MY SEVEN LIVES

(an excerpt)

Agneša Kalinová in conversation with Jana Juráňová

By 1939 the Slovak Republic had started to introduce repressive policies. What was its impact on your and your family’s everyday life?

The Slovak parliament in Bratislava passed a series of bills to curtail Jewish “diversionist activities”. This is all well documented so I’m not going to list every piece of legislation and will just mention that some local officials immediately went out of their way to implement it, sometimes going over the top. So, all of a sudden my father was detained for a day. A bunch of Jewish doctors and businessmen were also picked up, held for a day or two and blackmailed, mostly for cash, before they were let go. Starting in the fall of 1939 this kind of thing would happen more and more often. One night around this time Jewish shops were daubed with huge white swastikas and stars of David. And the early 1940s saw the launch of the Aryanization campaign, which had quite a significant impact on the economic structure of the city and the life of its population. What it meant was that all Jewish shops had “Aryan” that is non-Jewish managers imposed on them. Their job was to gradually get rid of the original owners, rob them of their property, taking it over. Some of the Aryanizers treated the Jewish owners more humanely, some even saved their lives later on, but others got rid of them immediately or kept blackmailing them until they had nothing left. The man who Aryanized the business belonging to the family of my best friend Marianna looked after them until the Uprising [in August 1944] and even managed to arrange an exemption for them.

Were you able to continue your education?

After I had completed the sixth grade of the 8-year gymnasium in 1940 I still enjoyed the summer holidays. There was this old swimming pool in Prešov, it had wood panelling that was quite rotted away and the water wasn’t exactly crystal clear either, but unless it was pouring with rain we’d be out there every day. The older girls would sit on the wooden terraces above the pool flirting with the boys and we would sit below, watching and gossiping about them. We had spent the whole summer of 1940 at the swimming pool and I was just beginning to grumble that school was about to start again – what a bore.

But then – it was on the 28 or 29 August 1940 – a decree was issued barring Jews from all secondary schools. Jewish children were allowed to complete compulsory primary education up to the age of fourteen, but only in specifically designated schools. On that day it made the headlines in all the newspapers. I was a sixth former, with two years to go before my matura, the school leaving examination. As I held the newspaper in my hands I broke down in tears. I suddenly felt so sad that my schooldays were over, that six exciting years of my life were over, and that the chance of getting my matura was gone. I couldn’t really believe it was possible, that it was really happening.

What did you do then and how did your parents respond?

While I was still crying my mother went into the other room. I remember that she put on her hat – in those days a lady wouldn’t be seen dead without a hat – and then went out. When she returned she told me that the next day I could be starting at Mrs. Erdős’s on the High Street as a trainee seamstress. There would also be other girls there who had just been kicked out of school. I would learn how to use a sewing machine, sew nightgowns and men’s shirts, and later on Mrs. Erdős would also teach me how to cut patterns. I agreed without protest, I was quite glad that something was going to happen, it might even be quite interesting, who knows. I’m not saying I was overjoyed but I accepted it as a solution.

What else were you prohibited from doing?

From the autumn of 1940 we were prohibited from strolling on the korzo, the main street. Jews were not allowed to show their face there in the evening. I forget how this ban was formulated but we had to observe it. So we went on to create a parallel, Jewish korzo, and would stroll up and down the left-hand side of Main Street, leading up to the church. The korzo was full of young Jewish men from all over Slovakia who’d been conscripted, but instead in the army they were sent to serve in labour battalions, some of which were deployed in Prešov. We were forced to live in a purely Jewish enclave. Sometime in late autumn 1941 a decree came out that said the Jews had to hand in their skis and skiing gear and shoes as well as their ice-skates. I didn’t care about the skates, as I grew older I didn’t think it was much fun to go around a tiny rink in circles. But having to give up skis felt like a slap in the face, a personal insult, a real loss. It meant that the Jews were no longer welcome on the few skiing slopes around Prešov. We all knew each other, you see, so I couldn’t really turn up on the slope anymore, unless I came without my skis, just to watch others going downhill and showing off. Skiing has always been my favourite sport. I just feel happy in white wintery landscape.

How did they go about confiscating your skis? Did the go from house to house?

No, a decree was issued telling us to hand them in on a certain date and in a certain place. But instead of going to the collection point, I went to my former nanny Adrienne with my skis and sticks and asked her to keep them for me. She stowed everything away in her cellar and promised to return them when it was allowed again. (And she kept her word – a few months after the war she gave me my skis back.) Then, in the spring of 1941, another decree banned Jews from living on Main Street, so in March we had to move out of my grandmother’s house where we’d lived since 1939.

Where did you move to?

