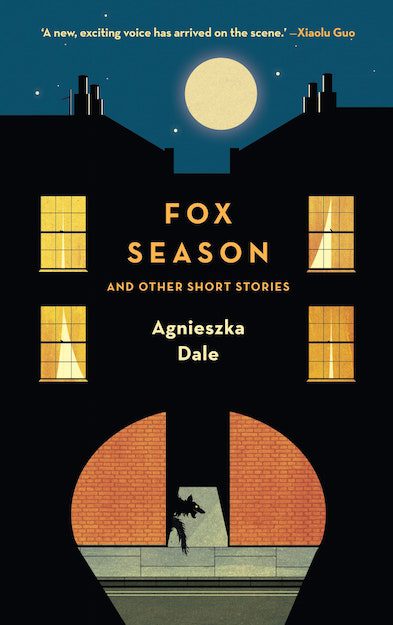

FOX SEASON

Fox Season and Other Short Stories

Short Stories by Agnieszka Dale

Published by Jantar Publishing

Permission to Bow

Like all great Polish writers, Jakub lives in the South of France, in a villa, drinking Chardonnay and speaking French to his wife. In the morning, his wife brings him coffee, says a polite bonjour, and bows. Jakub keeps on writing. He doesn’t notice the coffee until it gets cold.

Jakub doesn’t suffer from writer’s block or blocks of any kind. It’s because writing for him is pleasure, like sex with his French wife. He can’t get enough of it. Sometimes Jakub writes before this pleasure or after. Sometimes he writes right in the middle of this pleasure. In fact, his best ideas come while enjoying his wife, and typing.They have a lot of special pleasure together. Often, his wife initiates it. She comes to his room and says hey-hey. She bows. She unzips his trousers. Often, he doesn’t notice what she’s doing until it’s almost too late.

“Shall I continue?” asks his wife.

He starts typing faster and faster and she doesn’t stop. Often, his best sentences are created that way.

Jakub writes many great short stories that way, too, and many novels. He suspects all great Polish writers living in the South of France do the same thing but they just don’t tell anyone how they achieve their success.

Like many great Polish writers living in the South of France, Jakub is now very happy though he wasn’t always happy in the past. This French wife is his second wife. His first wife was French, too, but she refused to tiptoe around him and pleasure him while he wrote.

“Did your wife like to make love—to you—while pregnant?” his second wife often asks about his first wife.

“No, she didn’t,” he says. It makes him sad. A little sad. He doesn’t know why, exactly.

Then he thinks about his first wife again. She didn’t make love to him then, no, not very much. Not when pregnant. She didn’t like to be touched, maybe. Her beautiful body was pregnant with babies but she didn’t want to share the pleasure of having them inside her, like a little secret, or an untold story. Not that pleasuring was ever important to Jakub. He just wrote. He wrote when his first wife loved him, and he wrote when she stopped.

His second wife was married before, too. This is her second try, a more successful match, Jakub hopes. A match from heaven, through hell, it feels like, to him, every day. This is due to the fact that Jakub is now a wise man and he knows how to please his wife—he knows her so well, it seems. He is now able to rewrite her past for her own advantage, or this is what he is trying to do, to make this marriage work.

“Tell me a secret, another secret, or the same one you told me about yesterday, but again,” he asks his wife, every day.

“I am trying to remember,” she tells him. “I have to think about it. I need time to think.”

“Take your time,” he says but he can’t wait, he just can’t wait. He likes when his wife talks. He just closes his eyes and listens to her. She is full of secrets. There are things about her he doesn’t understand. And when she talks, he asks her: Why? He asks it a lot.

For a start, why does she bow? It does feel strange sometimes, her bowing so much to him. Though Jakub is Polish and his wife is French, he lets her bow. It feels as if he allowed it. It feels, actually, as if she had asked. He gives her this permission—he thinks it’s a permission—because he knows her darkest secrets, but not all of them. He is beginning to find out about her secrets, more and more. He is hoping that the more he learns about his wife, the more he can help her to be happy. Because the past will not just disappear, he is realising this now. He can’t just delete it like a bad sentence; burn a bad novel. It doesn’t work like that.

Like many great Polish writers living in the South of France, in a villa, drinking Chardonnay and speaking French to his wife; a wife that bows, continuously; bows in French; bows dressed; bows naked; bows with coffee and without, Jakub often asks his wife about her past, and why her first marriage broke down. Instead, she tells him about her five older brothers and what it was like to be locked in with them for five days, in a room, while their parents observed them through a little keyhole, in the French countryside, somewhere in Normandy, a long time ago. Jakub loves this story, as any great Polish writer would, of course, and he likes being told and re-told this story by his second French wife.

