MY SEVEN LIVES

The second of three excerpts from Agneša Kalinová’s memoirs

Agneša Kalinová in conversation with Jana Juráňová

After the war, she married the writer Ján Ladislav Kalina (known as Laco) and went on to become a leading journalist on the weekly Kultúrny život. In the days following the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia thousands of people left the country before the borders were closed, including many of those who had been involved in the reform movement known as the Prague Spring. Agneša Kalinová, with her husband and daughter, left for Vienna but chose to return to their home in Bratislava a few weeks later. In this passage Agneša Kalinová describes the demise of her newspaper, Kultúrny život, and of her journalistic career as the country was “normalised”.

“Did you go on working for Kultúrny život?

On the day we came back from Vienna I attended an editorial meeting at Kultúrny život (Cultural Life). It was held in the evening, something that had never happened before. The paper had not come out since a special, shortened edition appeared immediately after the invasion, and we discussed the fact that nearly all the other newspapers had started appearing again, some under slightly altered titles. We decided we would try and salvage what we could and that we would stick to our guns in terms of our political line because in those days it was still far from obvious that everything was truly lost. There was a lot of resistance among the population, the Russians were still delaying taking administrative and political decisions, and we were under the illusion that we might be able to pull things off for a while longer. So we decided to keep publishing the paper but since it would no longer be the same Kultúrny život, we would change the title to Literárny život (Literary Life). Two days later we were notified by the Slovak Writers’ Union that in order to change the title we had to re-register.

Presumably this wasn’t a coincidence?

Certainly not: re-registering with the authorities was just a pretext for getting rid of Kultúrny život. They simply refused to register us. But they didn’t say so outright. The decision dragged on, even though the Writers’ Union immediately appointed Dominik Tatarka as the new editor-in-chief. Our editorial office was in Štúrova Street, and we’d turn up every day at 9:00 or 9:30 am – basically just to wait for Godot, but as he wasn’t coming we’d just hang around chatting and exchanging the latest news. We were depressed: the situation was hopeless and although we kept drawing our salaries we had nothing to do. This went on right through the autumn.

Meanwhile things were hotting up at the Writers’ Union. Those who had never been too keen on the reforms kept silent, while others tried to muster support and write petitions asking the Union leadership to take more decisive action on behalf of Kultúrny život. By then Gustáv Husák had been installed as Secretary General of Slovakia’s Communist Party. We heard rumours that Kultúrny život wouldn’t be re-registered unless three people left; the names mentioned were Rudo Olšinský’s, Kornel Földvári’s and mine, although nobody would officially confirm that. Tatarka refused to go along with this as a matter of principle and when he learned that this wasn’t just empty talk he stepped down as editor-in-chief designate of the would-be Literárny život. (….)

How did your career with Kultúrny život come to an end?

By early 1969 it became obvious that the call for the three of us to leave was the key condition from “high up”. Unless we went the new Literárny život wouldn’t be registered. Kornel Földvári left sometime in early 1969, when he was offered the job of director of the Korzo Theatre. As of 1 March our official employer, the Slovenský spisovateľ (Slovak Writer) publishing house, terminated mine and Rudo Olšinský’s contracts. To cover up our dismissal, which was imposed on them by the authorities, they pretended we were leaving by mutual agreement. I wrote a long letter protesting that no such thing had ever been agreed with me. About a month later Literárny život was registered and its first issue came out. [The critic] Milan Hamada became editor-in-chief and Jozef Bob stayed on as his deputy. Literárny život appeared from May 1969 till the end of August of that year, with some six issues altogether. Sometimes I would drop by the office for a chat, we were all friends after all.

What did you do after that?

Right after I was fired, the Prague bi-weekly Filmové a televizní noviny (Film and Television News) offered me the post of their Slovak editor. I had a fantastic time, I worked from home, I’d file my copy – I’d write a column or a review, or interview someone in Bratislava, I’d make some calls commissioning additional articles in line with what was decided in editorial meetings. I think this was the nicest job I ever had. In those days there was still a lot going on in Slovak cinema, a second wave of young Slovak directors had just emerged – Dušan Hanák followed up on his earlier, remarkable documentaries with 322, his first feature film made in a similar vein; Juraj Jakubisko, who had caused quite a stir with Kristove roky, his graduation film at the FAMU film school in Prague, which was like a breath of fresh air, amazed everyone in 1968 with his short Zbehovia a pútnici (The Deserters and the Nomads). It wasn’t just the fact that he managed to sneak in some documentary footage of the Soviet invasion into the film, what amazed everyone was the explosion of colour in the film and his expressive storytelling, more Paradjanov than Forman. His next film, Vtáčkovia, siroty a blázni (Birds, Orphans and Fools), which was even more outrageous and a riot of symbols, ran afoul of the new, sterner criteria in Bratislava and enjoyed only a very brief run in the movie theatres, and he wasn’t allowed to finish his next film, Do videnia v pekle, priatelia (See You in Hell, Friends). But I managed to publish a report from the film set.

