Red: The History of a Color

Red: The History of a Color

By Michel Pastoureau

Translated from the French by Jody Gladding

Princeton University Press

216 pages

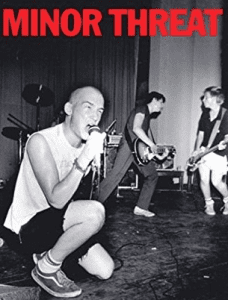

When Ian MacKaye of the seminal hardcore band Minor Threat sang “Seeing Red” in 1981, he was perhaps unwittingly engaging in a history of the color that stretches back millennia. Studying the development of specific colors and our changing relationships with them has been the life’s work of Michel Pastoureau, a French professor of medieval history and symbology. His previous books on the topic have covered blue, black, and green. All are surprisingly riveting and revealing.

Red: The History of a Color is organized into four chronological sections, examining the way human perceptions of red have changed throughout history. “The First Color” covers “Earliest Times” to the end of Antiquity. “The Favorite Color” takes us from the sixth to the fourteenth century. “A Controversial Color” examines the fourteenth to the seventeenth centuries. Finally, “A Dangerous Color?” takes us from the eighteenth century until today. Along the way, Pastoureau presents a clearly delineated argument about the way that red has come to symbolize everything from blood to divinity and anger.

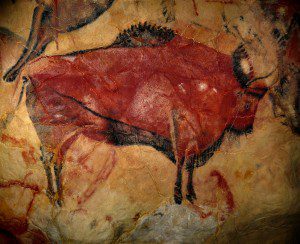

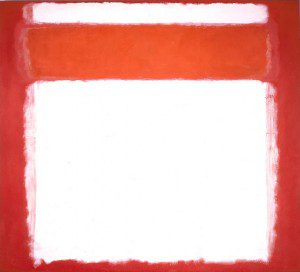

This book, like others in the series, has been handsomely designed, with color reproductions illustrating Pastoureau’s narrative. The combination of the author’s philosophical and historical insight with these sumptuous images makes for rich reading. The earliest reproduction is one of the Great Red Bison of Altamira, which were painted in the Cave of Altamira in northern Spain sometime between 15,500 and 13,500 BCE. The most recent illustration is a Mark Rothko painting, No. 16 (Red, White and Brown), from 1957. The sense of variation and development between these two images conveys the impressive scope of the study.

It’s easy to imagine colors as something fixed and unchanging, so to read about the way that different societies and cultures have regarded color in different – and often opposing – ways is fascinating. Behind this basic thesis is Pastoureau’s claim that modern societies don’t see images and colors the same way that primitive societies did. We are so overloaded with colors and images in modern life that we have become unable to untether colors from their associations and so to see them as they “are.” Discussing early cave paintings, Pastoureau writes:

Electric lighting is not the same as torch light (it goes without saying). But how many specialists bear that in mind when studying the cave paintings? And simply among visitors, who is really aware that between these paintings and the present, millions – billions? – of color images from all eras have intervened, images that neither our gaze nor our memory has been spared? These images have the effect of a distorting filter; we have consumed, digested, and recorded them in a kind of collective unconscious. … That is why we cannot see and will never be able to see as our distant ancestors did. This applies to forms and is even more true of colors.

While Pastoureau’s subject is ostensibly the color red, he, like John Berger, is actually more concerned with how we see things, color included.

What is unchanging in the history of red is its close association with fire and blood. The color has elemental and physical qualities which give it a nearly animated force. This was true for sacrificial processions in ancient Athens, and is true for the red power ties of today. Of course, red wine has long played an important role in religious practices, and here Pastoureau brings up the interesting if obvious (though overlooked) fact that red wine is not actually red, but was rather “associated symbolically with red.”

In the same way, those we consider “redheads” don’t actually have “red” hair. Nonetheless, Pastoureau writes, in ancient Rome:

Red hair had a bad reputation. For a woman, it was a sign of a wicked lifestyle; for a man, it was ridiculous and a sign of Germanic ancestry. In fact, in Roman theater, the German barbarian is a caricature, gigantic…obese…curly-haired…red-faced, and redheaded. Moreover, in everyday life, calling a man a rufus [meaning redheaded] was one of the most common insults and would remain so in clerical circles throughout a good part of the Middle Ages.

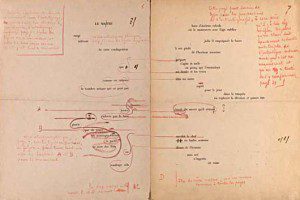

One of the surprises in the book is a manuscript page from Stéphane Mallarmé’s Un Coup de Dés Jamais N’Abolira Le Hasard (A Roll of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance), criss-crossed with notes and emendations in red. According to Pastoureau: “The very elaborate page layout and variations in type that the author desired required that six successive sets of proofs be made, all corrected with a red pencil. The poet’s key work, this unusual poem is not crystal clear.”

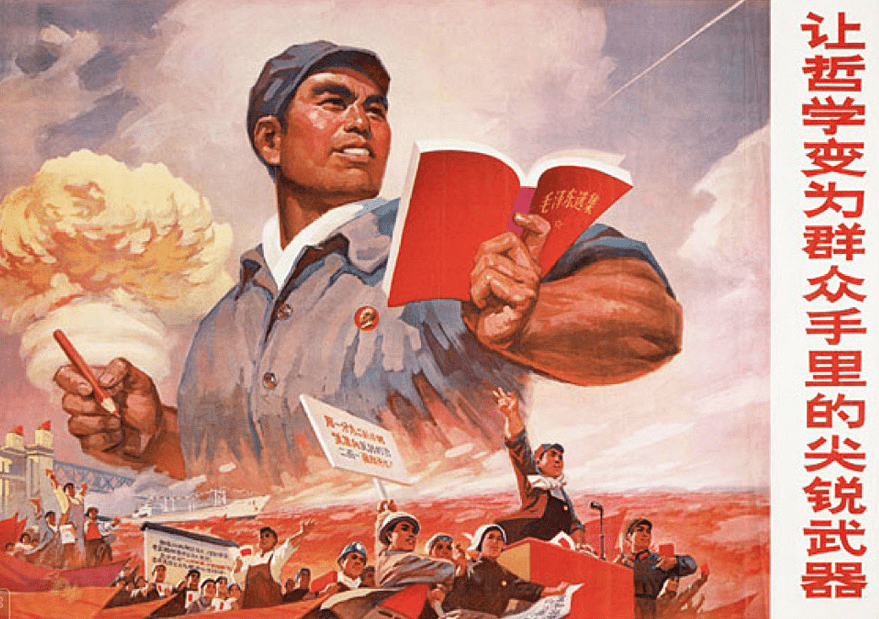

Red is a contradictory color. It is at once the color of revolution and the color of censure and correction. It is a powerful color, one that is central to religion, mythology, politics, and nationalism. Consider for a moment how many flags around the world include the color red. Pastoureau’s description of the development of our associations with red is revealing, both of the color and ourselves.

—Stephan Delbos