“This is not a story of abuse per se but rather great love and experimentation, and life really,” he tells his wife.

“Yes,” says his wife. “Things happen, in life.” She nods. Or is it a little bow?

“Your parents of course were not nice,” says Jakub. “ They were simple, very cruel, and rather crude French farmers. But you coped. You found pleasure.”

“I never thought of it like that,” says his second wife.

Jakub asks about this story every day and he is rewriting the beginning every day, too. It’s the most difficult story he has ever written, he thinks. It’s because he is worried how he should tell it to his wife. This is a good story, he is thinking, and it sometimes goes like this: Jakub’s second French wife is locked in with her five brothers, for a long five days, at the sweet age of sixteen and of course she ends up bowing to them. But why? Why did this happen, in real life? Maybe she was stronger than her brothers. Maybe. Maybe not. Maybe she also coped much better with being locked in the same room. Maybe not. Maybe her five brothers just needed her support—or just something to do—while they waited for the doors to open. Maybe not.

When Jakub asks his wife what her brothers asked her to do, she tells him a different story every time. Sometimes she just talks about one of the brothers kissing her on the lips while the rest watched, waiting for their turn. Other times, she says she wasn’t kissed on the lips but somewhere else.

“But where? Where did they kiss you?”

As a response, she only smiles, or cries. But smiles more often than she cries. Few tears, no sobs. Often, she talks about the kisses leading to something else, which she can’t remember, not that day. She does, however, remember her parents taking her to the local abortion clinic. There are days when she says this happened much later, and not that very day, month, year.

When his wife tells him the story, Jakub tries not to imagine the parents looking through the keyhole, though he sometimes can’t help thinking that by asking his wife to retell this story again and again—by obsessing about it so much—he is now looking at her though a little keyhole and imagining her as a sweet sixteen-year old girl, and bowing to her brothers, and whatever happened next. Sometimes Jakub sees himself as her brother, and he is so gentle to her. Sometimes he is another brother, not so gentle.

Like all great Polish writers living in the South of France and drinking good wine with their good French wives, who bow and bow, Jakub thinks his wife might be deceiving him. He is worried that when she says she is meeting her friends in Paris, every spring, around Eastertime, she in fact goes to visit her brothers in a little village in Normandy, again and again. Her parents are there too, now very elderly but still cruel and controlling.They lock her in the same room for a few days and watch their six children—now adults in their forties—through the little keyhole maybe, again and again. They are so old they can’t see much but they can hear something, surely.

Like all great Polish writers living in the South of France with a wife who is such a great mystery, like a book he is reading and reading, Jakub realises—more and more often—that he doesn’t understand why his wife needs his permission to bow, and doesn’t just bow if she wants to. He often wonders if it has anything to do with her thinking that bowing is inappropriate. In fact, maybe her bowing is something unnatural to her. Does she not feel adequate? After all, man and woman are equal and they don’t need to bow, not really.

Every time Jakub thinks of bowing, just bowing, anyone bowing—not just his wife—he realises this is not something he remembers from his childhood. Bowing was not how women behaved around him. His sisters didn’t bow. His parents didn’t bow. Nobody bowed. Bowing was not part of his upbringing.

Women he knew were not always strong but neither did they bow. Even weak, frail, dying old women refused to bow. Even dogs didn’t bow. Trees didn’t bow. Nobody bowed.

He doesn’t understand why his wife asks him for permission. Why every time she wants to bow, she asks: May I? She then bows so low that her nose almost touches the floor. In fact, sometimes her nose does touch the floor. If not the floor, then the zip of his trousers.

Like all great Polish writers living in the South of France with a wife who bows, just bows, and does it so beautifully that it is almost painful, Jakub realises—more and more often—that he doesn’t know if he can or can’t live without his wife, and her bowing. If his wife left him today, or tomorrow, would his writing suffer, or not at all? Would he get very depressed and commit suicide, or would he not? More importantly, would he write? Write better? Not write at all?

Jakub doesn’t want his wife to go, of course. Nor does he want to be depressed or to commit suicide. But he is curious. If—one day—he didn’t give his wife permission to bow, how would it affect his writing, and her?

So one day he tells her not to bow. In fact, he prohibits bowing.

At first, she doesn’t obey. She keeps on bowing.

“Don’t bow. I just want to see what happens if you don’t bow. I just want to understand why bowing is so important to you; to me.”

“Non,” she says. “Never. Because I love you so.”