So at this stage you focused solely on movies?

Yes, on movies and on translating. And in May 1969 I received a written invitation from the management of the Berlin Film Festival to serve on the jury of the international Berlinale. This was my first visit to West Berlin and I was very impressed: it was dazzling, vibrant and all lit up, but to come face to face with the Wall, which sliced the city right down the middle, that was a shocking experience.

The jury met right away, I was even elected deputy chair and we were introduced at the opening ceremony in the Palais de Festival. Some three days later I was summoned to the Czechoslovak Military Mission (that was the only official representation the country had in Berlin in those days) and was told that the Soviet comrades were upset that I was the one representing Czechoslovakia on an international jury. The people at the Mission said that they were also baffled about this since Czechoslovakia hadn’t entered any films in the competition. And they demanded that I should resign and make a public statement to that effect. They showed me a press release they had already sent to a press agency. It said that since Czechoslovakia wasn’t participating in the festival as a matter of principle the country hadn’t delegated anyone to represent it on the jury, and therefore I – here the press release mentioned me by name – was not representing Czechoslovakia.

I was rather taken aback to hear that the news had already appeared in some newspaper. I took a deep breath and told them I wasn’t there on behalf of Czechoslovakia, that I wasn’t representing anyone and that I had been personally invited to be on the jury in my capacity as a film critic and therefore I was there on behalf of myself. And that I wasn’t aware of any films I should be protesting against and saw no reason to resign from the jury. This made it into the news and one Berlin newspaper kicked up quite a fuss. In those days Czechoslovakia was still very popular in the West so everyone wanted to know how this would end.

So suddenly I became a great hero, and everyone wondered what was going to happen and whether I’d be in trouble after my return. But nothing happened. I wonder if the people at the Berlin Mission had just put it in the bin without ever reporting back to Prague. Nobody at my paper in Prague had taken any notice, they had other problems. In fact, this had never been specifically held against me, neither in Bratislava nor in Prague.

How did you see Husák’s role in the “normalization”?

Now that you mention it, I realise that Husák played exactly the same role in 1968 as he had in February 1948. Back then he’d also been in charge and in the autumn of 1947 he’d carried out a kind of dry run for the 1948 February communist takeover. Now he tried the same trick again. In his capacity as First Secretary of the Central Committee of Slovakia’s Communist Party he staged a kind of mini pre-normalization in Slovakia at the time as people were still trying to salvage as much as possible. In Prague this process took a whole year but from his seat in Bratislava Husák tried to accelerate the process in Prague as well. One of the reasons why things took a turn for the worse in Slovakia was that many intellectuals who had been active in the reform process and who had voiced some demands then, felt satisfied when the federative system was introduced and Husák rose to a leading position in Slovakia. They stuck with him, believed in him and made loyal noises, generally doing Husák’s bidding. Partly because they trusted him and partly because they felt that their key demand, i.e. federalization, had been achieved, there wasn’t much more for them to be concerned about.

Some expressed the view, which became even more common during the normalization, that if it hadn’t been for the Czechs and their radical views the invasion needn’t have happened, so why should we identify with the Prague-based extremists? In fact, many Slovak Writers’ Union officials had regarded as extremist the speeches delivered by Ludvík Vaculík, Milan Kundera and Pavel Kohout at the Fourth Writers’ Union congress in 1967, feeling that they had been unnecessarily provocative and extremist. And these writers started rising in the hierachy one by one as cushy jobs were to be had in both Bratislava and Prague. The poet Vojtech Mihálik had protested the August 1968 invasion by writing The Song of Danka Košanová, a poem dedicated to a young girl shot dead by the Red Army, and by signing every petition to the Prague parliament, as did [Miroslav] Válek, who served as Minister of Culture. Both were soon rewarded with positions in the new system, which flattered their vanity and satisfied their financial demands. So in Slovakia things were calming down, partly thanks to Husák‘s policies as well as his authority. And the fact that he succeeded in this made him rather attractive in the eyes of the Russians.

