salons they’d attended. Diane and I were there for their fortieth meeting.

* * * *

The Museum of Communism is situated on Náměstí Republiky, one of the largest plazas in Prague and one of its major shopping and transportation hubs. The young people who were viewing the museum’s exhibits the day we were there looked somber as they listened to recordings and watched videos. One young woman, in her early thirties, was weeping over some film footage shown on a TV monitor. It was of a demonstration in Wenceslas Square. The police were beating and arresting people. There was a palpable fear as well as bravery in the faces of these people, who were demonstrating against the status quo.

I don’t know how informed these kids in the museum were, but they surely knew of the recent Czech elections. They might not have known of Italy’s swerve rightward in its recent election, which was just in the news. These visitors to the museum were mostly people who did not live under the Communist thumb.

Various exhibitions in Prague are meant to report on the Communist years. These exhibitions would typically feature documents of show trials, executions, prison sentences to hard labor—sentences usually handed out to intellectuals, artists, priests, and others who were deemed to have been potential trouble. The exhibitions were not well attended.

The world outside the Czechs’ door is so very different from what, let’s say, the people involved in the Charter 77 movement protested against in the eighties, and before that transition period too. As artists and musicians who made up the movement, they were initially interested in art for its own sake. After rallying against the arrest of The Plastic People of the Universe, a rock band, they too were arrested. Their acts of defiance, their persistence, and their martyrdom (the many interrogations and prison sentences, in some cases resulting in death) drew international attention.

I think again of the general disillusion that set in when Soviet and Warsaw Pact tanks showed up one morning on Wenceslas Square, in 1968, which I saw documented in photos mounted on the walls of Lucerna, and at a more extensive exhibit about the Prague Spring.

Once again I feel puzzled that people had been caught flat-footed, given the drift in Czech society at the time toward liberalism. In a natural evolution, the people were starting to act a bit more freely, starting to modify the country’s social and economic policies. There had to be a move to squelch that.

* * * *

The good old days of Communism are still fondly recollected in Prague and elsewhere by senior citizens. It seems to be a malaise that hangs on, yet, when these people have passed away, hopefully a subsequent election will choose a stronger alliance with the West. Nostalgia is a powerful force that may, in the Czech Republic, be indistinguishable from the profound psychological trauma I see the young people struggling to transcend in creative, exciting ways.

I think for instance of the Vnitroblok Café that was also a sneaker store (there is an innumerable variety of sneakers worn in Prague, among all cities, I’d say) as well as an art gallery, a dance studio, and, in its courtyard, a cheeseburger and pulled-pork restaurant whose kitchen, equipped with its own soundtrack, was set up inside an American school bus that had been shipped from Cobb County, Georgia, license plate and all (the soundtrack inside the café proper comes from a full-time DJ). You see this sort of innovation everywhere in Prague—in the cafés, on the streets, in the way the young people dress, in their guarded insouciance I hope never to forget.

* * * *

In 1989, the Berlin Wall having come down—the Soviets exhausted, their empire disintegrating—the Czechs gained their freedom once again. Short of two months from the moment of the Czech rebellion that year (the Soviets let the Czechs know they’d not intervene), Havel was sworn in as President. He was, at first, not as well known to the public as two other dissident leaders. But the CIA put its money on him and, overnight, some Czech friends told us, there were Havel posters and other paraphernalia everywhere.

He presided over a new, in many ways unknown, world. Czech society was about to figure out who and what it was. For strategic reasons, needing to keep a coalition together in order to govern, he didn’t insist that the Czech Communist party be dissolved.

* * * * *

Life in the New York metropolitan area, as I look back on what was another world, a life in Prague, can seem a puzzle. We live in a leafy suburb, less than an hour from midtown Manhattan. We know the drill. Flying back into Newark-Liberty airport, the massive controlled frenzy of reentering America, then a car ride to our leafy, pretty neighborhood, I felt grateful for the quiet; the calm nights are a reprieve from my having to compensate at every turn for what had been normal. The night is a salve. In daylight I try to make sense of the disjunct between the there and the here.

Everything, now, in the United States, has become uncertain—in a way I’d come to feel was integral to life in Eastern Europe not that long ago, and now is, increasingly, in Western Europe. Diane and I spend our free time working to win back the US Congress for the Democratic party, in what we see is an unqualified national emergency. We don’t have the time to indulge ourselves in the niceties of adjusting to being back. Yet it all sinks in.

Aside from the soaring beauty of Prague—the visual grace of its architecture, the often subliminally disruptive nature of its art, which I found to be so very compelling, and the grandeur of its symphonic music we got to hear at the Rudolfinum that is surely the most sumptuous, gorgeous, elegant concert hall anywhere—the history of Europe, all its self-inflicted tragedies, is helping us, our knowledge of it up close, in America’s fight for its soul.

____________________________________________________________________

Read Part I here

Read Part II here

____________________________________________________________________

BURT KIMMELMAN has published seventeen books of poetry and criticism, and more than a hundred articles on literature, art and other matters. His poems are often anthologized and have been featured on National Public Radio (in the United States). Interviews of him are available in print or online. His ninth collection of poems, Abandoned Angel (Marsh Hawk Press), appeared in 2015. A new collection, Wings Apart, is due to be published by Dos Madres Press next year. He teaches literary and cultural studies at New Jersey Institute of Technology. More about him can be found at BurtKimmelman.com.