FLEETING SNOW

(an excerpt)

Fleeting Snow

Fleeting Snow

A novel by Pavel Vilikovský

Translated from the Slovak by Julia and Peter Sherwood

Published by Istros Books

5.a

Here’s the thing: it all started when I found an old photograph at the bottom of a drawer while cleaning. It was taken on our first date – actually, it wasn’t even a proper date, we weren’t quite sure at that point that it was one. Someone, probably a fellow student, snapped us sitting on a bench, caught in the act and smiling at the camera in embarrassment.

I showed my wife the photo: ‘Look!’ I thought it would make her smile, like it made me, this time not in embarrassment but rather smiling indulgently at those two silly young things. She stared at the photo for a long time; she didn’t know where her glasses were so she held it close up and scrutinized it as if scouring it for fingerprints. In vain, for the only prints on it were mine, and now also hers. Eventually she asked: ‘Who is that with you, some girlfriend of yours?’

‘Of course it is’, I said. I thought she was making a joke; after all, she recognised me without any problem, or at least guessed who I was. But she wasn’t joking, she was simply a stranger to herself. She put the photograph to one side and gave me a questioning look, as if about to say: ‘That’s the first I’ve heard about this.’

‘Yes’, I went on, ‘a girlfriend. This one here’, I said, poking her in the ribs with a finger. She picked up the photo again, looked at it for a while and shook her head in disbelief.

I just laughed it off at the time.

2.f

Although nobody has ever seen the soul, we assume that it exists. At least everyone talks about it as if the term referred to something specific and indisputable, even if it cannot be seen. After all, how many of us have ever seen atoms with our own eyes? Atoms are just a hypothesis, like the soul, and yet scientists speak of them as a proven fact. It is one of the little tricks we humans play: whenever something is beyond us, we invent a name for it, at the very least, or borrow one from some ancient language, and we feel more secure straight away.

The soul can’t be seen because it is hidden inside the body. Strangely enough, we can’t see even our own soul, we just know it’s in there somewhere. What’s even more strange is that all of it fits into our body even though we sense that it’s somehow much bigger. That it transcends the body in every way.

There are several theories of the relationship between the body and the soul. One claims that the soul is inserted into in the body as if into a case, and once the case is battered and worn out, the soul departs and moves on – where to is anyone’s guess. Maybe that Someone who placed the soul in the body to start with takes it back again. According to this theory, the soul does not wear out simultaneously with the body and even if it does, it may be recycled in hell, or purgatory, or heaven, depending on the degree of wear and tear. Another theory presumes that it is the body that produces the soul and once the body ceases to be operational, the soul too is extinguished. The soul factory closes down.

One can only theorise about the soul’s characteristics. Is each of us issued with the same soul to begin with and after that it’s up to us how we treat it and how it evolves? Or is a baby born with a harelip or congenital brain damage supplied with a soul that is different from a healthy one? And what if the soul is given once and for all and never changes, regardless of circumstances?

Be that as it may, the soul is a useful concept, one that is easy to work with. Anyone can project anything they like onto it.

1.g

The Menominee are becoming extinct both as native Americans and as human beings. In their capacity as native Americans they become extinct when they leave their reservations and join the ranks of other American or Canadian citizens. They get an education, learn a trade, start a business or get a job, becoming car mechanics, lawyers, doctors, actors or social workers. The legendary jazz musician Jack Teagarden, for example, was a native American, but if you didn’t know you would never have guessed. Sometimes he would perform with Louis Armstrong, a black man playing with a native American, but of course everyone could tell that Armstrong was black.

Štefan told me about this successful property developer in the US who was also a native American. Štefan couldn’t remember his full name and referred to him as Jeff. He read in the paper that the man had been charged with the murder of his second wife, with whom he had been embroiled in a lawsuit over their million-dollar fortune and custody of their two sons, although that is irrelevant in our context. Jeff was only half native American because his father was of Scottish extraction; this kind of mixing of blood also contributes to the extinction of native Americans in their capacity as native Americans. His parents had divorced because his mother had allegedly taken to drink and was said to have been predisposed to other native American vices, so Jeff, who had not got on well with his mother, went to live with his father, while his sisters stayed with their mother. For many years he had not acknowledged his native American heritage but he suddenly remembered it when the court was about to seize his assets, and he hid some expensive building equipment on his tribe’s reservation. The native Americans from his mother’s tribe welcomed him in their midst like a prodigal son and bestowed an Indian name on him – Withered Branch, say, or Stray Caribou – as well as some property he was entitled to as a member of the tribe. (Incidentally, Stray Caribou was not a Menominee, his mother had been a Shawnee.) But once the immediate danger passed, Jeff left the reservation and turned his back on his heritage, dying for the second time in his capacity as a native American. As a human being he might still be alive, but one day he will also die as a human being, like everyone else.