In his book Seven Days to the Funeral Jan Rozner wrote that in the end Slovakia had always profited from every crisis. Would you agree with that assessment?

The only real benefit and the only tangible outcome of the burgeoning reform movement that lasted from January 1968 until the August invasion was the adoption of the constitutional law on the federalization of Czechoslovakia, which came into force with a great fanfare on 27 October 1968. It guaranteed Slovakia a position equal to that of the Czech part of the country, at least formally. This was generally seen as a great achievement, and as a result some optimism returned to Bratislava: people in Slovakia felt gratified and reassured, and they showed greater willingness to come to terms with the new situation. We must remember that throughout the preceding period one of the most hotly debated issues was the question of which was more important: democratization or federalization. Opinions on this subject were divided, even at Kultúrny život we had split into two opposing camps. Now that the supporters of the federation had won, their option turned out to have been the easier one. The Russians didn’t really mind that either, because in fact federalization echoed the Soviet system: the USSR also had union republics and autonomous regions within them. However, as soon as the term “normalization” was introduced it became abundantly clear that the system had not changed in any substantial way. Quite the contrary: the clock was turned back to something resembling the 1950s, complete with communist-style “democratic centralism”. The “all-powerful party” continued to rule from a single centre, Prague, except that the Slovaks, who had swallowed the bait of federation, were offered more jobs with impressive-sounding titles and better salaries.

Did you observe any signs of nationalism at that time?

Nationalism reared its head as early as in the 1960s when the struggle for federalization began. For example, I remember that in 1968 some young men from the Svoradov student hall marched through the streets of Bratislava singing the wartime Slovak fascist song “Rež a rúbaj do krve” (“Slash and chop till you draw blood”). That came as a real shock to me. They were university students. There weren’t many of them and nobody made much fuss about it, but I remember it all too well.

Then came 1969: what was its significance?

The year 1969 was the concluding chapter of this period. It all started with the “Palachiade” – the self-immolation of the student Jan Palach in protest at the rising indifference in society. For a while it seemed that the shock had jolted people out of their lethargy, that some of the heady atmosphere of the days immediately following 21 August 1968 was returning. This brief change of atmosphere also found its expression in the almost hysterical celebrations after Czechoslovakia’s victory over the Soviet Union in an ice hockey match; in Bratislava, too, there was a huge rally during which the police beat up the translator Zora Jesenská, who described this experience in an essay for the Prague paper Listy. And then the doors slammed shut: in the spring Dubček was deposed and replaced by Gustáv Husák as First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia.

That was the real beginning of the end. On the first anniversary of the invasion the police cracked down harshly on protesters in Prague and Bratislava, and in the fall of 1969 the borders where closed for good. Normalization was officially launched in January 1970, with purges and expulsions from the party and many people losing their jobs. By the end of 1969 Listy had stopped appearing in Prague, as had Filmové a televizní noviny and every other journal of a similar orientation. The year 1969 put a stop to every reform movement and aspiration and extinguished the hopes that had been nurtured since Stalin’s death and solidified in 1956, when the illustrious leader of the proletariat was denounced in Moscow, launching more than a decade of a bizarre dance: one step forward and two steps back, then the other way round. But now that dance was over and from now on there was only one direction, set by the party and government policy: backward march!”