The Csatáris, an old Prešov gentry family, had a summer house they didn’t use very much anymore. It was on the outskirts of town but not too far from downtown, surrounded by a beautiful park. The river Torysa flowed through it and it had a chain bridge modelled on the famous one in Budapest. It swayed nicely when you crossed it. You could also access the house by a proper road around the back where there were open fields and some Bulgarian gardeners had their plots. My parents and my grandmother rented this house together with another couple, the Bárkánys. I remember helping Mrs Bárkány dig up some perennials from her garden and schlep them to the Csatári garden where we planted them. I was happy because it seemed such a wonderful place to be moving to. It was in the spring of 1941.

A year went by, spring arrived, and in March 1942 the first deportations of Jews began. As far as I know, Slovakia was the first country apart from Germany that started to send transports directly to Poland, and as far as I know it was the only country whose government actually paid the Reich for it. Deportations started simultaneously throughout Slovakia.

I don’t think anyone in Prešov had any idea what was in store. But since it was a small town, rumours started to circulate a day or two earlier. The authorities must have received their instructions a few days in advance and the information must have leaked out. The day before the decree was actually issued, my mother, a very energetic person, went into town. I don’t know what exactly she discovered, I don’t know what information she had, but she must have learned that something would be happening to Jewish girls the next day, that they would be taken somewhere…. I don’t know how many people my mother went to see but eventually she visited her beloved nephew Ernest Neumann, an orthopaedic surgeon, whom I called Uncle Ernő. When she came back home, she said: “We’re going to see Ernő, he wants to explain something to you”. We went to see him, and he told me that if they came for me, I should pretend I had sciatica. Apparently sciatica is difficult to diagnose accurately, especially in those days it wasn’t possible. Ernő told me about two basic symptoms, neither of which can be proved or disproved.

Then came the day that the decree ordering the deportation of Jewish girls was issued. It was in all the papers and probably also posted all around town. All I know is that we didn’t receive any summons at home. But we knew that all unmarried Jewish girls and young women between the ages of 16 and 30 were to report to the courtyard of the Reform primary school that I had attended as a child. There was a big courtyard between the Reform synagogue and the school and that’s where all the girls were supposed to assemble. I didn’t go and instead stayed in bed reading Franz Werfel’s famous novel The Forty Days of Musa Dagh, [about the Armenian resistance to the Turkish genocide]. […]

After I failed to turn up at the courtyard, they came to see me. They were looking for girls who had failed to report. Most of them had gone into hiding or managed to escape. By then some girls had somehow managed to get hold of false papers and hide in a village, in other cities, or their parents had sent them illegally across the border to Hungary. A doctor was despatched to see me. He went through the whole sciatica exercise with me; I played my role and he conceded that I was sick and left. But that wasn’t enough. A few days later we were told they would take me for another check-up at the courtyard. I was carried there, as I was pretending I couldn’t stand up on my feet. I was brought to the courtyard of the Jewish school on a stretcher and in an ambulance; it was slowly getting warmer, a pale March sun was shining. I was wearing only pyjamas and was covered with a blanket. […] They carried me inside and I was examined by some doctors and in the end I wasn’t taken. I was declared unfit for work, because at that point they were still selecting girls under the pretence that they would be working. All we knew was that the girls would be going somewhere abroad with just a small suitcase. I have to say, I still admire my mother for her determination not to let me go. I think some eighty to ninety per cent of the girls had gone, because they didn’t know where they were going but mainly because neither they nor their parents had plucked up the courage to defy the decree, the order from above. I was seventeen then, almost eighteen, but when I imagine what it was like – sending girls as young as sixteen God knows where and why, “for work”… There were also rumours that they might be taking them to German brothels. My mother deserves all credit for my not being taken. She had the courage to pull it off. My father, who was otherwise a big risk taker, was rather passive in this respect. He approved her decision, he supported her, but it all depended on her. Because if she hadn’t put her foot down, I would have had to go.”

With the help of relatives Agneša was able to escape to Budapest and survived the war and the deportations of Hungarian Jews hidden in a Catholic convent and later hiding in the city. However, her parents were deported from Prešov a few months after her escape and died in Auschwitz soon afterwards; many other close and distant relatives and friends, of whom she writes movingly in the early chapters of her book, also perished.