Native Americans who live on reservations could be said to be professional native Americans. This is not a demanding job, as they have received generous government subsidies in com- pensation for their lost territories and hunting grounds. Still, it is hard to be a native American if you can’t behave like one. The life of present-day native Americans bears no resemblance to that of their ancestors. They no longer hunt animals for food or fur to keep out the cold; in fact there are no wild animals left on the reservations and even if there were, they would be scared off by the roar of the motorbikes as the natives race through the woods. When they feel hungry they buy their meat – deboned and pre-carved – in a supermarket or, what’s even simpler, grab a hamburger in the nearest fast food joint. And as for fur coats or thick quilted jackets, they can choose anything they fancy from a department store. The women no longer harvest crops for nourishment, nor do they sew clothes from leather, except as souvenirs for tourists if they feel like it. It is a comfortable way of life but as time goes by many realise that something is missing. They might use a different term for this void. We call it meaning or purpose.

The purpose of life is to be lived. From a personal point of view this is quite a good purpose especially since, if you want to survive, you have little time left to ponder the purpose of life. But human beings seem to be designed in such a way that as soon as they have a free moment they start wondering about silly things, for example why they came into this world in the first place and what their mission in life is. Native Americans are no exception and as they have plenty of time on their hands and the questions keep haunting them, they keep them at bay with alcohol and drugs; as they are unable to find any answers, they prefer to forget the questions. They could seek advice from their council of elders, provided such a thing still exists on their reservation, but their elders grew up in very different circumstances and their advice would be of little use to the young. And so the native Americans living on reservations remain native Americans for the rest of their lives but they become extinct as human beings, with their health ruined and tormented to death by the void.

Admittedly, all I know about native Americans is what I picked up from trashy Westerns, set in an era when they had not yet been driven onto reservations, or from Štefan, who has never set foot in an Indian reservation. He hasn’t even learned the Menominee language. There would be no point since there is no one he could chat with. He just learned individual words, primarily those containing bilabial consonants, but without understanding their meaning. He didn’t need to learn the language. Based on his study of the phonetics of their language he concluded that the Menominee had once been a particularly fearless and ferocious tribe. But that was a long time ago, before the avalanche.

____________________________________________________________________

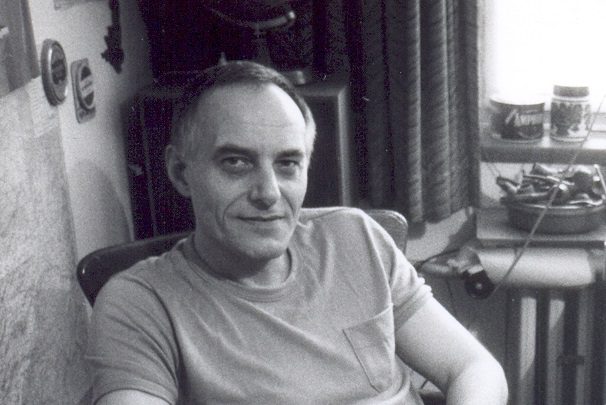

PAVEL VILIKOVSKÝ was born 27 June 1941 in Palúdzka. He studied to be a film director at FAMU in Prague, changing courses after two years to study English and Slovak and graduating from Comenius University, Bratislava in 1965. He worked as an editor at the publishing house Tatran, and from 1976 to 1995 as a deputy chief editor of the literary monthly Romboid. He has also worked in the Slovak editorial department of Reader’s Digest. Hailed as one of the most important Central European writers of the post-Communist era, Pavel Vilikovský actually began his career in 1965, but the political content of his writing and its straightforward treatment of such taboo topics as bisexuality kept him from publishing until after the Velvet Revolution. In 1997 Vilikovský won the Vilenica Award for Central European literature. A book of Vilikovský’s collected prose Evergreen Is… was published in an English translation by Charles Sabatos in 2001.

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translators:

JULIA and PETER SHERWOOD are based in London and work as freelance translators from and into a number of Central and East European languages. Julia Sherwood was born and grew up in Bratislava, Slovakia, and spent more than 20 years in the NGO sector in London before turning to freelance translation some ten years ago. She is editor-at-large for Slovakia with the online journal Asymptote. Peter Sherwood’s first translations from the Hungarian appeared fifty years ago, but he was an academic for over forty years before retiring and devoting himself more or less full-time to translating. Their joint book-length translations into English include works by Balla, Daniela Kapitáňová, Uršuľa Kovalyk, Peter Krištúfek (from the Slovak), Hubert Klimko-Dobrzaniecki (Polish) and Petra Procházková (Czech). Peter’s translations from the Hungarian include works by Béla Hamvas, Noémi Szécsi, Antal Szerb, and Miklós Vámos. For more information, see juliaandpetersherwood.com

____________________________________________________________________