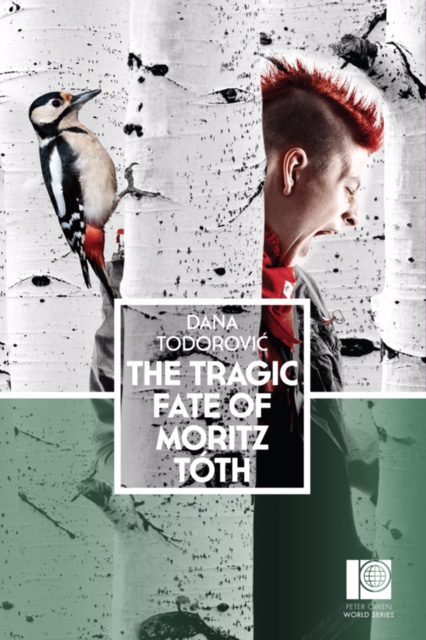

THE TRAGIC FATE OF MORITZ TOTH

(an excerpt)

The Tragic Fate of Moritz Toth

A novel by Dana Todorović

Translated from the Serbian by the author

Published by Istros Books

The first time I met Noémi was at Zichy Square on my way home from a medical examination. I recall Dr Horvát – safely hidden behind the impenetrable wall of false concern and the thick lenses of her glasses – informing me about a dramatic 15 per cent loss in body weight since she had last examined me. She asked me if I had been drinking and if I had been following the nutritional regimen she had prescribed, and I responded that, of course, I had not been drinking and, of course, I had been following the regimen with rigorous discipline. Needless to say, it was a bold-faced lie if there ever was one. The truth of the matter was that in the months preceding the examination my life had become drained of all meaning and seemed to be disintegrating in slow motion before my very eyes. I had also managed to acquire a collection of chronic illnesses with dubious characteristics, such as irritable bowel syndrome and non-specific tachycardia. Furthermore, despite all the therapy I was receiving, I still needed my liquor like a newborn needs its mother’s milk, and had Dr Horvát been the least bit concerned about my health, instead of merely eager to ease her duplicitous health-practitioner’s conscience, she would have noticed that my eyes were nearly falling out of their sockets that morning from vomiting and that my stomach was the size of a watermelon; had she been the least bit concerned, she would have eventually sensed my desperate need for attention, understanding and close human contact, just as Noémi sensed my condition later that day at Zichy Square.

She was standing with two other scantily clad women in the middle of the square, looking my way, and I immediately understood the motive behind her interest. In an attempt to circummnavigate them, I started to cross the street outside the pedestrian crossing, only to be knocked over by a Harley that came flying around the corner, instantly making me land nose first on the pavement. The thick folder I was carrying was propelled to the other side of the street; medical reports, referrals and X-rays took off left and right – my liver in one direction, a kidney in another … Then this scantily clad but genial girl approached me and kindly helped me collect all my scattered body parts. While discretely inspecting the documents as she gathered them off the pavement, she commented that as far as she could tell it would take a miracle to get me out of the mess I was in. I gave a witty reply about how a new nose and a good beating would do just fine for the moment, which, in hindsight, appears to have been quite an astute observation.

I was lucky enough to end up without any serious injuries – only with some rather profuse bleeding. The young woman who helped me collect my documents suggested we go to her house so that she could disinfect my wounds. She said that she lived just around the corner and that her name was Noémi. I took her up on the offer, mainly because I had little option.

She did indeed live around the corner, right off the square on Naspolya Street, near the kiosk with Csaba’s legendary breaded chicken wings. The building had no lift, so we had to climb up the stairs to the third floor. On the landing between the first and second floors we passed a colossal creature in a long black coat buttoned up to the neck who contemptuously measured us from head to foot. Noémi whispered that the creature’s name was Ilka and that she was commonly known as Ilka the Minotaur and advised me not to take her scornful grimaces to heart. Upon entering the flat, she led me through the narrow hallway and into the living-room and left me sitting on the sofa while she went to fetch the supplies necessary for the forthcoming procedure. The room seemed to be covered with a sheen of cleanliness and smelled like a bouquet of wild flowers, making me feel like a withered weed by comparison. When Noémi returned with an eager expression on her face and a huge cardboard box overflowing with medical supplies, I suddenly felt like I had not travelled that far from Dr Horvát’s office. She sat beside me and rummaged through the box, which was when I noticed that the collection of documents revealing my state of health was lying open for inspection on the table in front of us. I caught her gaze sweeping over it a few times, and that finally gave me the incentive to share with her my sad story.

I told her about Juliska, my great love and later my great loss. I told her about Juliska’s unconventional upbringing, about her father the military envoy who dragged her and her sister from one private school to the next in faraway locations such as China and Indonesia. I also told her about something that was very difficult for me to share with anyone, especially with Dr Horvát and her psychiatric team; I relayed to her the details of the fierce argument that had broken out on the day of the funeral between Juliska’s father and me in front of their most intimate family circle – he had blamed me for his daughter’s demise, saying that had she not met a bum like me she would never have been driving her new Lexus through that run-down industrial quarter in the dead of night.

