APHORISMS, ANECDOTES, AND OTHER LITERARY TRIFLES

Excessive pessimism is just as repugnant as excessive optimism: two identical idiots dressed in a different color – one black, the other pink.

***

Bourgeois wisdom consists in this: that life must be spent with one wife, but lovers may be occasionally traded.

***

Government is like a bothersome fly, buzzing. Buzzing, buzzing in your ear. It then lands and proceeds to bite you like a dog. God have mercy!

***

In this world, there are quite a few women who adamantly love dogs, cats, birds in cages, but not people. There are such men as well, but fortunately these are not many.

***

In old age, you almost cease to feel spring, summer, fall, winter, and only sense: warm, cold, wet, windy.

What boredom!

***

This is what good writers do: they take living people and plant them firmly in their books. Those people extract themselves from the books and reenter life, but already somehow transformed, I would say, less mortal.

***

One must be an animal not to have considered suicide at least once in your life.

It seems to me that this is my own original idea on the subject. But perhaps it is not.

***

A woman forgets even the name of her beloved (if these were generous in number). But she most definitely remembers in minuscule detail all the dresses she had ever worn since about age twelve.

***

Goethe wrote that poetry has the greatest effect at the beginning of a cultural era, when it is still at its most unrefined and roughest.

Precisely so!

***

Reynolds:

“A crass and tiresome display of simplicity is just as unpleasant and repugnant as every other breed of inauthenticity.”

It would be beneficial for our writers to learn this lesson.

***

What a depressing rule of thumb – a scoundrel, a miscreant, a traitor, a bad seed, a foul-tempered, cowardly person – is smart, always smart! But among the goody two-shoes, the dear and kind ones – you won’t find a smarty-pants even if you search for one with a fine-tooth comb. The rarest of rarities.

***

Philosophers have always preferred to remain bachelors: Kant, Spinoza, Descartes, Leibniz.

I do not envy them. Choosing a mate requires foresight. It is substantially more complicated then writing a Critique of Pure Reason.

***

Petrarch, as is well known, extolled Laura for twenty and one years. And all that time, she kept giving birth for her own husband, some man of Avignon. She had eleven of them. This is a simple and clear thing to us. No matter what else, Petrarch is our brother in the poetic trade. What he needed, of course, was a theme; and not at all a woman. There were women enough without Laura, who, as God had intended, would become pregnant by him. When Laura died (from the bubonic plague), Petrarch continued dedicating sonnets to her.

A theme is immortal!

***

For some unknown reason, the reception for Mao Tse Tung was held not at the Georgievsky pavilion, in the Kremlin, but at the Hotel Metropole. Mao, with his retinue, and Stalin, with his “comrades in arms,” were being attended to in the Small Hall, next to the Large Hall, and all those invariably invited to attend government functions were eating and drinking their fill at the long table. The doors connecting the Small Hall to the Large Hall remained open. – The children’s poet Sergei Mikhalkov [pere], with persistence and excitement, was promenading on his very long legs across the entrance to the Small Hall, so that they would “all notice him there”. Finally, Stalin calls him over with his stubby little finger, bent at the joint. – Welcome to our table, welcome; will you please join us. And then he presents him to the Chinamen: – Our famous children’s poet Sergei Mikhalkov. Then he says something to him, then flashes him a smile, in response to one of his zingers. Suddenly, Mikhalkov sees an unfinished cheburek on the generalissimo’s plate. — Iosif Vissarionovich, I have a tremendous favor to ask of you— desperately stuttering, the artful Soviet courtier. — Which? Knowing perfectly well that Stalin likes the stuttering — it amuses him — Mikhalkov starts to stutter three times worse then he does in real life. — P..p…please, Iosif Vissarionovich, as a keepsake, would you give me your cheburek? — What cheburek? And Mikhalkov directs his excited gaze at Stalin’s greasy, smeared plate. — А?..This one? — Yes, Iosif Vissarionovich, that one! — Please, take it. It’s yours. — And so, our favorite of the Muses worshipfully wraps Stalin’s leftover into a virgin white handkerchief, profusely dripping with sheep fat.

***

In the nineteenth year of the revolution, Stalin got the idea (let’s call it that) to organize a “purge” in Leningrad. He came up with a method that seemed subtle to him: renewal of passports. And so, tens of thousands of people, primary among them the former nobility, began being refused these. These nobles had long ago become transformed into conscientious Soviet civil servants, all of them carrying cheap pig-skin briefcases. The consequence of a refusal of issuance of a new passport was immediate deportation: either close-by the tundra or to the burning hot sands of the Karakum.

Leningrad was in tears.

Not long before this, Shostakovich had been allocated a new apartment. It was some three times larger than his previous one on Marat Street. You’re not going to let an apartment stand empty and naked. So, Shostakovich scraped together some money and brought it to Sofia Vasilievna and said:

“Please, mother, buy us some furniture, won’t you.”

And he left to take care of his affairs in Moscow, where he spent some two weeks. When he returned to their new place, he couldn’t believe his eyes: the rooms now had mahogany chairs from the times of Paul and Alexander the Firsts, little tables, a wardrobe, and a desk, a quantity almost sufficient to fill them.