____________________________________________________________________

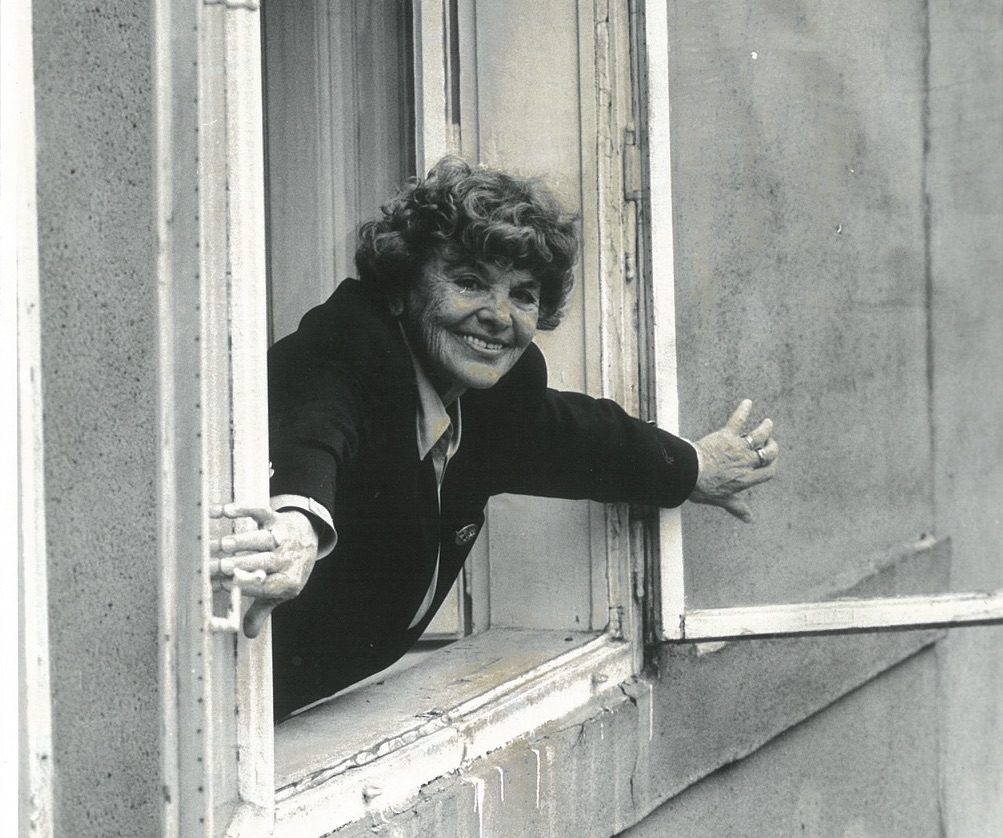

AGNEŠA KALINOVÁ (1924-2014) was a Slovak journalist and translator. Born into an assimilated Jewish family in Prešov, eastern Slovakia, she survived the war hiding in a convent in Budapest, while her parents and most of her extended family perished in the Holocaust. After the war she married the writer Ján Ladislav Kalina and moved to Bratislava, becoming a journalist. In the 1960s she was a film critic with Kultúrny život, a leading Slovak weekly that strongly supported the Prague Spring and was banned after 1968. After the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia she lost her job, suffered persecution and was briefly imprisoned before emigrating to West Germany with her family in 1978. From 1979 to 1995 she worked as a political commentator at Radio Free Europe. Her memoirs Mojich sedem životov. (My Seven Lives. A Conversation with Jana Juráňová) was published in 2012, and has since appeared in Czech, German and Hungarian translations.

JANA JURÁŇOVÁ is an acclaimed Slovak writer, playwright, essayist, translator and publisher, co-founder and editor of the feminist educational and publishing project ASPEKT. She lives in Bratislava. She has written several theatre and radio plays, children’s stories and collections of short stories including Heavenly Loves (2010) and Other People’s Stories (2016) and the novella Unfinished Business (2013). Her longer works includes the feminist crime story The Suffering of the Old Tomcat; the novel Beadswomen (2006) and Ilona. My Life with the Bard (2008, English translation 2014), as well as My Seven Lives, a memoir of the Agneša Kalinová in the form of a book-length interview. For more information see www.janajuranova.sk

____________________________________________________________________

JULIA and PETER SHERWOOD are based in London and work as freelance translators from and into a number of Central and East European languages. Julia Sherwood was born and grew up in Bratislava, Slovakia, and spent more than 20 years in the NGO sector in London before turning to freelance translation some ten years ago. She is editor-at-large for Slovakia with the online journal Asymptote. Peter Sherwood’s first translations from the Hungarian appeared fifty years ago, but he was an academic for over forty years before retiring and devoting himself more or less full-time to translating. Their joint book-length translations into English include works by Balla, Daniela Kapitáňová, Uršuľa Kovalyk, Peter Krištúfek, Pavel Vilikovský (from the Slovak), Hubert Klimko-Dobrzaniecki (Polish) and Petra Procházková (Czech). Peter’s translations from the Hungarian include works by Béla Hamvas, Noémi Szécsi, Antal Szerb, and Miklós Vámos. For more information, see juliaandpetersherwood.com