Noémi listened with a compassionate expression on her face, occasionally nodding her head in understanding. However, what I did not know as I sat there watching her tend to my wounds was that while patiently allowing me to lift the blackness from my heart for one afternoon she had in mind an entirely different form of therapy, a dose of which I was to receive from her several times a week in the course of the following two months for the considerable sum of seven and a half thousand forints per hour.

After I returned home from Noémi’s on that ill-fated morning when I desperately tried to evade the grotesque creature that I later adorned with the nickname ‘the Birdman’, I was greeted by a deadly silence, and Juliska’s portrait seemed to stare at me like an apparition from behind the glass door of the cabinet. Her blue eyes, suddenly turbulent like the sea on a stormy night, inquisitively followed me around the room.

Overcome by exhaustion, I took a moment to rest in my armchair. I could hear water dripping in the bathroom – I knew this to be the tap with the worn-out rubber washer I kept reminding myself to replace – which was when it occurred to me that if there is one thing that I dislike in people, it is inconsistency, when they head in one direction in their aspirations but then retreat to old habits out of sheer laziness.

I once swore that I would not be that kind of person; on the fateful day of my encounter with my grandfather’s violin following the dress rehearsal of Turandot, I listened to a voice within, followed a sign. I believed in signs. I believed in an idea. I vowed that I would remain true to that idea and follow in my grandfather’s footsteps, perhaps become a member of the Opera orchestra or even go a step further and compose something of my own one day. An idea, however, is never born at our own command but chooses to wait for fertile ground – a moment when we are so susceptible to it that we would sacrifice everything for its sake; then it launches into the air like a hurricane, pulling everything else along in its wake.

For this reason, by believing in the abovementioned idea, I was also obliged to hold on to other beliefs which, instead of facilitating the fruition of my original idea, ended up being an aggravating factor. I believed that I could redeem myself for my past mistakes by eradicating not only the visible remnants of my past life which I so persistently wore – the red hair, earrings and T-shirts with provocative writing – but also everything else that I once zealously represented. I believed it to be my duty to honour Juliska by remaining eternally faithful to her and that I could easily obliterate from my mind my last encounter with Noémi with a change in attitude and an unwavering decision. I believed in the necessity of sacrifice for the sake of a higher artistic goal, in the vow of celibacy, in suffering as a solitary act.

Feeling utterly powerless, I let my head drop to my chest, when I suddenly caught sight of the white linen handkerchief, the corner of which was barely visible on the floor beneath the armchair. It must have fallen out of my pocket when I returned home in a frenzy following the failed attempt to return it to the Birdman a few days earlier. I picked it up, and as I held it in my hand the images of recent occurrences came flashing through my mind … the skulls on the two plastic bottles, the fixed grin of the obliging woman at the grocer’s, the red numbers, the Roma child in nappies, the delicate skin of Noémi’s thighs … At first I was unable to comprehend how all these events were connected, as if for some reason I lacked the ability to observe the picture as a whole. The one thing I was sure of, however, was that they had managed to fog the image of Juliska and place her on the sidelines of my life. And something was also telling me that these were events over which – even though I was the main protagonist – I did not have much influence.

I spent a moment or so pondering the word influence and began to realize something that had been right in front of my eyes but that I had been too distraught to recognize: that all those events or fragments of events could, in one way or another, be traced back to one central figure – to him. This uninvited revelation made my blood run cold, for it all suddenly started to resemble the work of the devil himself.

My situation at the time was unenviable, to say the least. However, the weight on my heart was gradually lifted in the days to come, for I was finally beginning to understand that my visit to Noémi’s was not my own choice but rather the choice of that evildoer who seemed to have led me to her by use of some mysterious force. This realization, incidentally, was a crucial element of my theory about the true intentions of that man – a theory that I developed shortly after and that I will refer to frequently in the pages to follow because it had marked the moment when I began to regard him as the sole source of all my woes.

____________________________________________________________________

DANA TODOROVIĆ is a novelist and translator living in Belgrade. She is half-Serbian, half-American, and although she was educated mainly in the US and UK, she prefers to write in Serbian. Her debut novel, Tragična sudbina Morica Tota (The Tragic Fate of Moritz Toth) was shortlisted for the Branko Ćopić prize for best novel, awarded annually by the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, and was also listed as one of the top novels of the year by the NIN weekly and the daily Politika. Her second novel Park Logovskoj was shortlisted for several major literary awards, including the prestigious NIN award. Both novels were also published in Germany. In addition, she is the author of two children’s books, as well as several short stories that have appeared in various magazines and anthologies.

The Tragic Fate of Moritz Toth is being published by Istros Books and Peter Owen Publishers in October 2017.

____________________________________________________________________

Read more from Serbian Fiction Week:

Fear and his Servant by Mirjana Novaković