____________________________________________________________________

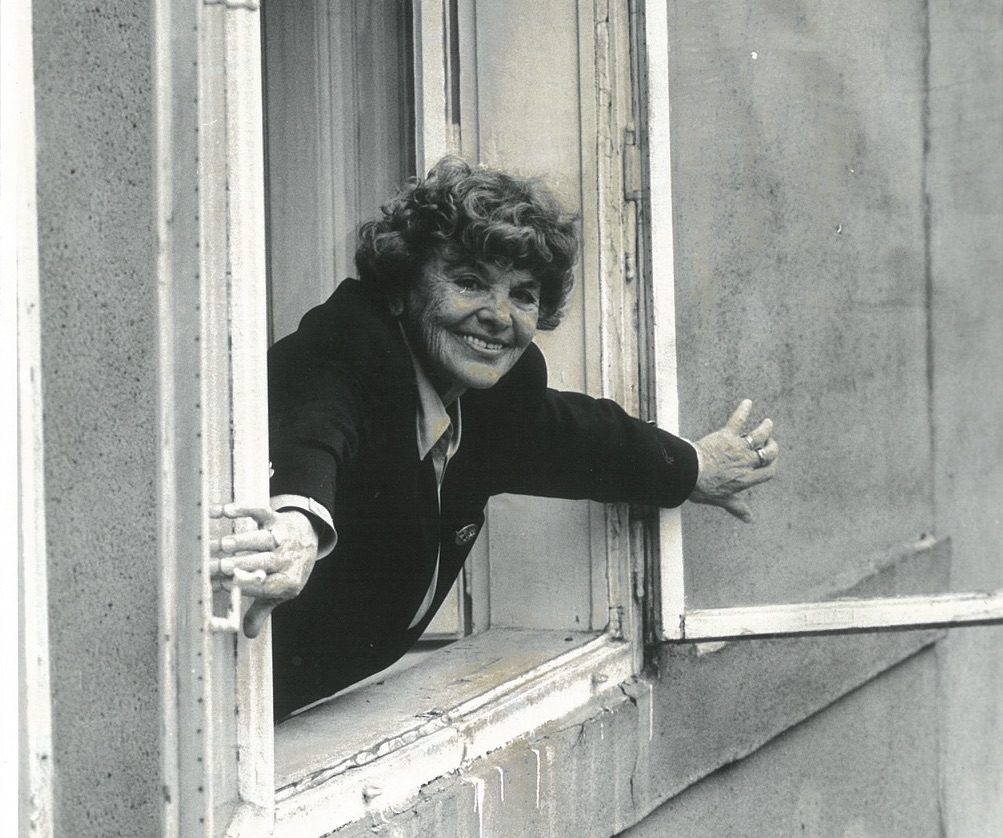

AGNEŠA KALINOVÁ (1924-2014) was a Slovak journalist and translator. Born into an assimilated Jewish family in Prešov, eastern Slovakia, she survived the war hiding in a convent in Budapest, while her parents and most of her extended family perished in the Holocaust. After the war she married the writer Ján Ladislav Kalina and moved to Bratislava, becoming a journalist. In the 1960s she was a film critic with Kultúrny život, a leading Slovak weekly that strongly supported the Prague Spring and was banned after 1968. After the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia she lost her job, suffered persecution and was briefly imprisoned before emigrating to West Germany with her family in 1978. From 1979 to 1995 she worked as a political commentator at Radio Free Europe. Her memoirs Mojich sedem životov. (My Seven Lives. A Conversation with Jana Juráňová) was published in 2012, and has since appeared in Czech, German and Hungarian translations.

JANA JURÁŇOVÁ is an acclaimed Slovak writer, playwright, essayist, translator and publisher, co-founder and editor of the feminist educational and publishing project ASPEKT. She lives in Bratislava. She has written several theatre and radio plays, children’s stories and collections of short stories including Heavenly Loves (2010) and Other People’s Stories (2016) and the novella Unfinished Business (2013). Her longer works includes the feminist crime story The Suffering of the Old Tomcat; the novel Beadswomen (2006) and Ilona. My Life with the Bard (2008, English translation 2014), as well as My Seven Lives, a memoir of the Agneša Kalinová in the form of a book-length interview. For more information see www.janajuranova.sk

____________________________________________________________________

JULIA and PETER SHERWOOD are based in London and work as freelance translators from and into a number of Central and East European languages. Julia Sherwood was born and grew up in Bratislava, Slovakia, and spent more than 20 years in the NGO sector in London before turning to freelance translation some ten years ago. She is editor-at-large for Slovakia with the online journal Asymptote. Peter Sherwood’s first translations from the Hungarian appeared fifty years ago, but he was an academic for over forty years before retiring and devoting himself more or less full-time to translating. Their joint book-length translations into English include works by Balla, Daniela Kapitáňová, Uršuľa Kovalyk, Peter Krištúfek, Pavel Vilikovský (from the Slovak), Hubert Klimko-Dobrzaniecki (Polish) and Petra Procházková (Czech). Peter’s translations from the Hungarian include works by Béla Hamvas, Noémi Szécsi, Antal Szerb, and Miklós Vámos. For more information, see juliaandpetersherwood.com

____________________________________________________________________

Read more work by Agneša Kalinová:

First excerpt from Seven Lives in B O D Y