“Mother, you bought all this with the pennies I had left you?”

“You see, the cost of furniture just now plummeted in town,” Sofia Vasilievna replied.

“Why is that?”

“The nobility are being sent off into internal exile. Well, being in a hurry, they were giving away their belongings almost for free. So, let’s say, this desk here had cost this much before….”

And Sofia Vasilievna launched into an explanation, how much such and such thing was worth before, and how much people were paying for it now.

Dmitry Dmitrevich’s complection grew pale and his pencil-thin lips pursed even tighter.

“Good Lord!”

And, having hastily removed a notebook from his pocket, he picked up a pencil from the desk.

“How much did these chairs cost before the misfortune, mother? And how much did you pay for them now? Where did you buy them? And this desk? And the couch?” Etc., etc.

Sofia Vasilievna replied in detail, without fully understanding the reason he was asking her for all these details.

Having written everything down in his sharp-edged, scrawny, staggered handwriting, Dmitry Dmitrevich nervously tore the page out of his little notebook and, handing it to his mother, said:

“I’m going off now to rustle up some funds. If need be, from under the ground. And tomorrow morning, mother, you will deliver the money to all these addresses. All these people still have friends and relatives in Leningrad. They will send it on — to where it is needed… These chairs had cost a thousand and a half, and you bought them for four hundred — so return a thousand one hundred… And the desk, and the couch also… And all the rest… People have suffered a misfortune, mother, how can we possibly take advantage of that? Isn’t that right, mother?”

“Of course, I did everything as Mitya said,” Sofia Vasilievna told me later.

“I don’t doubt it.”

What could this thing mean?

Most likely, simple common decency. And yet, how rare it is in our lives, this simple common decency!

***

A fragile ego is a torturous, irredeemable, and irremediable, quality for a writer. And yet, oh so common.

***

Of all things, I am most likely an epicurean.

“Death has no bearing on us,” Epicurus had said, “For when we exist, death is not yet present, and when death is present, then we no longer exist.”

And that is, roughly speaking, also my attitude toward “non-existence” (to use the euphemistic philosophical term). But, when a dearly beloved being — a very dear, and much beloved one — dies, I am made entirely powerless, and then any and all clever or smug expression of succor evokes in me a reaction of rage and fury.

____________________________________________________________________

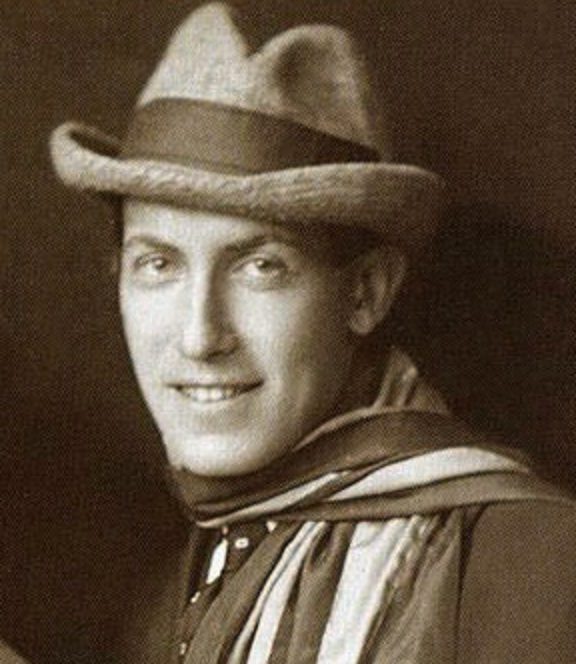

ANATOLY MARIENGOF (1897-1962) was a younger poet of the Silver Age generation of Russian Modernism and, along with his close friend Sergei Esenin, a guiding spirit of the Imaginist movement. His first work of “fiction,” Novel Without Lies (1926,) documented his relationship with the gigantically talented and self-destructive Esenin. In addition to his deliciously corrupting dose of cynicism and his impressive and early use of the modernist technique of montage, the cutting and splicing of short “set piece” fragments with documentary records, inspired by the cinematic “newsreel” methods of Dziga Vertov, characteristic of his work are the extremes to which Mariengof pushed metaphor. Following the publication in Berlin of The Cynics (1928) and The Shaved Man (1930,) for the rest of his life Mariengof was reduced to occasional writings for Soviet film, theater and radio, and Esenin’s dedications of poems to him were air-brushed from the literary record.

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

ALEX CIGALE’s first full book, Russian Absurd: Daniil Kharms, Selected Writings, came out in the Northwestern University Press World Classics series in 2017. In 2015, he was awarded an NEA Fellowship in Literary Translation for his work on the poet of “the St. Petersburg philological school”, Mikhail Eremin. His own poems in English have appeared in The Colorado Review, The Common Online, and The Literary Review, and translations of classic and contemporary Russian poetry in Harvard Review Online, The Hopkins Review, B O D Y, Kenyon Review Online, Modern Poetry in Translation, New England Review, TriQuarterly, Two Lines, Words Without Borders, and World Literature in Translation. He recently edited the Russian issues of the Atlanta Review and Trafika Europe, and is currently a Lecturer in Russian Literature and Language at CUNY-Queens College.

____________________________________________________________________