Day after day, he begs her to stop bowing, until one day he dares her:

“Stop bowing, if you love me. Just for a day. One day. Please.”

“So it’s just a test?” She trusts him, it seems, day after day,

more and more, but still she bows. So maybe she doesn’t trust him. Not completely.

Then one day she says: “I want to stop, for you, but only because I am realising that ceasing all my bowing is in itself a sign of bowing. Not bowing is bowing more; and deeper, with more affection.”

“Do you know how great you are?” he asks his wife. He asks her this question a lot. She just bows and says a quiet “thank you.”

When she finally stops, which is both great and strange, it doesn’t seem to affect his writing at all. Like all great Polish writers living in the South of France with a wife who bows, or doesn’t bow, Jakub just keeps on writing, better than before, or perhaps just as well. There is no change. His wife, however, seems a little lost. Then—very unhappy. In fact, she looks more and more unhappy every day. So unhappy that Jakub is worried about her, more and more.

“What is the matter, my love?” He asks her, day after day.

She bursts into tears, every time he asks.

Slowly, she is beginning to talk. A little. A little every day, he hopes. Maybe more. Soon more.

She is remembering her childhood, she says, and her bowing with her brothers; to her brothers; for her brothers. Jakub asks her to tell him the exact story, every day, but she refuses. Every day, she remembers more and more, she says, but she seems to be saying less and less.

“Please,” she asks him, again and again. “Just let me bow to you. Let me bow. I can’t tell you. But I can show you maybe.”

Like all great Polish writers living in the South of France, Jakub now permits bowing because the lack of it seemed to be killing his wife. He is now aware—more and more aware, every day—of the simple fact that his wife bows to him like she bowed before. It doesn’t affect his writing—he can still write with or without his wife’s bowing—but it affects what he is writing about. Not how though. Or why. Well, maybe a little.

At night, when he stops writing, he often reads his work to his wife. Or he is beginning to.

The story often describes two great Polish writers. The first writer in the story is a writer who has a lot of new ideas, a new idea every minute but can’t carry on with any of them. Before he settles into one idea, another, better idea comes to his head and he gets distracted. The second writer has many good ideas too, but not as often. He is a bit slower than the first writer. But he can see logic between the ideas of the first great writer. Sometimes the logic is about removing one idea, somewhere in the story, and the story suddenly becomes great. The first writer is grateful for this, and bows.

“I didn’t see how this idea is unnecessary,” he says to the second great Polish writer. “But I still can’t delete it. I find it hard to delete.”

“Maybe don’t delete it but use it in another story,” says the second great writer. The first great Polish writer then bows to the second great Polish writer, thanking him for removing something from his story, or inserting into another.

“Do you know how great you are?” the first great Polish writer asks the second great Polish writer, and really means it.

Jakub reads this story to his wife before bed. Every night, he then places his wife on top of five soft pillows and bows to her. The wife asks him to stop this, every night. She gets angry. She tells him that if he doesn’t stop, she will kill herself, and him, every night. Often, she leaves the bedroom, slamming the doors.

Again, Jakub doesn’t want his wife to go, or be depressed or commit suicide, or kill him, or slam the doors. So he is now working on another story. It’s still a story of his wife bowing to her brothers though he is rewriting it from his earlier versions. Slowly, the story is beginning to say this: A whore, a great powerful whore, is born in the French countryside. She seduces her five older brothers, and even her elderly parents. She uses sex as a powerful tool to get what she wants: attention from parents, and love from her brothers. Nobody can resist her. Not even animals, or insects. Everybody loves her, everybody wants her. Jakub reads this story to his wife before bed. After, he places his wife on top of the five pillows, and again, as every night, he tries to bow. He even asks her permission now:

“Can I bow, please?”

“You know what I am going to say,” says his wife, every day, but with less and less conviction maybe. Is she not sure?

Lately, he is beginning to bow to her, a little, just a little, with his head, like an almost imperceptible nod. And she is beginning to like it a little, it seems, a little more. She even smiles a little now. A little more than the night before. More and more. Little by little.

____________________________________________________________________

AGNIESZKA DALE (née Surażyńska) is a Polish-born London-based author conceived in Chile. Her short stories, feature articles, poems and song lyrics were selected for Tales of the Decongested, The Fine Line Short Story Collection, Liars’ League London, BBC Radio 4, BBC Radio 3’s In Tune Live from Tate Modern, and the Stylist website. In 2013 she was awarded the Arts Council England TLC Free Reads Award. Her story “The Afterlife of Trees” was shortlisted for the 2014 Carve Magazine Esoteric Short Story Contest and longlisted for the Fish Short Story Prize 2014.